Introduction

European competition law enforcement in the digital economy reveals a strong, yet healthy, tension. On one hand, administrative agencies, both at the European Union (E.U.) and national levels, began enforcing competition laws in digital markets with an increasingly precautionary approach. On the other hand, courts reacted by significantly restraining these interventions, reinstating the basic legal principles and economic rationales widely accepted for enforcing competition laws in any sector of the economy. In this chapter, I explore this tension by outlining the precautionary approach adopted by European administrative practice whilst referring to the safeguards and limits enforced by the judiciary.

European administrative agencies first adopted a “precautionary approach” in their enforcement decisions because it aligned with the well-known “precautionary principle.” The precautionary principle is a general principle of law,[1] used as a decision-making tool to address scientific uncertainties.[2] Referred to as “a magic spell” principle[3] encouraging “obscurantism,”[4] the precautionary principle originates in a fear of a future health, environmental, or social catastrophe. Described as “Ill-defined,” the principle enjoys a “philosophical reputation [which] is low.”[5]

As a regulatory tool, the precautionary principle is defined by the following core elements: (i)Uncertainty: it is applicable to inform a decision when there is a lack of scientific certainties and/or of full knowledge; (ii) Lack of harm: actual harm, or even foreseeable harm, is not required—only the potential of a future harm (i.e., a hypothetical harm,)[6] is necessary for the precautionary principle to apply; (iii) Shift of the burden of proof: the private actor must prove to the regulator an absence of negative effects and/or efficiencies deriving from its business conduct, harm is assumed unless proven otherwise; and (iv) Urgency to regulate: the irreversibility of the damage envisaged, together with the inability of the private actor to demonstrate an absence of negative effects and/or efficiencies justifies immediate regulation through interim and/or permanent measures.

When these elements are identified, the precautionary principle is successfully invoked by regulators, enforcers, and market players as a justification for intervention. By placing a high burden on the market participant to prove an absence of negative effects and/or efficiencies associated with normal business conduct, and mandating regulation in the absence of evidenced market failures, the precautionary principle stifles innovation.[7]

Essentially, the precautionary principle “lowers the evidentiary bar for policy-making on risks”[8] and can trigger “false alarms”[9] generating false positives, fostering over-regulation which in turn deters innovation. In fact, the precautionary principle paralyzes innovation[10] and instills fears.[11] The principle has been extensively broadened by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in the context of hazardous activities, environmental protection, and other issues involving serious health threats.[12] In this context, the ECJ suggested that public authorities may be compelled to actively enforce the precautionary principle whenever they make decisions.[13] The ECJ interpreted the precautionary principle as obliging public authorities to prohibit activities with the potential to affect the integrity of a natural site, thereby recommending de facto prohibitions of these types of activities or projects.[14] Finally, the ECJ considered that a probable causality between the activity envisaged and the hypothetical risks considered, was sufficient for the application of the precautionary principle in preventing or prohibiting the activity.[15]

While the application of this principle in areas involving serious risks to health at first glance seemed justified, it nevertheless resulted in prohibiting innocuous activities in the absence of evidence of potential harm. The extensive interpretation by the ECJ and later its adoption by public authorities resulted in the creation of an extensive ex-ante interventionist tool.

Moreover, despite early forecasts that the precautionary principle would “risk international isolation” as “controversial and ill-understood,”[16] the precautionary principle now enjoys full recognition and widespread enforcement in any European regulatory intervention.

The core elements of the precautionary principle have permeated into European competition enforcement and now have a predominant role in its application to the digital economy. This is reflected both in recent enforcement decisions and regulatory proposals under public consultation.[17]

In Section I of this paper, I examine the origins or seeds of precautionary antitrust by revisiting enforcement by European administrative competition agencies in digital markets. In Section II, I explain how this ideology was embraced, advocated, and advanced in several “tech reports” representing the blossoming of the precautionary principle. I conclude in Section III, by proposing the reinstatement and further development of tools that protect the legal and economic rationale of antitrust, as recognized by European courts.

I. Seeds of Precautionary Antitrust: European Competition Enforcement

The European Commission’s (Commission) recent digital platform decisions provide both the seeds and the “evidence” to which the multiple digital reports and legal reform advocates refer when advocating for precautionary antitrust enforcement. I demonstrate in this chapter, that far from identifying harm under the consumer welfare standard, the decisions show a systematic erosion of well accepted legal and economic principles which are the basis of European competition policy and enforcement. The evolution of the Commission’s decision practice shows a move from an effects-based approach towards formalistic structural presumptions. Nevertheless, the Courts (i.e. the General Court and the ECJ) provide the necessary judicial checks to ensure adherence to rule of law principles and sound economic reasoning[18]. After illustrating the core elements of the precautionary approach towards the digital economy in the European decisional practice, I show the role of the Courts to safeguard rule of law principles and the traditional economic analysis that modernized antitrust enforcement.

Recent Commission decisions on the digital economy are fraught with examples of the application of each of the principles of precautionary antitrust.

First, antitrust enforcement towards digital players is replete with incommensurable uncertainties. Both the literature[19] and agency digital reports[20] acknowledge the obvious fact that traditional antitrust enforcement is massively challenged by disruptive technologies with novel characteristics such as two-sided markets, zero-priced markets, ecosystem-building via new business models, etc. European decisional practice recognizes these difficulties and emphasizes the inherent risks of intervening in an area where innovation incentives are essential to the benefits of the digital economy and consumers.[21]

Second, the Commission’s enforcement also reveals ignorance regarding some technical aspects of the businesses under its review. This is illustrated, for example, by the Commission decision in the Facebook/WhatsApp merger,[22] extensively cited as an example of failure of the E.U. Merger Regulation (EUMR) to prevent anticompetitive mergers.[23] The Commission found WhatsApp and Facebook were not close competitors in the market for consumer communication because consumers used both applications on the same device, and one service required the creation of a profile while the other was accessed via phone number. However, the Commission later on realized it was technically possible, at the time of the merger, to match Facebook and WhatsApp users accounts and fined Facebook for providing misleading information.[24] The merger was therefore cleared on the basis of unverified information showing an evident need to increase competition authorities’ know how of the industry.

Third, European enforcement has increasingly reneged on the requirement to identify harm to consumers to find antitrust liability. The theory of harm has morphed into a theory of choice.[25] This evolution started with a lowering of the threshold to a requirement of potential harm,[26] as opposed to actual proof of harm. It then openly embraced the protection of consumer choice.[27] Along the Ordoliberal tradition,[28] and to avoid “market tipping”[29] in digital markets, the reduction of consumer choice functioned as a substitute for evidence of consumer harm. This created a bias against big companies in favor of small companies.[30] This precautionary approach places a blind faith in structural presumptions and assumes, without analyzing market dynamics, that innovation and economic benefits will necessarily be greater in a market with a larger number of small (potentially less efficient) firms than in one with a few large firms. The underlying principle is the purported need to preserve consumer choice to preserve competition. Consumer choice is further pursued through the downgrading of the role of market definition in lieu of effects analysis (leading to narrow ad hoc market definitions fitting the purported theories of harm);[31] the introduction of novel dominance concepts (such as “intermediary power”); and the prima facie condemnation of normal or competitively neutral business practices (such as “self-preferencing”).[32]

The predominance of consumer choice as a substitute for consumer harm is evidenced by the Google Shopping decision. In June 2017, the Commission fined Google €2.42 billion for infringing Article 102 TFEU by allegedly leveraging its market dominance as a search engine to gain an illegal advantage in the market for comparison-shopping.[33] Although the reasoning and facts indicate the theory of harm was discrimination,[34] the Commission framed it under the novel theory of “abusive leverage.” Whether European Courts will accept this theory has yet to be determined, and is a subject in the pending appeal.[35] However, the decision as it stands today, clearly departs from the decisions of other competition authorities, including the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC), several U.S. State Attorneys General, and Canada, all of which have closed investigations into Google based on theories of “self-preferencing“ and “self-bias.”[36]

Google’s search engine originally produced ‘generic or horizontal’ search results, but has evolved to provide ‘specific or vertical’ search results in the form of sponsored ads and links (featured at the top of the page), and commercial products, services, and information (generally included in separate boxes). The combination of horizontal and vertical search has been referred to as “Universal” search. Thus, when a search is entered, three separate sets of results are exhibited, two of which lead to Google affiliated services. Google has also added additional services, including the comparison-shopping business (which also appears in an upper box).[37] According to the Commission, the comparison-shopping business was initially unsuccessful until Google began to employ a new business strategy.[38] The strategy consisted in prominently placing its own comparison-shopping service at the top of Google’s search results.[39] The Commission found two relevant product markets: one for search services (where Google had a 90% market share), and a separate market for comparison shopping services.[40] The Commission concluded that the relevant geographic market was national in scope.[41] The Commission found Google was dominant in the national markets for general search in the EEA (with the exception of Croatia), since 2011.[42]

The Commission essentially found Google’s self-favoring conduct was anticompetitive because it diverted traffic away from competing services to its own; and was capable or likely to have anti-competitive effects in the markets for comparison shopping and general search.[43] The Commission found the anticompetitive effects were a potential foreclosure of competing comparison-shopping services (potentially leading to higher fees for merchants, higher prices for consumers, and less innovation) and a likelihood of reducing consumers’ access to the most relevant comparison-shopping services. The Commission also found Google failed to provide evidence of efficiencies.[44]

The diversion of traffic was achieved by submitting competing offerings only to the generic search ranking algorithm, and reserving the best positioning in the generic search results and the separate boxes (which included pictures and graphics) for Google’s own offerings. According to the Commission, this conduct alone was sufficient to make a claim for “abusive leveraging” creating a new category of infringement to Article 102 consistent with self-favoring.

The Commission’s analysis was focused on “discrimination” i.e. that the placement of Google’s products was not a result of the algorithm but instead that they received different treatment. Rather than provide a showing that specific competitors were excluded, or that a percentage of the market was foreclosed to them, the decision proposed that a plausible gradual foreclosure in the longer term was sufficient to find an infringement.[45] The decision also failed to provide evidence of consumer harm and relied on statistical analysis of visibility and other metrics related to the presentation and display of unaffiliated shopping sites between 2010 and 2016.[46] Clearly focused on consumer choice, the Commission prioritized the availability of short term options and disregarded the consumer welfare effects of the innovation of “new search result boxes.”[47] Therefore, the Commission’s theory of harm is elusive and unconvincing.

Along the same lines, in the Google Android decision, the Commission sent a second infringement decision to Google in July 2018, with a fine of €4.34 billion for allegedly breaching Article 102 TFEU by imposing illegal restrictions on Android device manufacturers and mobile operators.[48] While the Commission adopted more generally accepted theories of harm, such as tying and exclusivity, the case was built on an extremely narrow market definition that disregarded competition between Android and Apple devices. It was also based on the proposition that Google used its dominance in one market to benefit another market where it was also dominant.

The Google Android Decision defined four relevant product markets: (i) the worldwide market (excluding China) for the licensing of smart mobile operating systems (OSs); (ii) the worldwide market (excluding China) for Android app stores; (iii) the national markets for general search services; and (iv) the worldwide market for non OS-specific mobile web browsers. The decision considers Google dominant in the first four markets.[49]

The Commission found Google had: (i) tied the Google Search app and Google Chrome browser with the Play Store; (ii) made exclusivity payments to large manufacturers and mobile network operators conditioned on the pre-installing of the Google Search app; and (iii) conditioned licensing, obstructing the development and distribution of competing Android systems (Android forks). The Commission found these constituted a “single and continuous infringement” aimed at transferring Google Search’s market power from desktop to mobile devices. As part of this strategy Google bought the original developer of the Android mobile operating system and continued to develop Android, which, according to the Commission, now accounts for 80% of the smart mobile devices in Europe and worldwide. Surprisingly, the Commission’s theory of harm proposes Google used its market dominance in the Play Store to leverage its power into the search market where it is also dominant.[50] Even more puzzling is the fact that no separate market is defined for search on desktop and mobile devices.[51]

Moreover, the Commission should not have excluded the main incumbent, Apple, from smart mobile operating systems simply because Apple does not license its OS. Instead, the Commission should have defined the market as the market for smart mobile operating systems.[52] This alternative market definition is supported by the fact that Apple and Android devices compete at the consumer level.[53] The Commission discarded consumer level competition between Apple and Android devices, claiming it was insufficient based on a series of factors consumers consider when choosing a device including their different prices, branding, and switching costs. However, these factors are elements of inter brand competition not only between devices but between operating systems. Finally, the underlying theory of the case seems to be that Google apps or the Google licensed version of the Android are “essential” or “must have” for device manufacturers, i.e. that they constitute an “essential facility.”[54] The Commission, however, does not present this theory of harm nor provide evidence of a refusal to supply that would support it.

More importantly, the effect of the Google Shopping and Google Android decisions seems to reduce rather than increase welfare. The bundling of the Google Play Store, Google Search app, and Google Chrome browser funded the free Android OS through the advertisement revenue from Google Search either in the Search app or Chrome browser.[55] By requiring the unbundling of these services, the Commission disrupted the business model and Google has announced it will charge for licensing the apps for Android including the Play Store.[56] End-consumers appear to be harmed by this decision while the theory of harm seems fragile.

Finally, on March 2019, the Commission issued a third decision against Google fining it €1.49 billion for an alleged infringement of Article 102 TFEU by imposing contractual restrictions on third-party websites to cement its dominance in the market for intermediation of online search advertisements (Google AdSense Decision).[57] AdSense works as an online search advertising intermediation platform, connecting owners of “publisher” websites with search functions (newspapers, travel sites, etc.) that want to profit from the space around their search results, with businesses that want those advertisement spaces.[58]

The Commission defined the relevant market as “online search advertising intermediation” in the EEA where Google had a market share above 70% (2006-2016).[59] The Commission also found Google had shares generally above 90% in the national online markets for general search and above 75% in most of the national markets for online search advertising.[60]

The alleged anticompetitive conduct consisted of: (i) entering into contracts with exclusivity clauses prohibiting third party websites from including search advertisements from competitors in 2006; (ii) later in 2009, replacing the exclusivity clauses with “Premium Placement” clauses reserving the most profitable space and a minimum amount of Google ads; and (iii) in 2009 requiring written approval from Google prior to any changes in the way rival ads are displayed.[61] The Commission argued these practices covered over half of the market (by turnover) and that Google’s rivals were not able to compete on the merits.[62] The Commission further proposed that, since other competitors in online search advertising, such as Microsoft and Yahoo, cannot sell advertising space in Google, third party websites represent an important entry point for these companies to grow and compete with Google.[63] The Commission’s theory seems to imply that these contractual measures are able to foreclose Microsoft and Yahoo, without providing much evidence of the likelihood of that happening. In brief, the Commission argues that:

Google’s rivals [Microsoft and Yahoo] were unable to grow and offer alternative online search advertising intermediation services to those of Google. As a result, owners of websites had limited options for monetizing space on these websites and were forced to rely almost solely on Google.[64]

While the decision seems focused on classic theories of exclusion, it is likely the full text includes “essential facilities” reasoning based on the relevance of Google as an “intermediary” of these services. Because the Commission seems interested in defending a wider availability of advertisements, the question of whether this results in more benefits to consumers arises, as well as how to determine and measure harm.

The precautionary approach also shifts the burden of proof in antitrust analysis. The digital reports epitomize several proposals where the defendants (or the merging entity) would bear the burden of proving the harmlessness of their business conducts. [65]

The Commission has continued to deepen its concern for the role of digital platforms as “intermediaries” and to observe self-preferencing or self-favoring conduct with suspicion. In July 2019, it opened an investigation into Amazon based chiefly on the company’s role as both a seller of products on its platform, and as the provider of a marketplace where other companies, including competitors, sell their products to consumers (Amazon Investigation).[66] This alleged “conflict of interest” between Amazon-as-platform and Amazon-as-retailer inverts the burden of proof onto Amazon to demonstrate the absence of anticompetitive consequences of its dual role. Specifically, the Commission is concerned Amazon may use competitively sensitive information about other sellers, their products, and transactions to gain a competitive advantage.[67] The investigation will look into: (i) standard agreements between Amazon and marketplace sellers that allegedly allow Amazon to analyze and use third party seller data and how that may affect competition; and (ii) the role of data in the selection of the winners of the “Buy Box” and the impact of Amazon’s potential use of competitively sensitive marketplace seller information on that selection.[68]

The Amazon investigation, therefore, seems to echo and reaffirm the concerns of the Google Shopping Decision: that the platform itself constitutes a relevant market, making the company a monopoly by default, and that the “dominant” platform must grant equal treatment within its proprietary technology to clients and competitors.

Additionally, this proposition is directly at odds with Commissioner Vestager’s remarks that European consumers have benefited from online shopping because “E-commerce has boosted retail competition and brought more choice and better prices.”[69] The Commission, therefore, states that online commerce competes and disciplines physical retail shopping, while at the same time proposing that one online distribution channel, i.e. sales through Amazon, constitute a separate relevant market.

Finally, the seeds of precautionary antitrust can be illustrated by European enforcement of interim measures. There is no precautionary principle without the ability to legitimately regulate before harm arises, based on hypothetical risks. In what is perhaps the clearest showing of precautionary antitrust enforcement, the Commission imposed interim measures for the first time in 20 years, and for the first time under Regulation 1/2003, on the U.S. company Broadcom.[70] A lack of evidenced harm or market failures does not prevent either regulatory or enforcement interventions. Broadcom was deemed prima facie dominant in certain chipset markets, and the Commission ordered it to stop its conduct, pending a final decision on the merits (Broadcom Decision).[71]

The Commission found Broadcom dominant in the worldwide markets for Systems-on-a-Chip (SoCs) for Front End Chips and Wi-Fi Chips for inclusion in: (i) TV set-top boxes (STBs); (ii) DSL residential gateways (RGs) and; (iii) and fiber RGs.[72] The alleged anticompetitive conduct concerned six “exclusivity inducing” provisions contained in agreements with original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) regarding SoCs for STBs and/or RGs. These provisions included so called “exclusivity or quasi-exclusivity agreements” and others deemed by the Commission as “leveraging Broadcom’s market power to other markets or products.”[73] The justification for the interim measures was the likelihood that Broadcom’s competitors would be increasingly marginalized or forced to exit the market before the Commission came to a final decision.[74] However, for the Broadcom Decision to stand under Article 8 or Regulation 1/2003, the Commission must meet the burden of showing: (i) risk of serious and irreparable damage to competition; (ii) on the basis of a prima facie finding of an infringement. The decision does not meet these standards and directly contravenes ECJ precedents such as Intel.[75]

Assuming arguendo that the Commission’s market definitions are true to market dynamics, and that Broadcom is dominant within those markets, the alleged conduct (i.e. exclusivity and loyalty rebates) is conduct analyzed according to its effects. As such, a prima facie finding of illegality changes the legal standard and the burden shifting regime under which this conduct is analyzed, turning them into restrictions by object and placing the burden on the defendant to show procompetitive efficiencies that outweigh the identified risks.

However, the effects of the interim measures extend far beyond an inversion of the burden of proof and legal standard, they operate as de facto condemnation. This is because the defendant will logically prefer to offer commitments rather than wait for a final decision which, likely, will restate the Commission’s interim findings. This was exactly the case here where Broadcom offered extensive commitments aimed at remedying the Commission’s preliminary findings of harm.[76]

While European decisional practice features the essential elements of the precautionary principle, thereby abandoning effects-based analysis in favor of a more deontological approach that relies on structural presumptions, the judiciary and especially the ECJ, have provided the necessary safeguards to ensure adherence to the rule of law and sound economic reasoning. This is exemplified by the 2017 Intel judgment[77] where the ECJ set aside a judgement of the General Court on the basis that the court failed to assess Intel’s effects arguments. The ECJ held the General Court failed to consider Intel’s arguments against the ‘as efficient competitor’ test in the Commission’s decision which fined Intel for having abused its dominant position via rebate schemes.[78] The ECJ held that economic arguments must be thoroughly reviewed by the General Court rather than assumed true as stated in the Commission’s decisions. This decision represents a strong blow to the Commission’s precautionary approach, which relies on mere hypothetical risks of effects. Indeed, rightly perceived as a revitalization of the “effects-based approach” in competition law[79] and more generally of the importance of economics in antitrust enforcement, the 2017 Intel judgement illustrates the recent direction adopted by the Court: more economic-based and aligned with traditional economic principles,[80] the Court clearly expresses its desire to judge by the facts and the economic evidence provided. This commonsensical judicial stance clashes with the less economic and more precautionary approach recently advocated by the Commission. Reversed burdens of proof rather than traditional evidentiary rules, new theories of harm rather than legally predictable infringements of competition laws, emphasis on hypothetical risks to the structure of competition rather than a requirement to evidence actual harm to consumers are contradictory stances between the Commission’s and the Court’s recent directions. Indeed, the ECJ’s requirement of actual effects removes the foundations of precautionary interventions since the economic approach (and evidence) are reinstated as essential to antitrust analysis. Economic intuitions cannot be accepted, the Intel judgment implied.[81] This limitation put a hold on what precautionary enforcers would like antitrust to become, when hypothetical risks of abuses of dominance are invoked without further economic evidence.[82] Consequently, it appears expectable that the ECJ will act in the near future as safeguarding economic principles (e.g. procedural and evidentiary rules, legal predictability, the importance of an economic approach over a structural approach) against the novel precautionary antitrust approach embraced by the European Commission and approved by the General Court.

In brief, the Commission’s enforcement matches the core elements of the precautionary principle. This position is at odds with an uncertain digital world where firms essentially compete for the market rather than in the market. In practice, big digital platforms seem to lack “the quiet life” of monopolies, they invest massively in research and innovation. Nevertheless, the perceived reduction of consumer choice and the winner-takes-all structure attributed to network effects is perceived by the Commission as a threat of irreversible competitive risk. The precautionary principle has therefore already taken significant strides into European competition enforcement. It is foreseeable that this unfortunate trend will continue to strengthen as the proposals contained in digital reports are implemented.

II. Digital Reports’ Proposals: The Blossoming of Precautionary Antitrust

The application of competition rules to digital markets and “multisided platforms” presents challenges for antitrust authorities because their business models depart from the traditional, one-sided markets prevalent when competition rules were designed. While there is consensus that competition rules are flexible enough to be enforced in the context of the digital economy,[83] calls to reform and reshape antitrust have emerged among competition agencies, think tanks, and politicians worldwide. The underlying premise for reform is that antitrust and competition policy has been unable to identify and remedy anticompetitive conduct in digital markets, and an alleged under-enforcement is the driving force supporting these calls for reform. The reflection by antitrust authorities of their role in digital markets started in 2018 and 2019 and materialized in a flurry of digital reports written or commissioned by the authorities.[84] The reports purport to give a better understanding of digital markets, identify market failures, and propose ex-ante regulatory or ex-post market interventions to address those market failures. This section analyzes the main proposals contained in the European digital reports, their presumptions, and underlying philosophy. What results is that the proposals epitomize a precautionary approach to antitrust enforcement in digital markets.

A. DG-Comp Report

The report commissioned by the European Commission’s Directorate General for Competition (DG-Comp Report): [85] (i) exhibits a hazardous inversion of the burden of proof, and a lowering of the standard of proof for conduct by large digital platforms; (ii) suggests the expansion of competition rules beyond consumer welfare objectives to encompass other public policy considerations; and (iii) calls for ex-ante market interventions through regulation. We find the DG-Comp Report calls for more vigorous antitrust enforcement and regulation, expressly recommends inverting the traditional error cost framework, and unduly embraces a precautionary approach.

The DG-Comp Report opens by announcing that strong economies of scope due to “extreme returns to scale”, “network externalities,” and the “role of big data” give large incumbents in digital markets a competitive advantage making them difficult to dislodge.[86] This conclusion is followed by a recognition that there is “little empirical evidence of the efficiency cost” produced by the difficulty of dislodging incumbents.[87] Despite this lack of evidence, the authors vouch for a “vigorous competition policy enforcement” by adjusting key aspects of EU competition rules.[88] The report concludes that there is no need to rethink the goals of competition policy, while proposing changes, that if adopted, would shift competition enforcement away from the consumer welfare standard and towards other social, political, and protectionist goals.

1. A Precautionary Shift of the Burden of Proof

In the DG-Comp Report, the consumer welfare standard is disregarded to the point that normal commercial practices employed by big platforms are forbidden despite the absence of consumer harm.[89] Big digital platforms are assumed “dominant” and may be found guilty unless they are able to prove their behavior creates efficiencies. This precautionary inversion of presumptions and the burden of proof weakens the rule of law as a matter of principle.[90] It also weakens the rule of law as matter of practice because the disparate treatment between allegedly dominant digital platforms and other dominant companies is arbitrary.[91]

Even more ambitiously, the DG-Comp Report recommends a radical change to the traditional and well accepted error cost framework[92] according to which false positives (i.e. wrongful convictions) are more costly than false negatives (i.e. wrongful absolutions) because self-correction mechanisms mitigate only false negatives[93] Not only is the burden of proof inverted (i.e. guilty until proven innocent), but the standard of proof is lowered (i.e. guilty for previously minimal or unproven harm).[94] This two-pronged relaxation of the traditional theory of harm reflects a bias towards false positives in digital markets despite the abundant evidence of the negative impacts of false positives.[95]

By placing the burden of proof on the allegedly dominant firm to justify normal commercial practices, the recommended measures protect competitors rather than competition.[96] The recommendations include mandating data portability and interoperability to allow for multihoming, switching, and the provision of complementary services within the platform.[97] The authors state that if the platform meets the “essential facilities” threshold, platforms must not engage in self-preferencing.[98] Further, even below this threshold, the authors suggest that self-preferencing by “dominant” platforms should be anticompetitive in the absence of a procompetitive justification.[99] Finally, self-preferencing, seems to be reprehensible only when done by platforms, disregarding that it is a normal commercial practice by vertically integrated firms.

Importantly, the authors label large platforms as ‘regulators’ of the interactions[100] that occur in their platforms when the platforms have adopted ‘pervasive rules’ regarding: (i) design; (ii) their relation with consumers; and (iii) interactions between users. [101] The authors consider that given this “rule-setting” element, platforms should be scrutinized with no lesser a standard than the one developed under Article 101 TFEU, thereby applying the “by object” standard of collusive practices to potential abuses of dominance which are analyzed according to their “effects”.[102]

Finally, the authors suggest revisiting substantive theories of harm for mergers to address concerns stemming from the acquisition by a dominant company of a “target with low turnover but a larger and/or fast-growing user base and high future market potential”.[103] The report frames its concerns in what they describe as a “circumscribed set of circumstances” in a market with a “high degree of concentration and high barriers to entry, resulting, inter alia, from strong positive network effects, possibly reinforced by data-driven feedback loops.”[104] For such cases, the acquisition of a startup may “reduce the prospect of independent decentralized innovation.”[105] While the report expressly states tech acquisitions are not “killer acquisitions,”[106] it implicitly attributes the mentioned set of circumstances by default to any large digital platform.[107] The report invites suspicion towards virtually any acquisition by a digital platform, regardless of the financial benefit conferred to the sellers of the startup (and its effect on innovation) or the increase in consumer welfare, under the premise that they impede entry.[108] This presumption ignores both the possible procompetitive effects of mergers as well as competition between platforms. The explicit goal of scrutinizing and/or blocking these transactions and analyzing them under this presumption is to “minimize ‘false negatives.’”[109] With a suggestion to alter the theory of consumer harm, the burden would then fall on the notifying parties to provide evidence of offsetting merger-specific efficiencies for the acquired “nascent” technology which, by definition, has yet to deliver market efficiencies.

2. Widening the Scope of Competition Rules

The DG-Comp Report calls for giving less weight to market definition, in lieu of anticompetitive effects and theories of harm.[110] At the same time, the authors propose the adoption of “ecosystem-specific aftermarkets”[111] where the platform’s proprietary ecosystem is considered to be the relevant market. This automatically makes firms a monopoly of their proprietary services.[112] Replacing market definition with the proposed “ecosystem” definition implicitly suggests that market definitions should be drawn to fit newer theories of (undocumented) harm.

The report recommends market power be assessed in the context of behavioral economics and within the tailor-made concept of “unavoidable trading partner” or “intermediation power” seemingly applicable only to digital companies.[113] This proposal directly invites confusion between competition and consumer protection policy.[114] While consumer protection is aimed at preventing deception, unfairness, and consumer choice in individual transactions; competition laws promote economic efficiency and long-term consumer welfare.[115]

Further, the report posits the mere possession of data, unavailable to other competitors, is evidence of dominance, and the refusal to grant access or supply such data to competitors an abuse of the alleged dominance. This reveals a practice of prematurely condemning potentially procompetitive or competitively neutral practices[116] as well as a shift from an evidence based standard.[117] Importing consumer protection goals into antitrust analysis risks weakening competition policy by introducing public policy considerations and tradeoffs that depart from the consumer welfare standard and make it subject to the uncertainties of political decision-making. Both scholars and national competition courts have stressed that antitrust liability should not be extended to privacy violations, nor should an abuse of dominance be presumed merely because an allegedly dominant company infringes a privacy rule.[118]

The authors propose that data access and data interoperability can and should be mandated under Article 102 TFEU and applied to ‘competitively essential’ data, leaving the complex technical questions of what data meets this requirement for competition authorities to determine.[119] The authors further announce that because “ensuring a frictionless data interoperability on an ongoing basis” may surpass the capacity of competition authorities, sectoral regulation mandating data access and interoperability should be introduced.[120] By expressly proposing measures that are, by definition, regulatory (i.e. requiring technical expertise pertaining to sectoral regulators) under Article 102 TFEU, the authors advocate for a shift to ex-ante precautionary interventions in competition enforcement.[121]

The authors propose that competition law (as ex-post liability) must be seen as a “complement” to the regulatory framework, so that ex-ante regulations of the digital economy appear necessary to tackle the perceived market failures embodied by network effects.[122] The precautionary recommendations to intervene ex-ante overlook the positive effects of network externalities focusing only on negative outcomes.[123] Indeed, this recommendation assumes that network effects are market failures instead of market features, and thus they should be addressed through ex-ante interventions.[124]

Finally, the authors take a static approach and consider it equally important to protect competition on the market as competition for the market. [125] The authors argue “any practice aimed at protecting investment by a dominant platform should be limited and well-targeted.”[126] This unwarranted proposition justifies banning “wide” (i.e. no price differentiation between platforms) and “narrow” (i.e. no lower prices on sellers’ websites) most-favored nation (“pricing parity provisions” or “MFN”) clauses when platform competition is deemed “weak.” [127] This proposition seems to widely ignore that innovation markets are better understood under Schumpeterian dynamic efficiency where value is introduced by new products and processes.[128] This approach also discards prima facie the possibility that other sales channels may constitute substitutes to platform sales.[129] This approach also has the effect of inverting the traditional presumption, and treating vertical restraints as restrictions by object or, at least, as inherently suspect conduct.

Overall, the DG-Comp Report epitomizes underlying heightened suspicions towards digital platforms, especially those deemed “dominant” or which constitute an “unavoidable trading partner.” Most recommendations stem from the unfounded assertion that network effects in platforms result in monopolies or dominant companies benefiting from high barriers to entry due to switching costs.[130] This in turn invites the conclusion that “dominant” platforms have incentives to engage in anticompetitive behavior. To tackle these issues, the authors recommend a revolutionary U-turn from traditional legal and economic analysis of competition law: the law should be twisted so that the burden of proof is inverted[131] and the standard of proof is lowered.[132] This inversion and lowering of legal standards alter not only the procedural aspects of competition law, but more dramatically, substantive competition law.[133] Furthermore, it expands competition policy and enforcement to encompass the subject matter of sectoral regulations, such as e.g. data access, interoperability and portability, which are portrayed as a new form of abuse under Article 102 TFEU.

Importantly, the report calls for severely questioning the well accepted consumer welfare standard and principles of antitrust economics in the context of digital markets. Not only is evidence of consumer harm no longer required (or “documented”) to sanction business conduct,[134] but the implicit requirement of protecting competitors’ entry would de facto apply essential facilities doctrine to key platforms or important ecosystems. Both legal and economic suggestions reveal an inept cautionary tale calling for precautionary ex-ante and ex-post interventions tailormade for digital markets. The Commission has embraced this concerning view in its subsequent thinking and practice.[135]

B. The UK Furman Report

The report Commissioned by the UK Chancellor the Exchequer and Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (the Furman Report)[136] is the work of an expert panel tasked with considering potential competition opportunities and challenges brought by the digital economy and potentially recommending necessary changes.[137] Specifically, the report considers (i) the emergence of a small number of large players in digital markets (such as social media, e-commerce, search, and advertisement); (ii) the appropriate approach to merger control and conduct investigations; (iii) opportunities to enhance competition, increase business innovation and expand consumer choice; and (iv) how to asses the consumer impact of “zero priced” services.”[138]

The Furman Report starts with the general assertion that competition for the market cannot be counted on, by itself, to solve the problems associated with “tipping markets” and “winner-takes-most” effects allegedly inherent in digital markets.[139] It also asserts that “potential dynamic costs of concentration outweigh any static benefits.”[140] These premises, for which no empirical evidence is presented, underline the report’s conclusions and recommendations.

The analysis of zero priced products/services is presented within different public policy objectives ranging from consumer protection to democracy.[141] While the authors acknowledge that competition happens in different sides of the market, some facing consumers, others facing advertisers, when identifying risks they pare them down to consumer protection issues such as data privacy. As such, the report lacks any analysis, whether theoretical or empirical, of the potential risks and efficiencies associated with zero priced services. The authors point out that “with more competition consumers would have given up less in terms of privacy or might even have been paid for their data.”[142] While it is fairly obvious that “zero priced” services do entail some form of consideration, whether it is consumer attention or data or any other,[143] that fact in and of itself does not inform whether that consideration is anticompetitive, i.e. exclusionary or, in very narrow circumstances, exploitative.[144] Moreover, the use of such hypothetical counterfactuals leads to uncertain alternative conclusions regarding an ideal market structure. The ideal counterfactual is even more stretched under the highly debated proposition that digital markets are highly concentrated, which in turn stems from the proposition that the proprietary ecosystem of the platform is the market, i.e. that they are monopolies by default. What results are proposals for tailor made prohibitions and regulations applicable only to Facebook, Google, Apple, Amazon, and Microsoft as dominant in the markets for social media, search services, mobile app downloads, and e-commerce respectively (with Microsoft providing some competition).[145]

The most emphatic proposal in the Furman Report is the creation of a “Digital Markets Unit.”[146] Following this recommendation, and the 2018-2019 Competition and Markets Authority’s (CMA) Annual Report,[147] the “Data, Technology and Analytics Unit” (DaTA) unit was launched in 2019. DaTA is dedicated to support the CMA’s understanding of data and algorithms, materializing the authors’ Strategic Recommendation D, to monitor potential anticompetitive conduct in machine learning and in artificial intelligence.[148]

Interestingly, the Furman Report recommends establishing a “code of competitive conduct” applicable to only certain companies.[149] Seemingly a soft law instrument, this conduct code would create an unleveled playing field by apparently applying only to one industry or sector, i.e. digital companies, and regulating only “particularly powerful companies.”[150] The targeted regulatory intervention would be aimed at addressing companies with “strategic market status.” This notion, which resembles the DG-Comp Report’s notion of “unavoidable trading partner”[151] suggests a novel and highly controversial standard of dominance based on the role of platforms as intermediaries or “gatekeepers” in the market.[152]

On other aspects, the Furman Report calls for greater data mobility and systems with open standards to increase competition, consumer choice, and data openness. At the same time, it highlights the “Data Transfer Project” (DTP) initiated by Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft and Twitter who “believe portability and interoperability are central to innovation.”[153]

More perplexing is the emphasis on consumer choice rather than overall consumer welfare, despite declaring an adherence to the consumer welfare standard from which “there is no need to shift away (. . .).”[154] However, consumer choice is largely associated with the behavioral economics of consumer protection which are not in line and further contradict the consumer welfare standard.[155] In attempting to tackle both objectives, the Furman Report, like the DG-Comp Report, confuses and comingles competition policy (exclusively aimed at enhancing consumer welfare) with consumer protection policy (for which consumer choice can be an objective).

On merger review, the Furman Report recommends inverting the error cost framework in merger review not to err in favor of false negatives. This recommendation is based on the simple premise that “to date there have been no false positives in mergers involving major digital platforms because all of them have been permitted” while “it is likely some false negatives have occurred during this time.”[156] This is to say that simply because the CMA did not find any merger involving Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft, explicitly listed in the report to substantially lessen competition, the system necessarily is broken and must be fixed.[157] The proposed remedy includes both a shift in agency enforcement priorities as well as a legal amendment.[158]

The CMA would further prioritize the scrutiny of mergers in digital markets and closely consider harm to innovation and impacts on potential competition in its case selection and assessment. Digital companies deemed to have a “strategic market status” would be required to notify the CMA of all intended acquisitions. This default notification system applicable solely to the five mentioned companies would de facto enforce a presumption of illegality for any acquisition, regardless of their entity and/or structure (i.e. vertical, horizontal, or conglomerate). This proposal not only creates an uneven playing field with other firms not deemed to enjoy a “strategic market status,” but it advocates for a turn back to largely abandoned structural presumptions[159] and to depart from the economics-based approach embraced by the Commission after the 2004 modernization reform.[160]

The Furman Report states the merger control system should be amended. Although the authors openly claim that “the goal of the policy changes is not more or less enforcement but better enforcement,”[161] they paradoxically propose “there has been underenforcement of digital mergers, both in the UK and globally. Remedying this underenforcement is not just a matter of greater focus by the enforcer, as it will also need to be assisted by legislative change.”[162]

On a precautionary approach similar to the DG-Comp Report but even more pervasive, the Furman Report invites a greater use of interim measures as appropriate ex-ante regulatory tools for antitrust enforcement.[163] Justified on the grounds of risks of underenforcement and the risks of irreversible harm to competition, interim measures would be adequate when “antitrust cases may take years to resolve.”[164] In a surprising departure from principles of due process, procedural fairness, and the rule of law, the Furman Report identifies an “undue delay” inherent in appeals processes as well as risks of underenforcement as reasons for “focusing appeals” on limited grounds for judicial review.[165] Even ignoring the blatant departure from procedural fairness principles, the argument regarding the risks of underenforcement is circular, because judicial proceedings are precisely aimed at ensuring enforcement is appropriate. As such, the argument contained in Recommended action 12 proposing that judicial review should be limited to prevent underenforcement is, at a minimum, unconvincing.[166] The rule of law and the breadth of judicial review can hardly be questioned for the sake of facilitating a greater use of interim measures and a hastening of enforcement.[167]

C. Franco-German Working Paper on Algorithms and Competition[168]

The joint study by the Autorité de la concurrence and the Bundeskartellamt (FR-DE Algorithm Study)[169] addresses the specific phenomenon of algorithm-driven companies and the impact of their business strategies for antitrust enforcement. While taking due note that algorithmic collusion has yet to materialize,[170] this joint study recommends reconsidering the current exclusion of parallel behavior from the scope of Art. 101 TFEU to catch algorithmic parallel behavior.[171] Responding to the precautionary request by Commissioner Vestager to ensure “antitrust compliance by design”[172] (i.e. meaning “pricing algorithms need to be built in a way that doesn’t allow them to collude”),[173] the joint study states “competition authorities want to encourage companies to take precautions” since “companies need to think about how they could ensure antitrust compliance when they use pricing algorithms.”[174]

This ex-ante approach creates incentives for companies to detrimentally err on the side of too much precaution. First, the use of algorithms is perceived as an element of market power. The study references the Google Shopping case restating that “the establishment of a fully-fledged general search engine requires significant investments in terms of time and resources,” in particular with regard to the “initial costs associated with the development of algorithms.” The degree of market power will depend on the scale/scope and on the availability of data deemed necessary for rivals to compete with the company owning the algorithm.[175] Second, the study suggests data ownership, in a context of a presumed lack of rivalry (understood in a static efficiency context, i.e. competition within the technology) increases entry barriers. Third, the study posits that the refusal to supply information relating to proprietary algorithms can be tantamount to an exclusionary abuse[176] under what is a de facto transposition of the essential facilities doctrine to the strategic use of algorithms.

D. The OECD Report on Multi-Sided Platforms[177]

With a sharp set of proposals grounded on a rigorous economic analysis of antitrust framework applied to multi-sided platforms, the OECD Report achieves both the objective of addressing wide-ranging issues whilst being accessible, but also of drawing sensible normative conclusions as a path forward for a more robust antitrust framework applied to multi-sided platforms.

The key message on exclusionary conduct is that it should not be assumed to be harmless simply on the basis that it is exercised in a two-sided market. If anything, platform markets may provide particularly fertile ground for exclusionary behavior and merit greater scrutiny.[178] The inquiry must explore the impact on rivals’ costs and the intensity of competition. Price cost tests should not be used in multi-sided markets and recoupment tests should be interpreted with care since recoupment may happen simultaneously.

On multi-sided platforms’ efficiencies, where cross-platform network effects are strong, mergers of multi-sided platforms might be expected to generate efficiencies if they combine separate user bases and increase interoperability. Agencies should consider the scope for efficiency defenses in multi-sided markets. Focusing analysis on the magnitude and merger specificity of such effects, rather than their existence may therefore provide better analytical value for agencies. Operationally there may be advantages to running the competitive effects and efficiencies assessments as a single effects’ assessment in those cases where the multi-sided nature of the market is undisputed.

The complexity of vertical restraints calls for specific attention by antitrust authorities because agreements in multi-sided markets may require more scrutiny from agencies than similar agreements in one-sided markets. When free riding poses a threat to the viability of the platform, there may be a significant scope for vertical restraints to generate efficiencies, although this may not be the case for other investments that might be viable as a result of the restraint. Noticeably, the report explicitly considers “the strong cross-platform network effects” by emphasizing that “users are likely to switch away from platforms if sellers choose to delist” from platforms imposing vertical restraints.[179] The Report wisely concludes advising agencies engage in empirical, evidenced-based antitrust analysis rather than rely on presumptions and theoretical frameworks to support ex-ante interventions.[180]

E. Proposal to Amend the German Competition Law

The Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) presented a proposal to amend German competition law, the GWB Digitalization Act.[181] Among its primary objectives are implementing the recommendations of two reports, Modernizing the Law on Abuse of Market Power[182] and Competition Law 4.0. The proposal includes the addition of the concept of “intermediary power” to the list of considerations relevant to the assessment of dominance;[183] an amendment of the definition of abuse of dominance to relax the requisite element of causality between a finding of abuse of dominance and alleged anticompetitive conduct; the addition of a section to account for companies “with outstanding cross-market importance for competition;[184] provisions that categorize refusal to grant access to data, networks or other infrastructure as an abuse of dominance (reinvigorating the essential facilities doctrine);[185] and provisions that facilitate interventions to prevent markets form “tipping”, i.e., the emergence of a dominant firm due to strong network effects.[186]

This draft bill obviously constitutes the boldest move towards a return to strong structural and formalistic presumptions, and the creation of a heightened tailor-made legal standard. This proposal represents a strong move towards more ex-ante, sector-specific antitrust interventions.

F. The G7 Common Understanding[187]

This very general document outlines the benefits of the digital economy on innovation and growth, proposes that the existing competition law frameworks are flexible enough, and highlights the importance of competition advocacy and impact assessment, and the need for international cooperation.

Because of its flexible analytical framework, fact-based analysis, cross-sector application and technology-neutral nature, competition law can effectively apply to digital markets and to harmful anticompetitive behaviors emerging in the digital economy.[188] Concerns have been raised about whether the accumulation of large amounts of data by platforms can create barriers to entry or market power, especially when data is difficult to replicate. A case-by case, evidence-based approach is essential to properly address the most challenging elements of competition analysis in digital markets. The G7 leaders classically consider that the:

aggregation of data, in some circumstances, may create barriers to entry or enhance market power, but it does not necessarily have such a tendency, and in some instances can be procompetitive. Competition enforcers can evaluate data concerns based on the individual facts of a case to assess whether a firm’s use of data benefits consumers or harms competition.[189]

Calling for both competition impact assessment of policies and for greater international cooperation in that area, the G7 leaders fail to provide specific guidelines and to outline general proposals given the breadth of antitrust divergences across the G7 competition authorities with respect to their analysis of the digital economy.

G. Belgian, Dutch, and Luxembourg Joint Memorandum

This memorandum summarizes the findings of several digital platform reports including those of the UK and EU.[190] It recommends that DG Comp commission an economic study on merger control in the digital sector that builds on previous studies and analyzes past merger decisions and transactions that were not caught by the thresholds. They would also study which type of mergers are caught under the jurisdictional thresholds that are not based on turnover, such as transaction-value based thresholds. For the acquisitions that were not subject to review by competition authorities (e.g, because the turnover threshold was not exceeded), whether plausible theories of harm, such as the ones proposed by the DG Comp Report, or efficiencies have developed. For the acquisitions reviewed by competition authorities, they would determine if competition authorities had access to sufficient information to investigate the relevant theories of harm and efficiencies. Based on their analysis, the authors would discuss policy options designed to address an alleged under enforcement of competition rules in the digital sector.

Further, the memorandum recommends competition authorities develop the ability and willingness to offer ex-ante guidance on specific issues. Competition authorities need to develop a case-by-case approach that would allow DG Comp and NCAs to have a less formal fast track commitment procedure as a development of the practice under Regulation 1/2003 or in line with the Notice on informal guidance. This constitutes an unattractive return to the system existing prior Regulation 1/2003, which was abandoned with the modernization of EU competition law.

Aligned with the Cremer and the Furman reports, the memorandum suggests introducing and reinvigorating ex-ante tools to prevent competition issues.[191] These tools would facilitate the imposition of remedies by DG Comp and NCAs on dominant companies to prevent potential competition issues, instead of relying on ex-post enforcement. This overtly precautionary approach seems unpreoccupied with erring on overenforcement even if it comes at the expense of deterring innovation.

H. Italian Regulatory Authorities Report

On 30 May 2017, the Italian Competition Authority (AGCM), the Communications Authority (AGCom), and the Data Protection Authority launched a joint inquiry to develop an understanding of the impact of Big Data on personal data protection, market regulation, consumer protection, and antitrust law. [192] In July 2019, AGCM, AGCom, and the Data Protection Authority reached a common view on how to tackle these issues. This common view is developed through guidelines and 11 policy recommendations.

The final document that will gather the three Authorities’ final reports is forthcoming. However, this preliminary inquiry already proposes the adoption of a new legal framework to address effective and transparent use of personal data. It identifies the emergence of new privacy and competition risks. Among these risks is the threat that the concentration of power—as a result of the commercial exploitation of data and algorithmic profiling—poses not only to the economy, but also to fundamental rights, competition, pluralism, and democracy.[193] By comingling competition and consumer protection policies, this assessment frames an unlimited number of public policy and political goals under antitrust, abandoning the consumer welfare standard and disregarding its importance.[194]

The Report recommends strengthening international cooperation for the governance of Big Data. The AGCM has been part of several joint working groups and cooperation initiatives with respect to a better understanding of digital markets.[195] The Report advocates for a reduction of information asymmetries between digital corporations (platforms) and their users (consumers and firms).[196] The authorities deem it necessary to identify the nature and ownership of the data prior to its processing.[197] In line with the GDPR, this measure aims to strengthen the level of data protection while remaining consistent with national cybersecurity strategies.

The authorities further consider that merger control regulation should be reformed to increase intervention.[198] This Regulation must grant authorities powers to examine mergers below notifying thresholds to address “killer acquisitions.” For that purpose, the report recommends the amendment of Article 6(1) of Law n. 287/90 to introduce an evaluation standard grounded on the SIEC criteria “substantial impediment to effective competition.”[199] Finally, the report outlines the need to facilitate data portability and data mobility between platforms through the adoption of open and interoperable standards through competition law enforcement.[200] This requirement potentially subjects digital platforms to compulsory data sharing regardless of their ability to affect output in a relevant market. Thus, a firm that poses no identifiable threat to competition could be forced to direct valuable resources to assisting less-efficient rivals.

I. Precautionary Antitrust in the Reports: A Summary

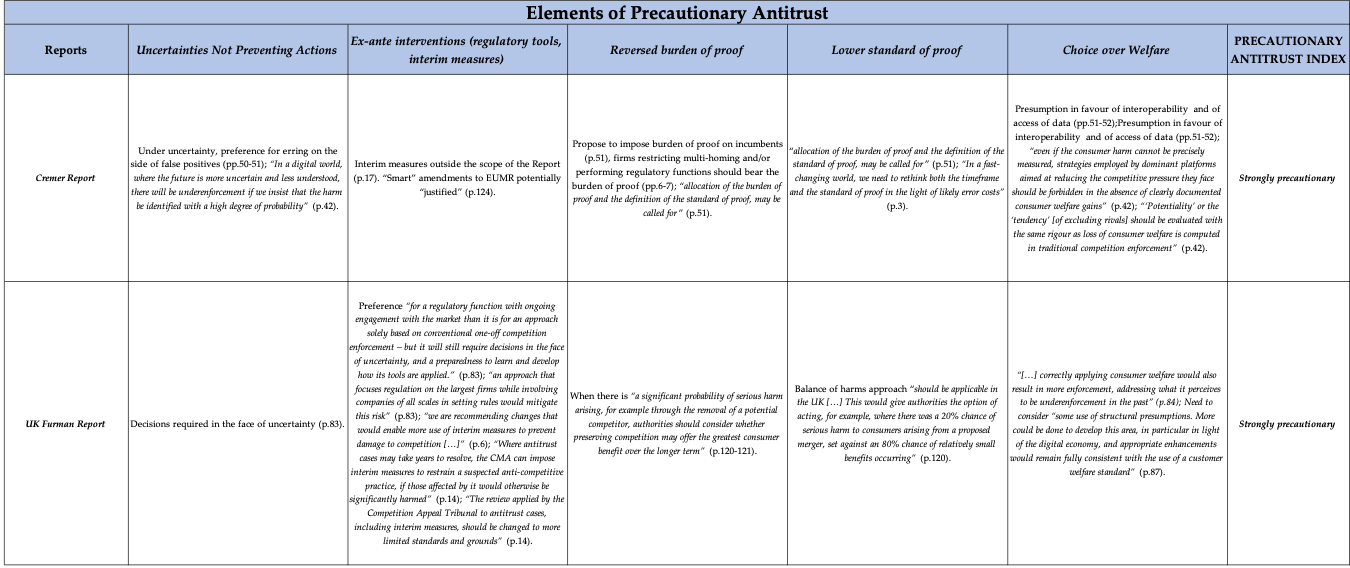

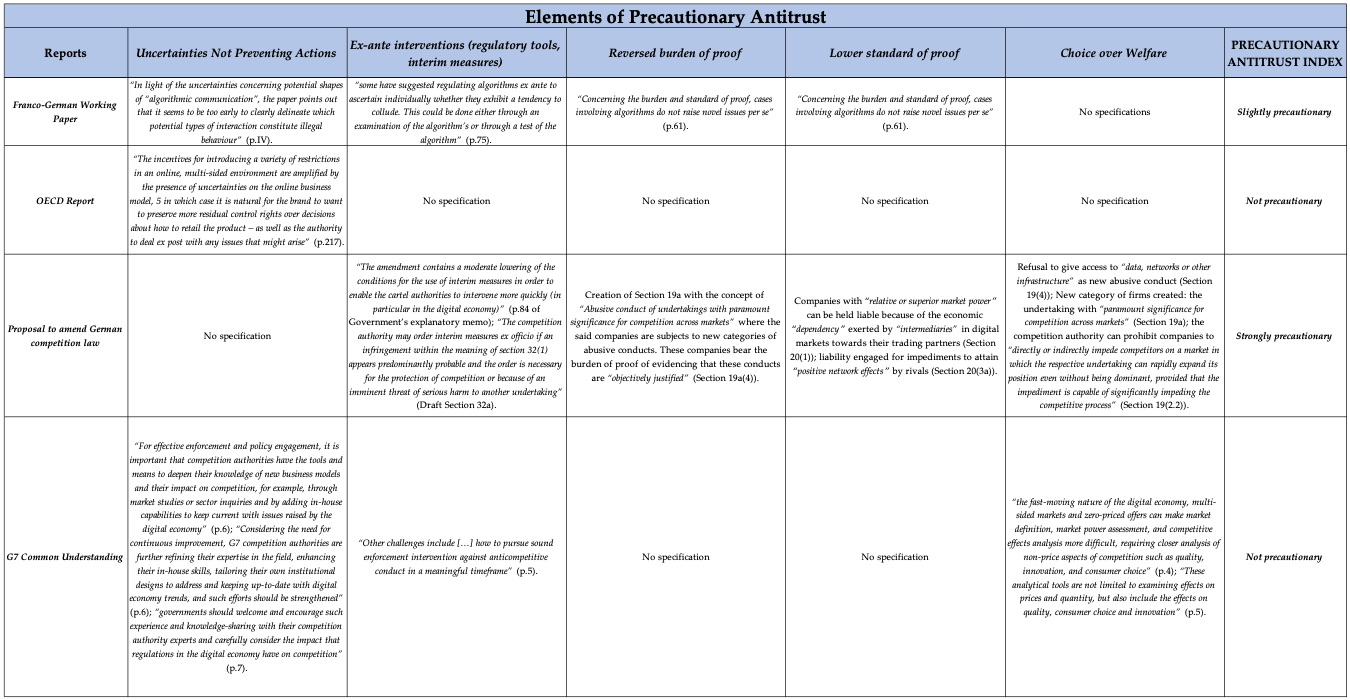

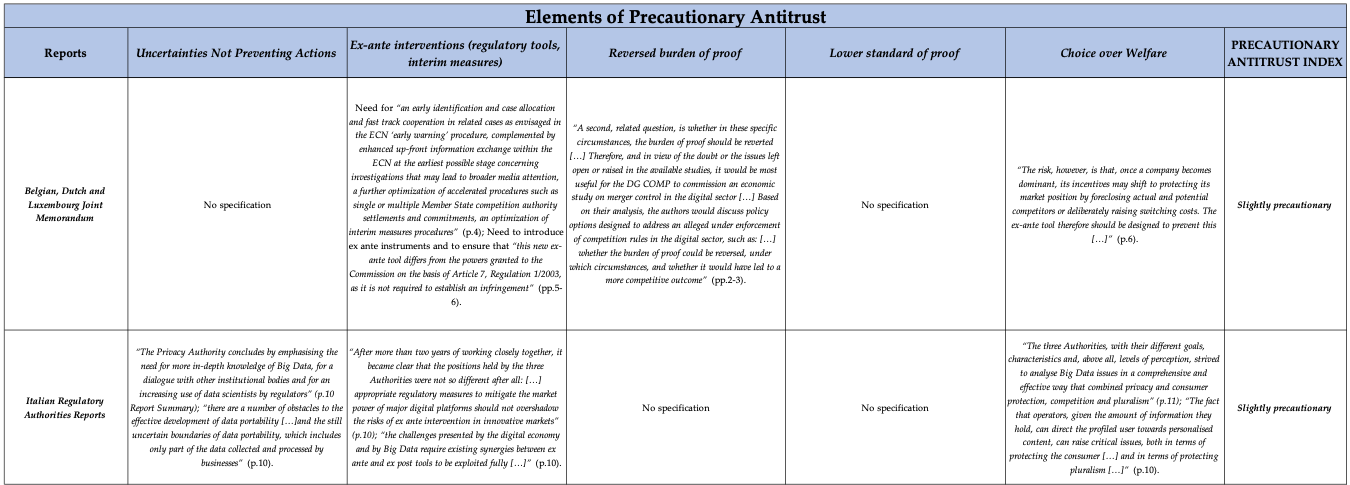

Competition enforcement towards digital markets reveals a precautionary approach by enforcers in the European Union. This trend is all the more exacerbated by the recent Digital Reports reviewed above. Some illustrations of how the elements of the precautionary principle have entered into antitrust proposals are sketched out in the table below. This table only partially portrays the precautionary perspective common to these reports. The most fundamental element may lay in the sceptical and mostly interventionist tone to be found in these reports. These reports all identify, more or less explicitly, a problem of under-enforcement which they use to justify the precautionary measures recommended in each of these reports. Consequently, these reports partake in the blossoming of precautionary antitrust in Europe, as made visible from the table below:

Conclusion: The Withering of Precautionary Antitrust

Precautionary antitrust, like the precautionary principle, has emerged in Europe out of a fear of irreversible damage by hypothetical risks, commanding urgent regulatory interventions. Precautionary antitrust begets regulation at the expense of innovation, it fosters the preservation of the status quo and deters new business models, disruptive strategies, and creative destruction. Precautionary measures in European antitrust are suggested, and both coincide with (and prove to be inspiration for) the U.S. Neo-Brandeisian perspective. These measures and reflections intend to paradigmatically alter the face of antitrust, from an ex-post antitrust liability, to part of a broader ex-ante regulatory framework that interacts with, and often overlaps with or confuses,[201] sectoral regulations.[202] The competitive process of innovation, dependent on the appropriability of the research being developed by platforms, is harmed in order to benefit smaller competitors. These smaller competitors get short term benefits through mandated measures that replace market competition (e.g. better ranking in search results, removal of vertical restraints imposed in exchange of freely provided services, data access without collection, interoperability without efforts to minimize switching costs, neutrality irrespectively of merits, etc.).

More importantly, the new competition tools proposed by the European Commission[203] strongly advocate for a shift from ex-post antitrust liability balancing pro and anti-competitive effects, towards ex-ante regulatory obligations akin to sectoral regulations. Should these types of initiatives materialize in Europe and abroad, the precautionary shift will radically change competition enforcement and the antitrust discipline as we understand it. Competition and antitrust are sound areas of the law precisely because their enforcement considers ex-post liability, is adjudicative, and is based in evidence and economics. Finally, the European shift towards precautionary antitrust will increase the innovation gap the European continent faces compared to the U.S.

Footnotes

[1] Aurelien Portuese & Julien Pillot, The Case for an Innovation Principle: A Comparative Law & Economics Analysis, 15 Manchester J. Int’l Econ. L. 214, 237 (2018).

[2] David Resnik, Is the Precautionary Principle Unscientific?, 34 Stud. Hist. & Phil. Sci. C Stud. Hist. Phil. Biological & Biomedical Sci. 329, 330 (2003).

[3] Philippe Kourilsky & Geneviève Viney, Le Principe de Précaution. Rapport au Premier Ministre, Odile Jacob, Documentation Française (1999), https://www.vie-publique.fr/sites/default/files/rapport

/pdf/004000402.pdf; see generally Per Sandin, Dimensions of the Precautionary Principle, 5 Hum. Ecological Risk Assessment : Int’l J. 889, 907 (1999).

[4] Claude Birraux & Jean-Ives Le Déaut, (2012) ‘L’Innovation à l’Épreuve des Peurs et des Risques’, Rapport déposé à L’Assemblée Nationale et au Sénat 183 (Office Parlementaire 2012)(describing the fear for innovation and the rise of the new obscurantism), http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/pdf/rap-off/i4214.pdf.

[5] Stephen M. Gardiner, A Core Precautionary Principle, 14 J. Pol. Phil. 33, 33 (2006).

[6] See generally, Stephen Charest, Bayesian Approaches to the Precautionary Principle, 12 Envtl. L. & Pol’y F. 265 (2002). See also Thibault Schrepel, Retooling Antitrust Law for Digital Markets, Le Concurrentialiste, https://leconcurrentialiste.com/antitrust-law-digital-markets/.

[7] Aurelien Portuese & Julien Pillot, The Case for an Innovation Principle: A Comparative Law & Economics Analysis, 15 Manchester J. Int’l Econ. L. 214, 237 (2018) (demonstrating the precautionary principle deters innovation and advocating for a principle that fosters innovation).

[8] Noelle Eckley & Henrik Selin, All talk, little action : precaution and European chemicals regulation, 11.1 J. Eur. Pub. Pol’y, 78, 82 (2004).

[9] Steffen Foss Hansen & Joel A. Tickner, The precautionary principle and false alarms – lessons learned 12 (EUR. Env’t Agency 2013) (identifying four instances where the precautionary principle has led to overregulation : “The analysis revealed four regulatory false positives : US swine flu, saccharin, food irradiation, and Southern leaf corn blight. Numerous important lessons can be learned from each, although there are few parallels between them in terms of when and why each risk was falsely believed to be real.”).

[10] See Caroline Orset, Innovation and the precautionary principle, 23 Econ. of Innovation and New Tech., 780, 797 (2014) (concluding “we have found that the consequences of precautionary regulation may be harmful for innovation. Indeed, some new activities may not be undertaken by the agent under regulation while it could have been done without regulation. Precautionary state regulation may then be paralyzing for innovation.”); Portuese & Pillot, supra note 7; Kathleen Garnett, Geert Van Calster & Leonie Reins, Towards an innovation principle: an industry trump or shortening the odds on environmental protection? 10 L., Innovation & Tech. 1, 14 (2018); European Risk Forum, The Innovation Principle: Overview (2013), http://www.riskforum.eu/uploads/2/5/7/1/25710097/innovation_principle_one_pager_5_march_2015.pdf; Eur. Comm’n, Towards an Innovation Principle Endorsed by Better Regulation, 14 (2016).

[11] Cass R. Sunstein, Laws of Fear : Beyond the Precautionary Principle (Cambridge University Press eds., 2012).

[12] See C-157/96 63, The Queen v Ministry of Agriculture 1998 ECR I-2211 64 ; C-180/96 99, United Kingdom v. Commission 1998 ECR I-2265 100.

[13] See T-13/99, Pfizer Animal Health v Council 2002 ECRII-3305 444; T-70/99, Alpharma v Council ECR 2002 II-3495 355.

[14] See C-127/02, Waddenvereniging & Vogelsbeschermingvereniging 2004 ECR I-7405 45.

[15] See C-280/02, Commission v France 2004 ECR I-8573 34.

[16] See Giandomenico Majone, What Price Safety? The Precautionary Principle and its Policy Implications, 40 J. Common Mkt. Stud. 89, 90 (2002).

[17] Not only is this precautionary approach to European competition enforcement visible in the Digital Reports (see Section II infra.), but it is advocated for in recent public consultations initiated by the European Commission. See e.g., Press Release, Antitrust: Commission consults stakeholders on a possible new competition tool (June 2, 2020), https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_977 (proposing the need for “a possible new competition tool to deal with structural competition problems across markets which cannot be tackled or addressed in the most effective manner on the basis of the current competition rules (e.g. preventing markets from tipping)”); See also Eur. Comm’n, Digital Service Act Package – Ex ante regulatory instrument of very large online platforms acting as gatekeepers, Roadmap (2020), https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives

/12418-Digital-Services-Act-package-ex-ante-regulatory-instrument-of-very-large-online-platforms-acting-as-gatekeepers (stating that the “impact assessment will examine different policy options for the effective ex ante regulatory framework that ensures that online platform ecosystems controlled by large online platforms that benefit from significant network effects remain fair and contestable, in particular in situations where such platforms may act as gatekeepers.”); See also Eur. Comm’n, Single Market – new complementary tool to strengthen competition enforcement, Roadmap (2020), https://ec.europa

.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12416-New-competition-tool (stating that “the initiative intends to address as specific objectives the structural competition problems that prevent markets from functioning properly and tilt the level playing field in favour of only a few market players. Restoring undistorted competition on these markets will deliver competitive outcomes in terms of lower prices and higher quality, as well as more choice and innovation to European consumers. It will also help small and medium-sized enterprises to compete more effectively against powerful incumbents and reap the fruits of their investments.”).

[18] This judicial safeguard requiring economic evidence and adhering to economic principles is mainly illustrated by the ECJ Intel judgment. See below at p.19 et sub.

[19] John M. Newman, Antitrust in Digital Markets, 72, 5 Vand. Law Rev. 1497, 1561 (2019) (noting from the onset that “antitrust law has largely failed to address the challenges posed by digital markets”); Antonio Capobianco & Anita Nyeso, Challenges for Competition Law Enforcement and Policy in the Digital Economy, 9 J.Eur. Competition L. & Prac. 19, 27 (2019); Dirk Auer & Nicolas Petit, Two-sided markets and the challenge of turning economic theory into antitrust policy 60(4) Antitrust Bull. 426, 461 (2015); Diane Coyle, Practical Competition Policy Implications of Digital Platforms, 82 Antitrust L. J. 835, 860 (2019) (concluding that “there is no settled approach either in the economic literature or competition practice to weighing static efficiency against the potentially much larger dynamic efficiency gains or losses”); Pablo Ibáñez Colomo, A Contribution to ‘Shaping Competition Policy in the Era of Digitisation’, 2 (Sept. 30, 2018) (unpublished manuscript); Daniel Crane, Ecosystem Competition and the Antitrust Laws, 98 Neb. L. Rev. 412, 424 (2019).

[20] See generally Section II infra . See in particular the Cremer Report where, at p.70, it is argued that “. . . we believe that competition law can and should, for the foreseeable future, continue to accompany and guide the evolution of the platform economy. Its case law method is particularly well suited for the current state of evolution of the platform economy: a still experimental stage, where the efficiencies of different forms of organisation are not yet well understood and our knowledge and understanding still needs to evolve step by step”, and at p.17, where it is argued that “. . . discussions are only just beginning about novel theories of harm regarding some types of conduct of conglomerate firms that are dominant in a core market characterized by strong network effects and a large user base but, based on these particular strengths, including data, reach out to broader markets. The relevant strategies, and their effects on competition and innovation, will need to be studied more in depth. Similarly, further research on the competitive impact of (big) data pooling might be needed”; the Furman Report considers, at p.117, that “the concerns relating to consumers’ data, and regarding whether any exclusive or preferential practices have an adverse effect on competition within the ad tech sector, are also both highly relevant to the Panel’s aims and CMA findings could significantly advance authorities’ understanding of these issues” and that “the CMA studying the digital advertising market will also boost its knowledge and understanding of digital markets, enhancing its capability to use its tools in these industries”; Monopolkommission, Competition policy: The challenge of digital markets, Special Rep. No 68, 10 (2015), https://www.monopolkommission

.de/images/PDF/SG/s68_fulltext_eng.pdf.

[21] For instance, in the Google Shopping decision, the Commission acknowledges, at 267, that “in fast-growing sectors characterized by short innovation cycles, larger market shares may sometimes turn out to be ephemeral and not necessarily indicative of a dominant position.” Google Shopping Decision, infra note 33.

[22] Case No COMP/M.7217, Facebook/ WhatsApp, (2014), (Facebook/WhatsApp), https://ec.europa.eu/

competition/mergers/cases/decisions/m7217_20141003_20310_3962132_EN.pdf

[23] The criticism of the decision is centered on the alleged inability to detect and prevent so-called “killer” acquisitions, i.e. the idea that the primary intent of the merger is to stop a product’s development without an efficiency rationale. The term is generally employed loosely to refer to both “potential” and “nascent” competition. As Yun explains, these concepts are different, potential competition has a long history in antitrust and competition law and refers to a firm that is predicted to have a competing product at some point. See John M. Yun, Potential Competition and Nascent Competitors, 4 Criterion J. on Innovation 625 (2019). The problem with the proposition that a merger should be blocked to allow for the development of another independent player is assessing the counterfactual. The Commission would have to predict whether the company would have been successful and what its development would have been absent the merger. Additional issues arise from the fact that many startups are invested on the possibility of being bought out in the future, therefore these acquisitions also incentivize innovation. For more on killer acquisitions and potential competition, see John M. Yun, Potential Competition, Nascent Competitors, and Killer Acquisitions, in The GAI Report on the Digital Economy (2020).