Introduction

Almost every site and service you use on the Internet involves content created by someone other than the operator. Most obviously, social media networks such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube rely on their users to create content. But so do Wikipedia and reviews sites such as Yelp and TripAdvisor. The vast majority of news and commentary websites allow users to post comments on each article. Email, messaging services, and video chat all empower users to communicate with each other. And it’s not just content created by users. Google and other search engines catalog websites created by others and attempt to offer users the most relevant results for their search. Each of those websites relies on a complex system of “intermediaries” to host their content, register their domain name, protect those sites against attack, serve the ads that sustain those sites, and much more. Google, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon and others offer third-party apps for download on mobile devices, personal computers, televisions, gaming consoles, watches, and much else.

How did such a complex ecosystem evolve? Try, for a moment, to look at the Internet the way Charles Darwin looked at the complexity of the organic world in the last paragraph of On The Origin of Species. In describing how the simple laws of evolution could produce the wondrous diversity of life we see all around us, Darwin wrote[1]:

It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us. These laws, taken in the largest sense, being Growth with Reproduction; inheritance which is almost implied by reproduction; Variability from the indirect and direct action of the external conditions of life, and from use and disuse; a Ratio of Increase so high as to lead to a Struggle for Life, and as a consequence to Natural Selection, entailing Divergence of Character and the Extinction of less-improved forms. Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.[2]

Now throw in lawyers and America’s uniquely litigious culture: how far would evolution have progressed if every step had been subject to litigation? In the digital world, this is not a facetious question. Many “natural” “laws” have shaped the evolution of today’s Internet. Moore’s Law: processor speeds, or overall processing power for computers, will double every two years.[3] Metcalfe’s law: “the effect of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users of the system.”[4] But one statutory law has made it all possible: Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996.

The law’s premise is simple: “Content creators—including online services themselves—bear primary responsibility for their own content and actions. Section 230 has never interfered with holding content creators liable. Instead, Section 230 restricts only who can be liable for the harmful content created by others.”[5] Specifically, Section 230(c)(1) protects “interactive computer service” (ICS) providers and users from civil actions or state (but not federal) criminal prosecution based on decisions they make as “publishers” with respect to third-party content they are in no way responsible for developing. In its 1997 Zeran decision, the Fourth Circuit became the first appellate court to interpret this provision, concluding that “lawsuits seeking to hold a service provider liable for its exercise of a publisher’s traditional editorial functions—such as deciding whether to publish, withdraw, postpone or alter content—are barred.”[6] A second immunity, Section 230(c)(2)(A) protects (in different ways) decisions to “restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be . . . objectionable,” even if the provider is partly responsible for developing it.[7]

These two immunities, especially (c)(1), allow these ICS providers and users to short-circuit the expensive and time-consuming litigation process quickly, usually with a motion to dismiss—and before incurring the expense of discovery. In this sense, Section 230 functions much like anti-SLAPP laws, which, in 30 states,[8] allow defendants to quickly dismiss strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs)—brought by everyone from businesses fearful of negative reviews to politicians furious about criticism—that seek to use the legal system to silence speech.[9]

Without Section 230 protections, ICS providers would face what the Ninth Circuit, in its landmark Roommates decision, famously called “death by ten thousand duck-bites:”[10] liability at the scale of the billions of pieces of content generated by users of social media sites and other third parties every day. As that court explained, “section 230 must be interpreted to protect websites not merely from ultimate liability, but from having to fight costly and protracted legal battles.”[11] For offering that protection, Section 230(c)(1) has been called the “the twenty-six words that created the Internet.”[12]

What competition and consumer-protection claims does Section 230 actually bar with respect to content-moderation decisions? That depends on whether, when making such decisions, ICS providers and users are exercising the editorial discretion protected by the First Amendment for traditional media operators and new media operators alike under Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo, 418 U.S. 241 (1974). Section 230’s protection is effectively co-extensive with the First Amendment’s. Like anti-SLAPP legislation, Section 230 merely supplies defendants a procedural shortcut to bypass the litigation process and quickly reach the end result that the First Amendment already assures them. That result is that they can moderate content as they see fit—except, just as newspapers may not engage in economic conduct that harms competition, nor are ICS providers acting “as publishers” or “in good faith” when they make content moderation decisions for anti-competitive reasons, and with anti-competitive effect, rather than editorial judgment. The First Amendment protects the right of newspapers to reject ads for editorial reasons, yet a “publisher may not accept or deny advertisements in an ‘attempt to monopolize . . . any part of the trade or commerce among the several States . . . .’”[13] In consumer protection law, deception and other causes of action based on misleading advertising always require that marketing claims be capable of being disproven objectively.

Until recently, most of the debate over rethinking Section 230 has been about increasing liability for content that ICS providers and users do decide to publish. Most notably, in 2017, Congress amended Section 230 for the first time: websites have never been immune from federal criminal prosecution for sex trafficking or anything else, but the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA) allows for state criminal prosecutions and civil liability while strengthening federal law on the promotion of prostitution.[14]

Congress is again debating legislation aimed at combatting child sexual exploitation (CSE) as well as child sexual abuse material (CSAM): the EARN IT Act would create vast, vague liability for enabling not only the transmission of CSAM videos and images but also communications between minors and adults that might amount to solicitation or “grooming.” EARN IT could cause online communications services to compromise encryption or other security features, lead to mandatory age and identity verification, and prompt unconstitutional suppression of anonymous speech.[15]

A flurry of other pending bills would amend Section 230 to hold websites liable for a variety of other content, from misinformation to opioids.[16] Democrats and civil rights groups have particularly focused on claims that Section 230 has obstructed enforcement of anti-discrimination law—even though the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has sued Facebook anyway for allowing buyers of housing ads to target audiences on the basis of race, religion, or gender.[17] Section 230 won’t bar that suit if a court decides that Facebook was responsible, even “in part,” for “the creation or development of [those ads],”[18] just as Roommates.com was held responsible for housing discrimination because it allowed its users to specify race-based preferences in posting, and searching, housing ads on the site.[19] “Internet platforms are generally protected from liability for third-party content,” explains former Rep. Chris Cox (R-CA), Section 230’s primary author, “unless they are complicit in the development of illegal content, in which case the statute offers them no protection.”[20]

In 2020, the political focus of the debate around Section 230 shifted dramatically—from holding ICS providers liable for not doing enough to moderate potentially unlawful or objectionable content to holding them responsible for doing too much content moderation, or at least, moderating content in ways that some find “biased.” Republicans blame Section 230 for preventing them from enforcing antitrust and consumer protection laws against “Big Tech” for discriminating against conservatives in how they treat third-party content. In May, President Trump signed an Executive Order that ordered an all-out attack on Section 230 on multiple fronts.[21] At the President’s direction, the Department of Justice proposed to add an exemption to Section 230 for antitrust claims.[22] Likewise both DOJ and the National Telecommunications Information Administration (NTIA) want to make it easier to sue tech companies for how they moderate third-party content, label it, and decide how to present it to their users. Both DOJ and NTIA claim that courts have misinterpreted Section 230, but while DOJ wants Congress to amend the law, NTIA has filed a petition (as directed by the Executive Order) asking the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to reinterpret the law by rulemaking.[23] Because the NTIA Petition (and the comments filed in response to it, including reply comments by NTIA) provides the most detailed explanation of the new Republican party line on Section 230, it provides a concrete basis for much of the discussion below. TechFreedom’s comments and reply comments in that docket provide a more detailed response than possible here.[24] As requested by the Executive Order, multiple Republican lawmakers have introduced legislation to do the same thing, allowing lawsuits for alleged bias in content moderation.[25]

Democrats have yet to sign onto legislation that would directly regulate bias. Bipartisan draft legislation in the Senate, the PACT Act, would require ICS providers other than “small business providers”[26] to (i) “reasonably inform users about the types of content that are allowed on the interactive computer service,” (ii) follow certain procedures (providing notice to affected users and allowing appeals) after taking down content they created, and (iii) issue annual transparency reports. The FTC could sue ICS providers for failing to take down “policy-violating content” within 14 days of being provided notice of it. But unlike Republican proposals, the PACT Act would not allow ICS providers to be sued for how they interpret or apply their terms of service, nor would it require any kind of neutrality or limit the criteria on which content can be moderated.[27] Thus, this draft bill avoids the most direct interference with the editorial discretion of ICS providers in choosing which content they want to carry. The bill would make two other major amendments to Section 230: it would let state Attorneys General enforce federal civil law and require platforms to take down user content that a court has deemed illegal.[28] While still problematic, compared to other bills to amend Section 230, the PACT Act shows a better understanding of what the law currently is and how content moderation is done[29] Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-IL) has floated a discussion draft of the Online Consumer Protection Act, which would, notwithstanding any protection of Section 230, require all “social media companies” (regardless of size) to “describe the content and behavior the social media platform or online marketplace permits or does not permit on its service” in both human-readable and machine-readable form. The FTC would punish any violations of terms of service as deceptive practices.[30]

This chapter focuses on these and other complaints about “content moderation” because ICS providers are far more likely to be subject to unfair competition and consumer protection claims (meritorious or otherwise) for choosing not to carry, or promote, some third party’s content. The term is used throughout to include not only blocking or removing third party content or those who post it, but also limiting the visibility of that content (e.g., in “Safe Mode”), making it ineligible for amplification through advertising (even if the content remains up), or making it ineligible for “monetization” (i.e., having advertising appear next to it).

We begin by providing an introduction to this statute, its origins, and its application by the courts since 1996. We then explain the interaction between Section 230 and the antitrust and consumer-protection laws. We conclude by discussing current proposals to amend or reinterpret Section 230 aimed specifically at making it easier to bring antitrust and consumer protection suits for content moderation decisions.

I. Congress Enacted Section 230 to Encourage Content Moderation

Recently, DOJ has claimed “the core objective of Section 230 [is] to reduce online content harmful to children.”[31] This is an accurate summary of what the Communications Decency Act, as introduced in the Senate by Sen. John Exon (D-NE), aimed to accomplish. But it is a complete misrepresentation of Section 230, an entirely separate piece of legislation first introduced in the House by Rep. Chris Cox (R-CA) and Ron Wyden (D-OR) as the Internet Freedom and Family Empowerment Act. As Cox recently explained:

One irony . . . persists. When legislative staff prepared the House-Senate conference report on the final Telecommunications Act, they grouped both Exon’s Communications Decency Act and the Internet Freedom and Family Empowerment Act into the same legislative title. So the Cox-Wyden amendment became Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act—the very piece of legislation it was designed to rebuke. Today, with the original Exon legislation having been declared unconstitutional, it is that law’s polar opposite which bears Senator Exon’s label.[32]

Rejecting the idea that Section 230 was “a necessary counterpart” to the rest of the Communications Decency Act as Trump’s DOJ has claimed,[33] Cox notes:

The facts that the Cox-Wyden bill was designed as an alternative to the Exon approach; that the Communications Decency Act was uniformly criticized during the House debate by members from both parties, while not a single Representative spoke in support of it; that the vote in favor of the Cox-Wyden amendment was 420-4; and that the House version of the Telecommunications Act included the Cox-Wyden amendment while pointedly excluding the Exon amendment—all speak loudly to this point.[34]

Newt Gingrich, then Speaker of the House, as Cox notes:

slammed the Exon approach as misguided and dangerous. “It is clearly a violation of free speech, and it’s a violation of the right of adults to communicate with each other,”[said Gingrich], adding that Exon’s proposal would dumb down the internet to what censors believed was acceptable for children to read. “I don’t think it is a serious way to discuss a serious issue,” he explained, “which is, how do you maintain the right of free speech for adults while also protecting children in a medium which is available to both?”[35]

Section 230 provided a simple answer to that question: empowering the providers and users of Internet services to decide for themselves how to approach content moderation. Instead of one right answer for the entire country, there would be a diversity of approaches from which users could choose—a “Utopia of Utopias,” to borrow the philosopher Robert Nozick’s famous phrase.[36] As Rep. Cox put it, “protecting speech and privacy on the internet from government regulation, and incentivizing blocking and filtering technologies that individuals could use to become their own censors in their own households”[37] were among the core purposes of Section 230.

What’s also important to note is that only Section 230, a separate bill that was merged with CDA, is still standing. The Communications Decency Act, which did aim to protect children online, was found to be unconstitutional in a landmark 7-2 decision by the Supreme Court.[38] Justice John Paul Stevens wrote that the CDA placed “an unacceptably heavy burden on protected speech” that “threaten[ed] to torch a large segment of the Internet community.”[39]

Section 230 empowered not only content controls within each household but, perhaps even more importantly, choice among communities with different approaches: Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Gab, and Parler all offer markedly different “utopias” among which users—and advertisers—are free to choose.

It is commonly said that that “Section 230(c)(1) . . . was intended to preserve the rule in Cubby v. Compuserve: platforms that simply post users’ content, without moderating or editing such content, have no liability for the content.”[40] In fact, Section 230 voided both Cubby, Inc. v. CompuServe Inc.[41] and Stratton Oakmont, Inc. v. Prodigy Servs. Co.[42] Both decisions created a version of the “Moderator’s Dilemma,” in which websites have a perverse incentive to avoid content moderation because it will increase their liability. Prodigy, more famously, held websites liable by virtue of attempting to moderate content. Compuserve found no liability, but made clear that this finding depended on the fact that CompuServe had not been provided adequate notice of the defamatory content, implying that such notice would trigger a takedown obligation under a theory of distributor liability.[43] Thus, Compuserve created a perverse incentive not to become aware of the unlawful nature of user content. Similarly, many critics of Section 230 insist the statute is being misapplied because the companies it protects are “obviously publishers”[44]—when the entire purpose of 230(c)(1), as we will see next, is to say that the traditional distinctions among publishers, distributors, and other actors are irrelevant.

II. A Primer on the Statute

To avoid misinterpreting Section 230, practitioners must parse the text of the statute carefully. “The CDA . . . does more than just overrule Stratton Oakmont,” as the Tenth Circuit observed. “To understand the full reach of the statute, we will need to examine some of the technical terms used in the CDA.”[45] Let us do exactly that.

A. Section 230 Protects Far More than Just “Big Tech”

As Section 230 has become more politicized, elected officials and advocates on both sides of the aisle have decried the law as a subsidy to “Big Tech.” This claim is false in at least three ways. First, all three of Section 230’s immunity provisions are worded the same way, protecting any “provider or user of an interactive computer service.”[46] For example, President Trump has used Section 230(c)(1) to dismiss a lawsuit against him for retweeting another user’s content.[47] Every user of social media is likewise protected by 230(c)(1) when they reshare third party content. Second, Section 230 applies to far more than just “social media sites.” The term “information content provider” encompasses a wide variety of services, and thus allows the statute to be truly technologically neutral. Third, as we and other experts noted in a declaration of “principles for lawmakers” concerning the law last year:

Section 230 applies to services that users never interact with directly. The further removed an Internet service—such as a DDOS protection provider or domain name registrar—is from an offending user’s content or actions, the more blunt its tools to combat objectionable content become. Unlike social media companies or other user-facing services, infrastructure providers cannot take measures like removing individual posts or comments. Instead, they can only shutter entire sites or services, thus risking significant collateral damage to inoffensive or harmless content. Requirements drafted with user-facing services in mind will likely not work for these non-user-facing services.[48]

B. What Claims Aren’t Covered by Section 230

Section 230(e) preserves claims raised under federal criminal law, “any law pertaining to intellectual property,”[49] the Electronic Communications Privacy Act and “any similar state law,”[50] certain sex trafficking laws,[51] and “any State law that is consistent with this section.”[52]

Thus, Section 230’s immunities covers civil claims, both state and federal, and all state criminal liability—insofar as they either seek to hold a defendant liable as a publisher ((c)(1)), for content removal decisions ((c)(2)(A)), or for providing tools for content removal decisions to others ((c)(2)(B)), as discussed in the following sections.

The National Association of Attorneys General (NAAG) has asked Congress to amend Section 230 to preserve state criminal liability.[53] But broad preemption of state criminal law reflected a deliberate policy judgment, as Rep. Cox has noted:

the essential purpose of Section 230 is to establish a uniform federal policy, applicable across the internet, that avoids results such as the state court decision in Prodigy. The internet is the quintessential vehicle of interstate, and indeed international, commerce. Its packet-switched architecture makes it uniquely susceptible to multiple sources of conflicting state and local regulation, since even a message from one cubicle to its neighbor inside the same office can be broken up into pieces and routed via servers in different states. Were every state free to adopt its own policy concerning when an internet platform will be liable for the criminal or tortious conduct of another, not only would compliance become oppressive, but the federal policy itself could quickly be undone. All a state would have to do to defeat the federal policy would be to place platform liability laws in its criminal code. Section 230 would then become a nullity. Congress thus intended Section 230 to establish a uniform federal policy, but one that is entirely consistent with robust enforcement of state criminal and civil law.[54]

C. The (c)(1) Immunity Protects the Kind of Editorial

Decisions Made by Publishers, Including Content Moderation

The vast majority of Section 230 cases are resolved under 230(c)(1), a provision that is more complicated than it may seem at first blush: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”[55]

First, (c)(1) protects ICS providers and users—but only insofar as they are not themselves information content providers (ICPs)—i.e., not responsible, even “in part, for the creation or development of information provided through the Internet or any other interactive computer service.”[56] Rep. Cox (R-CA), has called “in part” the two most important words in the statute.[57] “The statute’s fundamental principle,” he explains, “is that content creators should be liable for any illegal content they create.”[58]

Thus, online publications and social networks alike are protected against liability for user comments unless they modify those comments in a way that “contributes to the alleged illegality—such as by removing the word ‘not’ from a user’s message reading ‘[Name] did not steal the artwork’ in order to transform an innocent message into a libelous one.”[59] But these sites are not protected for articles created by their employees or agents.[60] By the same token, Section 230(c)(1) does not apply to warning labels added by Twitter to tweets posted by President Trump or any other user—but nor does adding that label to the tweet make Twitter responsible for the contents of the tweet: Trump remains the ICP of that tweet and Twitter remains the ICP only of the label.

In multiple cases, courts have allowed lawsuits to proceed because they found that websites were at least partially responsible for content creation. The Federal Trade Commission has won two important victories. In 2009, the Tenth Circuit ruled that Section 230 did not protect Accusearch from being sued for illegally selling private telephone records because “a service provider is ‘responsible’ for the development of offensive content only if it in some way specifically encourages development of what is offensive about the content.”[61] The court concluded:

Accusearch was responsible for the . . . conversion of the legally protected records from confidential material to publicly exposed information. Accusearch solicited requests for such confidential information and then paid researchers to obtain it. It knowingly sought to transform virtually unknown information into a publicly available commodity. And as the district court found and the record shows, Accusearch knew that its researchers were obtaining the information through fraud or other illegality.[62]

Similarly, in FTC v. Leadclick Media, LLC, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals allowed the FTC to proceed with its deceptive advertising claims against Leadclick. “While LeadClick did not itself create fake news sites to advertise products,”[63] the court concluded that the company had:

[R]ecruited affiliates for the LeanSpa account that used false news sites. LeadClick paid those affiliates to advertise LeanSpa products online, knowing that false news sites were common in the industry. LeadClick employees occasionally advised affiliates to edit content on affiliate pages to avoid being “crazy [misleading],” and to make a report of alleged weight loss appear more “realistic” by reducing the number of pounds claimed to have been lost. LeadClick also purchased advertising banner space from legitimate news sites with the intent to resell it to affiliates for use on their fake news sites, thereby increasing the likelihood that a consumer would be deceived by that content.[64]

Second, the (c)(1) immunity “precludes courts from entertaining claims that would place a computer service provider in a publisher’s role.”[65] In its 1997 Zeran decision, the Fourth Circuit became the first appellate court to interpret this provision, concluding that “lawsuits seeking to hold a service provider liable for its exercise of a publisher’s traditional editorial functions—such as deciding whether to publish, withdraw, postpone or alter content—are barred.”[66] Thus, courts have held that (c)(1) bars claims that an internet company unlawfully hosted a third party’s defamatory blog post;[67] claims that a social-media platform unlawfully provided an outlet for, or algorithmically “promoted” the content of, terrorists;[68] and claims that an Internet service provider’s failure to remove comments from a chat room amounted to breach of contract and a violation of the civil-rights laws.[69]

D. Section 230(c)(2)(A) Protects Only Content

Moderation Decisions, and Works Differently from (c)(1)

The vast majority of Section 230 cases are resolved under 230(c)(1).[70] Following Zeran, courts have resolved many content moderation cases under both (c)(1) and (c)(2)(A), or simply (c)(1) because the analysis is easier.[71] The two provide somewhat overlapping, but different protections for content moderation. Subparagraph 230(c)(2)(A) says that:

No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be held liable on account of any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected . . . .[72]

Note how much this provision differs from (c)(1). On the one hand, (c)(2)(A)’s protections are broader: they do not depend on the ICS/ICP distinction, so (c)(2)(A) applies even when an ICS provider or user is responsible, at least in part, for developing the content at issue. On the other, its immunity is narrower, protecting only against liability only for content moderation, not liability for content actually published.[73] Furthermore, that protection is contingent on a showing of good faith. As we shall see, much of the current policy debate over rewriting or reinterpreting Section 230 rests on the notion that only (c)(2)(A) should protect content moderation,[74] and that the kinds of content moderation decisions it protects should be narrowed significantly.[75]

E. Section 230(c)(2)(B) Protects the Provision of Content Removal Tools to Others

While it is often said that Section 230 contains two immunities—(c)(1) and (c)(2)—it actually contains three, as (c)(2)(A) and (c)(2)(B) work differently and serve different functions. While (c)(2)(A) protects ICS users and providers in making content removal decisions, (c)(2)(B) protects “any action taken to enable or make available to information content providers or others the technical means to restrict access to material described in [(c)(2)(B)].”[76] There has been relatively little litigation involving this provision, most of which involves anti-malware tools.[77] But (c)(2)(B) also protects makers of the parental control tools built into operating systems for computers, mobile devices, televisions, gaming consoles, etc., as well as additional tools and apps that users can add to those devices. Likewise, (c)(2)(B) protects other tools offered to users, such as Social Fixer, a popular online application that allows consumers to tailor the content they receive on Facebook.[78] With a few clicks, consumers can hide posts involving specified keywords or authors, filter out political content, or block targeted advertisements. Like parental tools, Social Fixer puts the consumer in control; in the language of Section 230(c)(2)(B), it provides the “technical means” by which the consumer chooses what fills her computer screen.

F. Does Section 230 Require “Neutrality?”

In Marshall’s Locksmith v. Google, the D.C. Circuit dismissed, under Section 230, false advertising and Sherman Act claims by locksmiths who claimed that “Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo! have conspired to ‘flood the market’ of online search results with information about so-called ‘scam’ locksmiths, in order to extract additional advertising revenue.”[79] The case makes clear that Section 230 does bar some antitrust claims, but also merits discussion because of the potentially confusing nature of its discussion of “neutrality.”

Plaintiffs alleged that the way search engines displayed “scam” locksmith listings on their map tools alongside those for “legitimate” locksmiths “allows scam locksmiths to amplify their influence.”[80] They argued that Section 230(c)(1) ought not apply because the maps constituted “[e]nhanced content that was derived from third-party content, but has been so augmented and altered as to have become new content and not mere editorialization . . . .”[81]

The court disagreed. “We have previously held,” it noted, “that ‘a website does not create or develop content when it merely provides a neutral means by which third parties can post information of their own independent choosing online.’”[82] The defendants in the case at hand, it continued, had “use[d] a neutral algorithm” to “convert third-party indicia of location into pictorial form.”[83] The defendants’ algorithms were “neutral” in that they did “not distinguish between legitimate and scam locksmiths . . . .” The (c)(1) immunity thus defeated the locksmiths’ claims.[84]

“Because the defendants’ map pinpoints hew to the third-party information from which they are derived,” the court did not need to “decide precisely when an entity that derives information can be considered to have ‘creat[ed] or develop[ed]’ it.”[85] This and other lines in the opinion might give the impression that “neutrality” is a prerequisite to all forms of Section 230 immunity. But “neutrality” is usually not such a condition. To hold otherwise would nullify the many opinions holding that a defendant enjoys Section 230 immunity whenever it acts as a publisher. No publisher that exercises editorial discretion can be wholly “neutral.” As Prof. Eric Goldman notes, “The ‘neutrality’ required in this case relates only to the balance between legal and illegal content.”[86]

III. Section 230 Bars Antitrust Claims Only Insofar as the First Amendment Would Bar Them Too

Does Section 230 bar otherwise valid antitrust claims? No. Properly understood, both the (c)(1) and (c)(2)(A) immunities protect decisions to moderate or prioritize third-party content exactly inasmuch as the First Amendment itself would apply. Just as the First Amendment does not offer complete immunity to newspapers for how they handle third-party content, neither does Section 230.

A. Both (c)(1) and (c)(2)(A) Protect the Exercise of a Publisher’s

Editorial Discretion Inasmuch as It Would Be Protected by the First Amendment

The (c)(1) immunity bars only those claims that hold an ICS provider (or user) liable as the “publisher” of content provided by another—i.e., “deciding whether to publish, withdraw, postpone or alter content.”[87] In other words, (c)(1) protects the exercise of editorial discretion protected by the First Amendment itself: “The choice of material to go into a newspaper, and the decisions made as to limitations on the size and content of the paper, and treatment of public issues and public officials—whether fair or unfair—constitute the exercise of editorial control and judgment.”[88] “Since all speech inherently involves choices of what to say and what to leave unsaid . . . for corporations as for individuals, the choice to speak includes within it the choice of what not to say.”[89] In Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Group of Boston, the Supreme Court barred the city of Boston from forcing organizers’ of the St. Patrick’s Day parade to include pro-LGBTQ individuals, messages, or signs that conflicted with the organizer’s beliefs.[90] The “general rule,” declared the court, is “that the speaker has the right to tailor the speech, applies not only to expressions of value, opinion, or endorsement, but equally to statements of fact the speaker would rather avoid.”[91] Courts have recognized that social media publishers have the same rights under Miami Herald as newspapers to reject content (including ads) provided to them by third parties.[92]

The (c)(2)(A) immunity does not explicitly turn on whether the cause of action involves the ICS provider being “treated as the publisher,” yet it clearly protects a subset of the cluster of rights protected by Miami Herald: decisions to “restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected.”[93] Including the broad catch-all “otherwise objectionable” ensures that this immunity is fully coextensive with the First Amendment right of ICS providers and users, recognized under Hurley, to “avoid” speech they find repugnant.

As the Tenth Circuit has noted, “the First Amendment does not allow antitrust claims to be predicated solely on protected speech.”[94] Thus, Moody’s publication of an article giving a school district’s bonds a negative rating could not give rise to an antitrust claim.[95] In all of the cases cited by the plaintiff, “the defendant held liable on an antitrust claim engaged in speech related to its anticompetitive scheme,” but in each, that speech was incidental to the antitrust violation.[96] Notably, in none of these cases was the “speech” at issue the exercise of editorial discretion not to publish, or otherwise associate with, the speech of others. Antitrust suits against web platforms must be grounded in economic harms to competition, not the exercise of editorial discretion.[97] Prof. Eugene Volokh (among the nation’s top free speech scholars) explains:

it is constitutionally permissible to stop a newspaper from “forcing advertisers to boycott a competing” media outlet, when the newspaper refuses advertisements from advertisers who deal with the competitor. Lorain Journal Co. v. United States, 342 U.S. 143, 152, 155 (1951). But the newspaper in Lorain Journal Co. was not excluding advertisements because of their content, in the exercise of some editorial judgment that its own editorial content was better than the proposed advertisements. Rather, it was excluding advertisements solely because the advertisers—whatever the content of their ads—were also advertising on a competing radio station. The Lorain Journal Co. rule thus does not authorize restrictions on a speaker’s editorial judgment about what content is more valuable to its readers.[98]

This is true even against “virtual monopolies.” As Volokh explains, the degree of a media company’s market power does not diminish the degree to which the First Amendment protects its editorial discretion.[99]

For example, a federal court dismissed an antitrust lawsuit alleging that Facebook had attempted to eliminate an advertising competitor by blocking users of a browser extension that super-imposed its own ads onto Facebook’s website:

Facebook has a right to control its own product, and to establish the terms with which its users, application developers, and advertisers must comply in order to utilize this product. . . . Facebook has a right to protect the infrastructure it has developed, and the manner in which its website will be viewed.[100]

The court added:

There is no fundamental right to use Facebook; users may only obtain a Facebook account upon agreement that they will comply with Facebook’s terms, which is unquestionably permissible under the antitrust laws. It follows, therefore, that Facebook is within its rights to require that its users disable certain products before using its website.[101]

Antitrust law is so well-settled here that the court did not even need to mention the First Amendment. Instead, the court simply cited Trinko: “as a general matter, the Sherman Act ‘does not restrict the long recognized right of [a] trader or manufacturer engaged in an entirely private business, freely to exercise his own independent discretion as to parties with whom he will deal.’”[102] That “discretion” closely parallels the First Amendment right of publishers to exclude content they find objectionable under Miami Herald.[103]

Just as The Lorain Journal was not acting “as a publisher” when it refused to host ads from advertisers that did not boycott its radio competitor, it was also not acting “in good faith.” In this sense, the two concepts serve essentially the same function as limiting features. Each ensures that the immunity to which it applies does not protect conduct that would not be protected by the First Amendment. Thus, either immunity could be defeated by showing that the actions at issue were not matters of editorial discretion, but of anti-competitive conduct.

B. How Courts Might Decide Whether Section 230 Bars Specific Competition Law Claims

Epic Games recently began offering users of Fortnite, its wildly popular gaming app, the ability to make in-game purchases directly from Fortnite’s website, thus avoiding the 30% fee charged for all purchases made through Apple’s App Store. Because this violated Apple’s longstanding terms of service for the App Store, Apple banned the game. Fortnite responded by filing an antitrust suit.[104] Apple has not raised Section 230 as a defense, and for good reason: Apple may or may not have violated the antitrust laws, but it was clearly not operating as a “publisher” when it enforced rules intended to protect a key part of its business model.

By contrast, if Facebook refused to carry ads from publishers that also bought ads on one of Google’s ad networks, the situation would be exactly the same as in Lorain Journal. Facebook’s potential liability would not be because the site was being “treated as the publisher” of ads it refused to run. The same rule should hold in other cases, even though they may be more complicated.

While Google’s AdSense network may appear to be very different from Facebook—Facebook is clearly the “publisher” of its own site while AdSense merely fills ad space on webpages published by others—AdSense is no less an ICP than is Facebook. Thus, Google can claim Section 230 immunity for decisions it makes to limit participation in AdSense (i.e., on which sites AdSense ads appear). Still, Google would be no more protected by Section 230 than The Lorrain Journal was by the First Amendment if Google refused to provide display ads via its AdSense network on third party websites simply because those sites also showed display ads from other ad networks.

A somewhat more complicated case is presented by the European Commission’s 2016 complaint against Google for how the company handled exclusivity in a different product: AdSense for Search, which displays ads alongside search results in the custom search engines Google makes available for third party websites to embed on their sites (generally to search the site’s contents).[105] (The Commission fined Google €1.5 billion in 2019.[106]) The exclusivity clauses Google imposed from 2006 to 2009 seem little different from Lorrain Journal or the AdSense hypothetical discussed above. But starting in 2009, Google began replacing exclusivity clauses with “Premium Placement” clauses that worked differently.[107] These clauses required “third parties to take a minimum number of search ads from Google and reserve the most prominent space on their search results pages to Google search ads.” [108] Again, it is hard to see how Google could convince an American court that excluding participation in AdSense for Search based on these restrictions would be an exercise in a publisher’s editorial judgment—and a plaintiff would have a good argument that these requirements were not imposed “in good faith.” (Whether or not such arguments would prevail under U.S. antitrust law would, of course, be an entirely separate question.) But Google’s requirement that “competing search ads cannot be placed above or next to Google search ads”[109] is at least a harder question. Google would have a much stronger argument that this requirement prevented users from mistaking ads provided by third parties from its own ads. Google might object to those third-party ads being shown right next to its own search results not only because their (potentially) lower quality could diminish user expectations of the value of Google’s search ads across the board, including on Google.com, but also because Google has no editorial control over those ads, which might include content that violates Google’s terms of service.

This case would be essentially the same as Google’s refusal to allow participation in its AdSense network by webpages that display content that violates Google’s terms of service—that Google ads do not appear next to hate speech, misinformation, etc. Many large publications have found that Google will refuse to run ads on specific pages because content in the user comments section violated its terms of service. When the scale of such content has become large enough, Google has refused to run ads on the site altogether unless the site separates the comments section from the article, and runs ads only on the article. Some sites, like Boing Boing, have done just that, but as we shall see, Google’s enforcement of this policy recently sparked a political uproar.

Essentially the same analysis would apply over blocking apps from the app store: Apple, Google, Amazon and Microsoft all block pornography apps from their stores.[110] All have banned Gab, the “free speech” social network where little but pornography is moderated, from offering an app in their stores.[111] Gab may, in some sense, be a competitor to these companies, but each would have an easy argument that they were acting as “publishers,” and in “good faith,” when they banned the Gab app.

C. Why Political Bias in Content Moderation Cannot Give Rise to Antitrust Violations

Now consider competition claims that are even more clearly about the exercise of editorial discretion—claims regarding blocking specific users or publications. When a plaintiff brings both a general antitrust claim and a specific claim about content removal, Section 230 bars the latter but not the former. In Brittain v. Twitter, for example, Craig Brittain sued Twitter for suspending four of his accounts.[112] The court dismissed all claims under Section 230, save an antitrust claim that did not “arise out of Twitter’s deletion of the Brittain Accounts.”[113] That claim, which attacked Twitter’s alleged “monopolization” of the “social media networking market,”[114] was assessed separately under the antitrust laws. (It failed.)

But at least in one case, a plaintiff clearly alleged that account suspension violated a state unfair competition law. The case offers the most thorough explanation of why Section 230 bars such claims about “unfair” or “biased” exercises of editorial discretion. When Jared Taylor, a leading white supremacist,[115] first joined Twitter in 2011, the site did not bar (indeed, it all but pledged not to censor) extremist content. But the site reserved the right to revise its terms of service, and in 2017 it “announced ‘updated . . . rules’” on hateful and violent content. These included a requirement that users “not affiliate with organizations that . . . use or promote violence against civilians to further their causes.” Acting under these rules, Twitter banned Taylor and his publication.[116] Taylor then sued Twitter for blocking him (and his white-nationalist publication American Renaissance) from the site.

Although it dismissed most of Taylor’s lawsuit under Section 230, the trial court let an unfair-competition claim proceed. The California Court of Appeal reversed,[117] holding that Section 230 barred all of Taylor’s claims. The core question, the court observed, is whether the plaintiff’s claim attacks decisions the defendant made while acting as a publisher.[118] Such publishing decisions, the court continued, include decisions to “restrict or make available certain material.” Thus, a defendant’s decision to allow a user to have, or to bar a user from having, a social-media account falls squarely within the Section 230 immunity. “Any activity,” the court concluded, “that can be boiled down to deciding whether to exclude material that third parties seek to post online is perforce immune under section 230.”[119] The court’s full analysis offers an excellent summary of current case law.[120]

Conceding error on remand, the trial judge wrote: “I now realize that . . . [i]n the evaluation of plaintiffs’ UCL claim, framing the salient question as whether Twitter is being treated as a publisher[,] or [as the party] whose speech is the basis for the claim, is a single indivisible question.”[121] In other words, as we have argued, being treated “as a publisher” means being held liable on the basis of the exercise of free speech rights, including the editorial decision to remove objectionable content.

D. Both the First Amendment and Section 230 Protect the Right of Ad Platforms to Disassociate from Content They Find Objectionable

Section 230(c)(1) protects a website operator’s right to “demonetize” third-party content creators who upload content to the site—i.e., leaving their content up, but declining to run ads next to it. Thus, for example, a court dismissed a suit alleging violations of the Sherman and Lanham acts after YouTube “demonetized the ‘Misandry Today’ channel (which purported to expose anti-male bias).”[122] The court equated removal of content and demonetization: “Both fall under the rubric of publishing activities.”[123]

The same result applies when publishers of any interactive computer service refuse to allow their content to appear on third party pages—whether that content is an ad or other embeddable function. Consider the most controversial case of “demonetization” by an advertising platform: “NBC News attempted,” the co-founders of the rightwing website The Federalist wrote in June 2020, “to use the power of Google to cancel our publication.”[124] After NBC published an exposé about racist comments posted by readers of The Federalist on its articles, Google told the site that it would no longer run ads on the site unless the site moderated content that violated the AdSense Terms of Service. The Federalist never filed a lawsuit—and for good reason: both the First Amendment and Section 230 would have blocked any antitrust (or other) suit.

The Federalist received, not a dose of politically motivated punishment, but a common lesson in the difficulty of content moderation. Websites across the political spectrum have had their content flagged in the same way. Boing Boing (a tech news site) handled the situation by putting user comments for each article (with Google ads) on a separate page (without ads). TechDirt (a leading site about technology that no one would ever accuse of being “right wing”) kept user comments on the same page as each article.[125]

The difficulties of content moderation cannot, constitutionally, be solved by the NTIA Petition or any other government action. Writing about his site’s experience with these issues, TechDirt’s editor Mike Masnick explained:

[T]here are currently no third-party ads on Techdirt. We pulled them down late last week, after it became impossible to keep them on the site, thanks to some content moderation choices by Google. In some ways, this is yet another example of the impossibility of content moderation at scale . . . .

The truth is that Google’s AdSense (its third-party ad platform) content moderation just sucks. In those earlier posts about The Federalist’s situation, we mentioned that tons of websites deal with those “policy violation” notices from Google all the time. Two weeks ago, it went into overdrive for us: we started receiving policy violation notices at least once a day, and frequently multiple times per day. Every time, the message was the same, telling us we had violated their policies (they don’t say which ones) and we had to log in to our “AdSense Policy Center” to find out what the problem was. Every day for the ensuing week and a half (until we pulled the ads down), we would get more of these notices, and every time we’d log in to the Policy Center, we’d get an ever rotating list of “violations.” But there was never much info to explain what the violation was. Sometimes it was “URL not found” (which seems to say more about AdSense’s shit crawler than us). Sometimes it was “dangerous and derogatory content.” Sometimes it was “shocking content.”[126]

Other large publications have experienced similar problems. Consider Slate (generally considered notably left-of-center), whose experience illustrates the limits of algorithmic content moderation as a way of handling the scale problem of online content:

Last Thursday, Google informed Slate’s advertising operations team that 10 articles on the site had been demonetized for containing “dangerous or derogatory content.” The articles in question covered subjects like white supremacy, slavery, and hate groups, and most of them quoted racial slurs. They included pieces on the racist origins of the name kaffir lime, the 2017 police brutality movie Detroit, Joe Biden’s 1972 Senate run, and a Twitter campaign aimed at defaming Black feminists, which all had quotes containing the N-word . . . .

Needless to say, the articles were not promoting the discriminatory ideologies affiliated with these slurs but rather reporting on and analyzing the context in which they were used.

Once flagged by the algorithm, the pages were not eligible to earn revenue through Ad Exchange. Slate appealed the moderation decisions through Google’s ad platform last Thursday morning, as it normally would when a demonetization it feels is unjustified occurs. Not long after, as part of the reporting of this story, I contacted Google’s communications department, whose personnel said they would contact the engineering team to look into it. The pages were subsequently remonetized by Friday morning.[127]

So, yes, the tool Google uses to decide whether it wants to run its ads next to potentially objectionable content is highly imperfect. Yes, everyone can agree that it would be better if this tool could distinguish between discussions of racism and racism itself—and exactly the same thing can be said of the algorithms Facebook and (to a lesser degree) Twitter apply to moderate user content on their sites. But these simply are not problems for the government to solve. The First Amendment requires us to accept that the exercise of editorial discretion will always be messy. This is even more true of digital media than it is of traditional media, as Masnick’s Impossibility Theorem recognizes: “Content moderation at scale is impossible to do well. More specifically, it will always end up frustrating very large segments of the population and will always fail to accurately represent the ‘proper’ level of moderation of anyone.”[128]

Google has a clear First Amendment right not to run its ads next to content it finds objectionable. If websites want to run Google ads next to their comments section, they have a contractual obligation to remove content that violates Google’s terms of service for their advertising platform. Simply relying on users to downrank objectionable content, rather than removing it altogether—as The Federalist apparently did—will not suffice if the objectionable content remains visible on pages where Google Ads appear. It is worth noting that, while TechDirt might reasonably expect its readers to downrank obviously racist content, the exact opposite has happened on The Federalist:

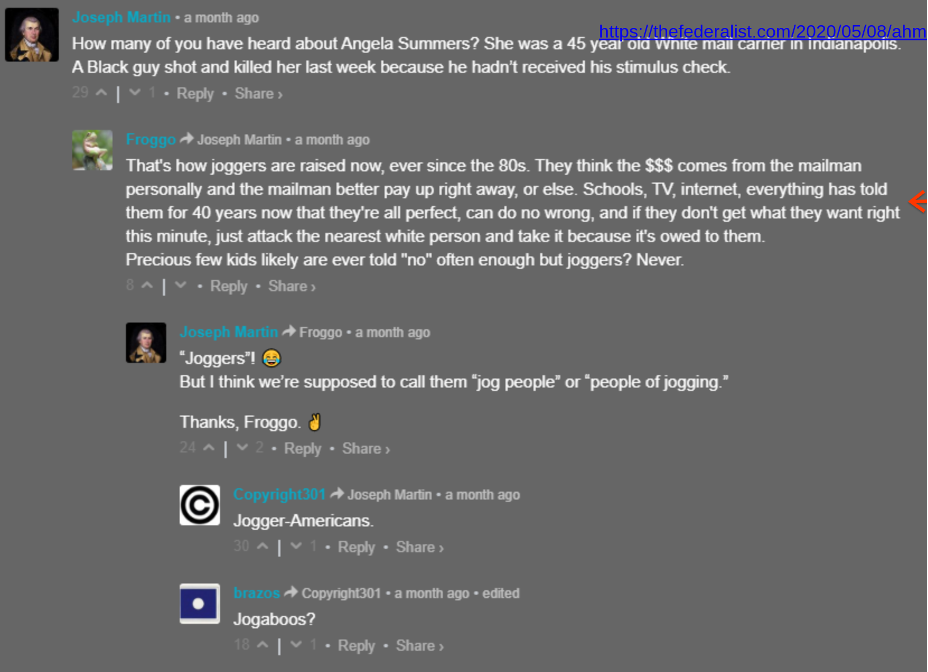

(These comments use the term “jogger” as code for the n-word, in reference to the racially motivated murder of “Ahmaud Arbery, the young black man who was shot dead in February while he was running in a suburban neighborhood in Georgia.”[129])

Given the inherent challenges of content moderation at scale—and given how little attention most comment sections receive—it would be unfair to generalize about either The Federalist or its overall readership based on such examples. Nonetheless, Google has a right—guaranteed by the First Amendment—to insist that its ads not appear next to, or even anywhere on a site that hosts, a single such exchange. In exercising this right, Google also protects the right of advertisers not to be associated with racism and other forms of content they, in their sole discretion, deem objectionable. In making such decisions, Google is exercising its editorial discretion of AdSense, which clearly qualifies as an ICS. An advertising broker, after all, acts as a publisher no less than a newspaper does. Both a newspaper and an ad broker decide where content goes and how it is presented; the one just does this with stories, the other with ads. Thus, Section 230(c)(1) protects Google’s right to exercise editorial discretion in how it places ads just as it protects Google’s right to exercise such discretion over what content appears on YouTube.

IV. Section 230 and Consumer Protection Law

Even more than antitrust, Republicans have also insisted that consumer protection law should be used to police “bias.” Multiple Republican legislative proposals would use existing consumer protection law to enforce promises (allegedly) made by social media companies to remain “neutral” in content moderation and other decisions about configuring the user experience.[130] The Executive Order contemplates the FTC and state attorneys general using consumer protection law to declare unfair or deceptive “practices by entities covered by section 230 that restrict speech in ways that do not align with those entities’ public representations about those practices.”[131] The NTIA Petition to the FCC argues:

if interactive computer services’ contractual representations about their own services cannot be enforced, interactive computer services cannot distinguish themselves. Consumers will not believe, nor should they believe, representations about online services. Thus, no service can credibly claim to offer different services, further strengthening entry barriers and exacerbating competition concerns.[132]

The underlying premise of this argument false. As explained below, consumer protection law cannot enforce such claims because, to be enforceable, claims must be specific, objectively verifiable, and related to commercial transactions, not social policy. These requirements are ultimately rooted in the First Amendment itself. The category of “representations” about content moderation that could, perhaps, be enforced in court would be accordingly narrow.

Perhaps recognizing that the statements of neutrality they point to (often made in Congressional hearings in response to badgering by Republican lawmakers) will not give rise to liability today, NTIA proposes to require social media providers, as a condition of 230(c)(2)(A) protection for their content moderation practices, to “state plainly and with particularity the criteria the interactive computer service employs in its content-moderation practices.”[133] (NTIA also asks the FCC to reinterpret Section 230 so that (c)(1) no longer protects content moderation.) Furthermore, NTIA would require each ICS provider to commit not to “restrict access to or availability of material on deceptive or pretextual grounds” and to “apply its terms of service or use to restrict access to or availability of material that is similarly situated to material that the interactive computer service intentionally declines to restrict.”[134] Similar concepts can be found in multiple Republican bills.[135] Such transparency mandates will also fail under the First Amendment.

Republicans now find themselves in the awkward position of advocating something like the FCC’s old Fairness Doctrine, under which broadcasters were required to ensure that all “positions taken by responsible groups” received airtime. Republicans fiercely opposed the Fairness Doctrine long after President Reagan effectively ended it in 1987—all the way through the 2016 Republican platform.[136]

A. Community Standards Are Non-Commercial Speech,

which Cannot Be Regulated via Consumer Protection Law

The Federal Trade Commission has carefully grounded its deception authority in the distinction long drawn by the Supreme Court between commercial and non-commercial speech in Central Hudson Gas Elec. v. Public Serv. Comm’n, 447 U.S. 557 (1980) and its progeny. Commercial speech is speech which “[does] no more than propose a commercial transaction.”[137] In Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Human Rel. Comm’n, the Supreme Court upheld a local ban on referring to sex in the headings for employment ads. In ruling that the ads at issue were not non-commercial speech (which would have been fully protected by the First Amendment), it noted: “None expresses a position on whether, as a matter of social policy, certain positions ought to be filled by members of one or the other sex, nor does any of them criticize the Ordinance or the Commission’s enforcement practices.”[138] In other words, a central feature of commercial speech is that it is “devoid of expressions of opinions with respect to issues of social policy.”[139] This is the distinction FTC Chairman Joe Simons was referring to when he told lawmakers this summer that the issue of social media censorship is outside the FTC’s remit because “our authority focuses on commercial speech, not political content curation.”[140]

While “terms of service” for websites in general might count as commercial speech, the kind of statement made in “community standards” clearly “expresses a position on . . . matter[s] of social policy.” Consider just a few such statements from Twitter’s “rules”:

Violence: You may not threaten violence against an individual or a group of people. We also prohibit the glorification of violence. Learn more about our violent threat and glorification of violence policies.

Terrorism/violent extremism: You may not threaten or promote terrorism or violent extremism. . . .

Abuse/harassment: You may not engage in the targeted harassment of someone, or incite other people to do so. This includes wishing or hoping that someone experiences physical harm.

Hateful conduct: You may not promote violence against, threaten, or harass other people on the basis of race, ethnicity, national origin, caste, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, religious affiliation, age, disability, or serious disease.[141]

Each of these statements clearly “expresses a position on . . . a matter of social policy,”[142] and therefore is clearly non-commercial speech that merits the full protection of the First Amendment under the exacting standards of strict scrutiny. “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.”[143] Consumer protection law simply does not apply to such claims—because of the First Amendment’s protections for non-commercial speech.

B. The First Amendment Does Not Permit Social Media

Providers to Be Sued for “Violating” their Current Terms of Service, Community Standards, or Other Statements About Content Moderation

Given the strong protection a website’s terms of service enjoy under the First Amendment, it is no surprise that attempts to enforce statements about political neutrality via consumer protection law have failed—and that no American consumer protection agency has actually pursued such claims in an enforcement action.

Understanding why such claims are unenforceable starts in the rhetorical hotbed that is cable news. In 2004, MoveOn.org and Common Cause asked the FTC to proscribe Fox News’ use of the slogan “Fair and Balanced” as a deceptive trade practice.[144] The two groups acknowledged that Fox News had “no obligation whatsoever, under any law, actually to present a ‘fair’ or ‘balanced’ presentation of the news,”[145] but argued: “What Fox News is not free to do, however, is to advertise its news programming—a service it offers to consumers in competition with other networks, both broadcast and cable—in a manner that is blatantly and grossly false and misleading.”[146] FTC Chairman Tim Muris (a Bush appointee) responded pithily: “I am not aware of any instance in which the [FTC] has investigated the slogan of a news organization. There is no way to evaluate this petition without evaluating the content of the news at issue. That is a task the First Amendment leaves to the American people, not a government agency.”[147]

Deception claims always involve comparing marketing claims against conduct.[148] Muris meant that, in this case, the nature of the claims (general claims of fairness) meant that their accuracy could not be assessed without the FTC sitting in judgment of how Fox News exercised its editorial discretion. The “Fair and Balanced” claim was not, otherwise, verifiable—which is to say that it was not objectively verifiable.

Prager “University,” the leading creator of “conservative” video content, attempted to make essentially the same deceptive marketing claim against YouTube in a case dismissed by the Ninth Circuit. Despite having over 2.52 million subscribers and more than a billion views of “5-minute videos on things ranging from history and economics to science and happiness,”[149] PragerU sued YouTube for “unlawfully censoring its educational videos and discriminating against its right to freedom of speech.”[150] Specifically, PragerU alleged that roughly a sixth of the site’s videos had been flagged for YouTube’s Restricted Mode,[151] an opt-in feature that allows parents, schools, and libraries to restrict access to potentially sensitive content (and is turned on by fewer than 1.5% of YouTube users).[152] After dismissing PragerU’s claims that YouTube was a state actor denied First Amendment protection, the Ninth Circuit ruled:

YouTube’s braggadocio about its commitment to free speech constitutes opinions that are not subject to the Lanham Act. Lofty but vague statements like “everyone deserves to have a voice, and that the world is a better place when we listen, share and build community through our stories” or that YouTube believes that “people should be able to speak freely, share opinions, foster open dialogue, and that creative freedom leads to new voices, formats and possibilities” are classic, non-actionable opinions or puffery. Similarly, YouTube’s statements that the platform will “help [one] grow,” “discover what works best,” and “giv[e] [one] tools, insights and best practices” for using YouTube’s products are impervious to being “quantifiable,” and thus are non-actionable “puffery.” The district court correctly dismissed the Lanham Act claim.[153]

Roughly similar to the FTC’s deception authority, the Lanham Act requires proof that (1) a provider of goods or services made a “false or misleading representation of fact,”[154] which (2) is “likely to cause confusion” or deceive the general public about the product.[155] Puffery fails both requirements because it “is not a specific and measurable claim, capable of being proved false or of being reasonably interpreted as a statement of objective fact.”[156] The FTC’s bedrock 1983 Deception Policy Statement declares that the “Commission generally will not pursue cases involving obviously exaggerated or puffing representations, i.e., those that the ordinary consumers do not take seriously.”[157]

There is simply no way social media services can be sued under either the FTC Act (or state baby FTC acts) or the Lanham Act for claims they make today about their content moderation practices. Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey said this in Congressional testimony in 2018: “Twitter does not use political ideology to make any decisions, whether related to ranking content on our service or how we enforce our rules.”[158] This claim is no less “impervious to being ‘quantifiable’” than YouTube’s claims.[159]

Moreover, “[i]n determining the meaning of an advertisement, a piece of promotional material or a sales presentation, the important criterion is the net impression that it is likely to make on the general populace.”[160] Thus, isolated statements about neutrality or political bias (e.g., in Congressional testimony) must be considered in the context of the other statements companies make in their community standards, which broadly reserve discretion to remove content or users. Furthermore, the FTC would have to establish the materiality of claims, i.e., that an “act or practice is likely to affect the consumer’s conduct or decision with regard to a product or service. If so, the practice is material, and consumer injury is likely, because consumers are likely to have chosen differently but for the deception.”[161] In the case of statements made in Congressional testimony or in any other format besides a traditional advertisement, the Commission could not simply presume that the statement was material.[162] Instead, the Commission would have to prove that consumers would have acted differently but for the deception. These requirements—objective verifiability (about facts, rather than opinions) and materiality—are not simply doctrinal formalities of current consumer protection law that could be bypassed by new legislation. Instead, they reflect the outer boundaries of how far the government may go in regulating speech without violating the First Amendment. In short, the First Amendment allows the government to enforce marketing claims, but not to police the exercise of editorial discretion.

C. The First Amendment Will Not Permit the Government to Compel More Specific Claims

Because current claims by social media companies about their editorial practices are “impervious to being ‘quantifiable,’ and thus are non-actionable ‘puffery,’” the NTIA Petition and several Republican bills propose to require more specific statements. But does anyone seriously believe that the First Amendment would—whether through direct mandate or as the condition of tax exemption, subsidy, legal immunity, or some other benefit—permit the government to require book publishers to “state plainly and with particularity the criteria” (as NTIA proposes) by which they decide which books to publish, or newspapers to explain how they screen letters to the editor, or cable TV news shows to explain which guests they book—let alone enforce adherence to those criteria the exercise of editorial discretion?

Startlingly, NTIA professes to see nothing unconstitutional about such a quid pro quo, at least when quo is legal immunity:

To the contrary, the Supreme Court has upheld the constitutionality of offers special liability protections in exchange for mandated speech. In Farmer’s Union v. WDAY, the Court held that when the federal government mandates equal time requirement for political candidates—a requirement still in effect, this requirement negates state law holding station liable for defamation for statements made during the mandated period. In other words, the Court upheld federal compelled speech in exchange for liability protections. Section 230’s liability protections, which are carefully drawn but come nowhere near to compelling speech, are just as constitutionally unproblematic if not more so.[163]

The problem with this argument should be obvious: the 1959 Supreme Court decision cited by NTIA involved only broadcasters, which do not enjoy the full protection of the First Amendment. Thus, this argument is no more applicable to non-broadcast media than is the Supreme Court’s 1969 decision Red Lion upholding the Fairness Doctrine for broadcasters.[164] Yet the NTIA’s “plain and particular criteria” mandate goes far beyond even what the Fairness Doctrine required. Such disclosure mandates offend the First Amendment for at least three reasons. First, community standards and terms of service are themselves non-commercial speech.[165] Deciding how to craft them is a form of editorial discretion protected by the First Amendment, and forcing changes in how they are written is itself a form of compelled speech—no different from forcing a social media company’s other statements about conduct it finds objectionable on, or off, its platform. “Mandating speech that a speaker would not otherwise make necessarily alters the content of the speech.”[166] The Court said that in a ruling striking down a North Carolina statute that required professional fundraisers for charities to disclose to potential donors the gross percentage of revenues retained in prior charitable solicitations. The Court declared that the “the First Amendment guarantees ‘freedom of speech,’ a term necessarily comprising the decision of both what to say and what not to say.”[167] The Court will not allow compelled disclosure for something that is relatively objective and quantifiable, how could it allow compelled disclosure of something far more subjective?

Second, forcing a social media site to attempt to articulate all of the criteria for its content moderation practices while also requiring those criteria to be as specific as possible will necessarily constrain what is permitted in the underlying exercise of editorial discretion. Community standards and terms of service are necessarily overly reductive; they cannot possibly anticipate every scenario. If the Internet has proven anything, it is that there is simply no limit to human creativity in finding ways to be offensive in what we say and do in interacting with other human beings online. It is impossible to codify “plainly and with particularity” all of the reasons why online content and conduct may undermine Twitter’s mission to “serve the public conversation.”[168] Thus, compelling disclosure of decision-making criteria and limiting media providers to them in making content moderation decisions will necessary compel speech on a second level: forcing the website to carry speech it would prefer not to carry.

Third, even if the government argued that the criteria it seeks to compel social media providers to disclose are statements of fact (about how they conduct content moderation) rather than statements of opinion, the Court has explicitly rejected such a distinction. Citing cases in which the court had struck down compelled speech requirements, such as displaying the slogan “Live Free or Die” on a license plate,[169] the Court noted:

These cases cannot be distinguished simply because they involved compelled statements of opinion while here we deal with compelled statements of “fact”: either form of compulsion burdens protected speech. Thus, we would not immunize a law requiring a speaker favoring a particular government project to state at the outset of every address the average cost overruns in similar projects, or a law requiring a speaker favoring an incumbent candidate to state during every solicitation that candidate’s recent travel budget. Although the foregoing factual information might be relevant to the listener, and, in the latter case, could encourage or discourage the listener from making a political donation, a law compelling its disclosure would clearly and substantially burden the protected speech.[170]

The same is true here: the First Amendment protects Twitter’s right to be as specific, or as vague, as it wants in defining what constitutes “harassment,” “hateful conduct,” “violent threats,” “glorification of violence,” etc.

V. Even Rolling Back Section 230’s Immunities

Would Not Create Liability under Antitrust or Consumer Protection Law Based on the Exercise of Editorial Discretion

Current law is clear: The First Amendment bars liability under antitrust or other competition laws for content moderation. Section 230, both (c)(1) and (c)(2)(A), provide a procedural short-cut that allows defendants to avoid having to litigate cases that would ultimately fail anyway under the First Amendment—just as anti-SLAPP laws do in certain defamation cases. This Administration has tried to sidestep current law in two ways.

A. Social Media Enjoy the Same First Amendment Rights as Newspapers and Other Publishers

In a 2017 opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy called social media the “modern public square” and declared that “to foreclose access to social media altogether is to prevent the user from engaging in the legitimate exercise of First Amendment rights.”[171] Many, across the political spectrum, have cited this passage to insist that their proposed regulations would actually vindicate the First Amendment rights of Internet users.[172]

For example, the NTIA petition breezily asserts that “social media and other online platforms . . . function, as the Supreme Court recognized, as a 21st century equivalent of the public square.”[173] NTIA cites the Supreme Court’s recent Packingham decision: “Social media . . . are the principal sources for knowing current events, checking ads for employment, speaking and listening in the modern public square, and otherwise exploring the vast realms of human thought and knowledge.”[174] The Executive Order goes even further: “Communication through these channels has become important for meaningful participation in American democracy, including to petition elected leaders. These sites are providing an important forum to the public for others to engage in free expression and debate. Cf. PruneYard Shopping Center v. Robins, 447 U.S. 74, 85-89 (1980).”[175] The Executive Order suggests that the First Amendment should constrain, rather than protect, the editorial discretion of social media operators because social media are de facto government actors.

Both the Order and the Petition omit a critical legal detail about Packingham: it involved a state law restricting the Internet use of convicted sex offenders. Justice Kennedy’s simile that social media is “a 21st century equivalent of the public square” merely conveys the gravity of the deprivation of free speech rights effected by the state law. Packingham says nothing whatsoever to suggest that private media companies become de facto state actors by virtue of providing that “public square.” On the contrary, in his concurrence, Justice Alito expressed dissatisfaction with the “undisciplined dicta” in the majority’s opinion and asked his colleagues to “be more attentive to the implications of its rhetoric” likening the Internet to public parks and streets.[176]

The Executive Order relies on the Supreme Court’s 1980 decision in Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins, treating shopping malls as public fora under California’s constitution.[177] NTIA makes essentially the same argument, by misquoting Packingham, even without directly citing Pruneyard. NTIA had good reason not to cite the case: it is clearly inapplicable, stands on shaky legal foundations on its own terms, and is antithetical to longstanding conservative positions regarding private property and the First Amendment. In any event, Pruneyard involved shopping malls (for whom speech exercised on their grounds was both incidental and unwelcome), not companies for which the exercise of editorial discretion lay at the center of their business. Pruneyard has never been applied to a media company, traditional or new. The Supreme Court ruled on a very narrow set of facts and said that states have general power to regulate property for certain free speech activities. The Supreme Court, however, has not applied the decision more broadly, and lower courts have rejected Pruneyard’s application to social media.[178] Social media companies are in the speech business, unlike businesses which incidentally host the speech of others.