Introduction

Digital platforms have attracted unparalleled recent interest from antitrust and competition authorities.[1] Many digital platforms are free to consumers and are supported by advertising. Given this, the question of how advertisers approach and allocate advertising matters for understanding the potential competitive implications of digital platforms. The topic of digital advertising and competition is vast, so in this paper I focus on analyzing a very simple question-what drives advertisers to substitute across advertising venues, and what barriers might exist to an advertiser switching or substituting between advertising venues?

When there are multiple users of a platform, it is important to not approach the question of market definition and substitution simply through the lens of the consumer side of digital platforms. The recent Stigler Report on the economy[2] for example, stated that “[m]arket definition will vary according to what consumers are substituting between, whether there is competition on the platform between complements, or competition between platforms, or competition between a platform and potential or nascent competitors regarding possible future markets.” By contrast, this paper focuses on the question of how advertisers themselves approach substituting between different types of advertising.

Prior to the digital revolution, advertising was one of the most problematic parts of a firm’s marketing or overall business portfolio. In particular, it was nearly impossible for any firm to take a quantitatively-driven perspective on how successful its advertising investments were. As a result, decisions about how to allocate advertising expenditures were not generally reflective of a quantitative approach or optimized against any metric. However, in this chapter I argue that the digitization of advertising has made it one of the most quantifiable and consequently optimizable parts of spending in a firm’s marketing portfolio. This extends arguments I made in earlier work in 2013.[3]

I. Digital Transformation

There are three crucial drivers of the digital transformation of advertising: Measurement, placement, and targeting. However, most policy papers on competition in advertising markets focus only on targeting.[4]

A. Measurement

Before the digital era, firms could not measure the effectiveness of advertising. As a result, it was an unsatisfactory part of any firm’s strategy. Firms had little information about what worked and what didn’t. When talking about advertising, people love to use the quote, “Half of my advertising is wasted, the trouble is I don’t know which half.” This quote may understate the issue.[5] Recent academic research of TV ad campaigns has suggested that campaigns by over two-thirds of brands have negative or insignificant effects on sales.[6]

B. Placement

Placing ads in the digital era is much cheaper and easier. In the analog era, it required costly human interaction and was a largely manual process. Many firms hired ad agencies because agencies were able to better coordinate and reduce the costs of placing ads on television, the news media, and radio.[7] By contrast, in the digital era, the existence of ad platforms’ application programming interfaces (“APIs”) and ‘self-service’ platforms mean that human intervention is rarely needed. Of course, large firms still employ digital agencies to help them scale and deploy resources. Small firms, who previously perhaps advertised by distributing leaflets door-to-door or putting up notices in coffee shops and diners, are now able to advertise digitally because their small budgets are no longer a barrier to them being able to deploy advertising in a world where there are few ‘minimum buys’ and anyone can place an ad in minutes via a self-service platform.

C. Targeting

Targeting is important in the digital advertising economy. From an economics perspective it avoids wastage for both advertiser and consumer. Targeting allows advertisers to not waste money showing ads to people who will never be interested in their product or service, and allows consumer to only see ads for products they may be interested in.

In general, all three parts of the digital revolution in advertising are important to keep in mind when thinking about advertising markets. Advertising markets have become unrecognizable from even a decade ago. This fluidity is a central theme that should be front-and- center when trying to understand any persistent attempt at a market definition.

II. The Marketing Funnel as Lens to How Advertisers Think About Advertising

When understanding competition, it is useful to understand how a “customer” – in this case an advertiser – approaches advertising allocation decisions. To do that I elaborate on a bedrock concept in marketing theory, which is the marketing funnel.

A. What is the Marketing Funnel?

The marketing funnel, at over a century old, is one of the oldest frameworks in marketing. It describes the way that a firm can deploy marketing to address a variety of hurdles customers face if they are to purchase a new product or service. One of the earliest attempts at describing this process was in 1898, by advertising executive E. St. Elmo Lewis. Lewis described four steps through which a customer engages an advertisement, which he called AIDA: A – Attention, I – Interest of the Customer, D – Desire, and A – Action.[8] Through AIDA, an advertiser would introduce the product to the consumer, convince the consumer of their need for the product, and, ideally, sell them the product at the end of the exchange.[9]

The central insight of the marketing funnel is that an advertiser can use ads to influence a consumer at each successive stage of that consumer’s path to purchase. The funnel can be broken up broadly into three stages: The upper, middle, and lower funnel.

In the “upper funnel,” the advertiser’s main goal is to increase “Awareness” of the product or brand among potential consumers. Therefore, the advertiser’s focus is on deploying tactics that lead to awareness. The awareness stage may be relevant for new or existing brands. If customers are already aware of a brand, advertising can create the “mere exposure” effect, where repeated exposure to a brand can help prompt brand affinity.

In the “middle funnel,” the advertiser’s main goal is to ensure that customers—who are searching for different options, evaluating them, and deciding which products deserve consideration—end up considering their product in depth. In this stage, a consumer’s role is generally less passive. Consumers gather more information about particular products or services. As their preferences become more refined, consumers may introduce or eliminate products based on price, perceived quality, connection to the product or brand’s mission, or other factors. Consumers in the consideration stage look for differences in the products and may turn to customer reviews, review websites, or other digital information sources. Therefore, the advertiser’s focus is on deploying tactics which lead to “Evaluation” or “Consideration.”

In the “lower funnel,” the advertiser’s main goal is to ensure that customers who are about to purchase a product end up purchasing their product. At this point, a consumer likely has decided which product to buy, and the advertiser’s goal is to make the purchase as easy as possible. Advertisers often include incentives in this stage as well, such as a personalized coupon with a time limit, to increase the likelihood of sale. Therefore, the advertiser’s focus is on deploying tactics which lead to “Conversion.”

The marketing funnel is a canonical enough framework that academics have spent decades trying to understand its nuances. Several papers examine how the framework can be adapted for the digital age.[10] Recent research suggests that the purchase process tends to be far more iterative than earlier models assumed.[11]

B. How Did Advertisers Use the Marketing Funnel in the Analog Past?

In the past, due to the lack of data to inform decision making, the organizing principle of the marketing funnel artificially created separation in advertising budgets.

First, advertisers used the marketing funnel as a conceptual framework for determining what types of advertising were needed. In this case, the funnel was used to determine, for a particular customer segment and product, the type of advertising that was likely to be most effective given that segment’s natural path to purchase.

Advertisers deployed the marketing funnel as a way of dividing up the purpose and use of a marketing budget. For example, for a traditional brand such as Tide laundry detergent, the funnel provided a framework for distinguishing between 1) the portion of the budget that was devoted to coupons (for example, appearing in a Sunday newspaper insert), which could be thought of as influencing the “Purchase stage,” and 2) the portion of the budget that was devoted to TV and radio, which could be thought of as influencing the “Awareness stage.”

In the past, advertisers did not know how an ad influenced a consumer at a particular stage in their path to purchase. But as a rule of thumb, advertisers knew that the more engaging and storytelling the format of the ad, the more likely it was to perform well at the top of the funnel, and the more informative the ad was, the more likely the ad was to perform well further down the funnel. Therefore, it made sense to cluster ad budgets by visual appearance into “Attention-getting ad formats” and “Information-giving ad formats,” as that matched the purposes of the ad.

Historically, the difficulty of measurement meant that these budgets used to be relatively static and advertisers did not fluidly shift money between different ad budgets devoted to different types of media because they did not know enough about the contribution of each type of ad budget to overall ad return on ad spend. This may explain why, in the earliest years of the commercialized World Wide Web, marketers initially thought separately about a “Display Ad” budget and a “Search Ad” Budget. “Display” as a budget mapped on to “Awareness” or the upper funnel, and “Search” mapped on to “Evaluation” and “Purchase,” or the middle and lower funnel. Consistent with the early way that advertisers divided up or reported their ad budgets, antitrust authorities determined that there were separate markets for search ads and display ads in cases such as Google-Doubleclick.[12] This demarcation reflects that long-gone era. In what follows, I explain why such a market definition is outdated and not relevant for 2020.

III. How Does the Marketing Funnel Work in the Digital Age?

A. The Digital Transformation of the Marketing Funnel Explains Why Advertisers Are Ready to Substitute Between More Advertising Venues

The biggest shift in the use of the marketing funnel in the digital era has been in measurability. Rather than the funnel being merely a theoretical way of understanding consumer behavior, advertisers can now measure the relative effectiveness of ads placed at each stage of the funnel and measure the performance of ads along the “full funnel.” As long as an advertiser can track whether a consumer who sees an ad eventually converts, it does not matter where the consumer saw that ad or whether that ad was intended to provoke aware- ness, consideration, or purchase. What matters is the relative return on advertising spend of that ad placement: That is, relative to its price, how many profitable conversions did it lead to? Ultimately, an advertiser interested in measuring the return on its ads does not care whether or not its ads are primarily textual or primarily visual in format. Instead, it cares about the implied cost per conversion of a customer. Indeed, advertisers themselves are constantly experimenting with ad formats.

The idea that advertising media could serve multiple parts of the funnel is not new. A TV ad could arguably be directed at the “action stage” if the ad directed consumers to immediately make a call to purchase the product. A TV ad could also be an awareness ad, which simply ensured that a consumer would start to remember the positioning of a certain brand. However, what is new is that advertisers can now measure how an ad performs directly in terms of its effects on actions, rather than assuming it may perform in a certain way.

What is also new is the extent to which multiple platforms are explicitly positioning their advertising offerings as addressing the needs of advertisers throughout the entire funnel.

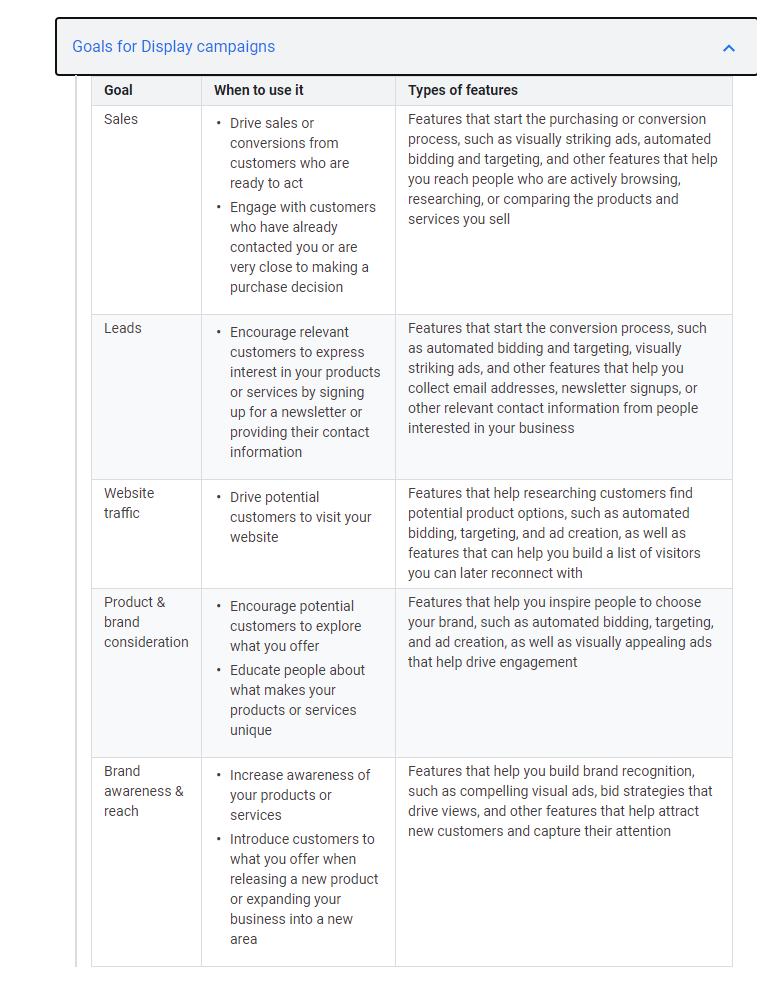

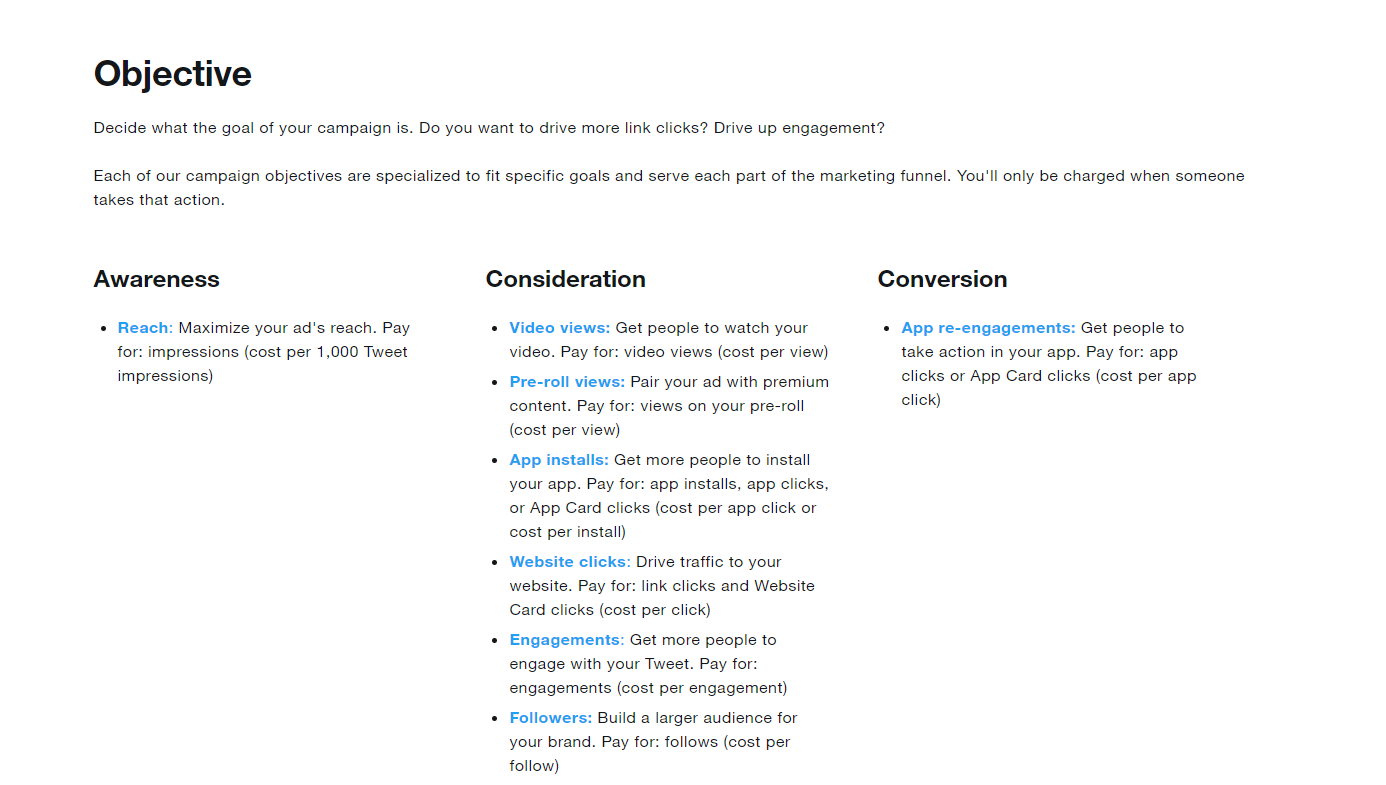

Figure 1 shows how Google presents the variety of objectives that advertisers can optimize for using its display ads. The range of objectives is very broad, spanning the upper to lower funnel. Figure 2 shows how Twitter also presents a variety of objectives. Again, it is notable both how the objectives reflect the different parts of the traditional funnel, but also the sheer extent to which Twitter positions its advertising product as covering the entire funnel. In each of these figures, several things are clear. First, the ad venue uses the language of the traditional marketing funnel to help advertisers demarcate their goals for launching a campaign on the ad venue. This language shows the continued conceptual relevance of the marketing funnel in today’s digital advertising world. Second, these ad venues allow advertisers to self-select their funnel goal and offer different measurement techniques to help advertisers determine the success of their ads. Third, these ad venues are eager to present their products as spanning the entire funnel, from upper-funnel aims, such as awareness, to lower-funnel objectives, such as conversions.

Figure 1: Google Display Ads Can Be Used for a Full Range of Funnel Objectives

Source: https://support.google.com/google-ads/answer/7450050?hl=en

Figure 2: Twitter Ads Can Be Used for a Full Range of Funnel Objectives

Source: https://business.twitter.com/en/help/account-setup/campaigns-101.html

B. The Digital Transformation of the Marketing Funnel Explains Why Advertisers Are Ready to Substitute Between More Advertising Formats

In the past, advertisers believed that in the upper funnel, because they were competing against clutter, they needed to use storytelling and highly visual formats to gain attention. A focus on engagement is why TV advertising has been historically so successful—it is the best format for engaging users and telling them the story the brand wants them to hear. However, this rule has been replaced by measurement, meaning that advertisers can effectively use any format at any place in the funnel and evaluate whether it is effective for that particular target audience. Ultimately, an advertiser is indifferent between whether it is a video ad, or a static text-laden ad that influences a customer to purchase as long as they can measure how effective that format was relative to its price.

C. Can Analog Advertising Media Compete in this New Digital Era?

One lingering question is whether or not older forms of media should be thought of as part of the market. How could something such as TV or radio compete in this new digital era? Historically, TV primarily catered to upper funnel objectives. Advertisers had limited ways of measuring ad exposure since users did not interact with TV ads and, following ad exposure, there were no methods of directly tracking a user’s activity.

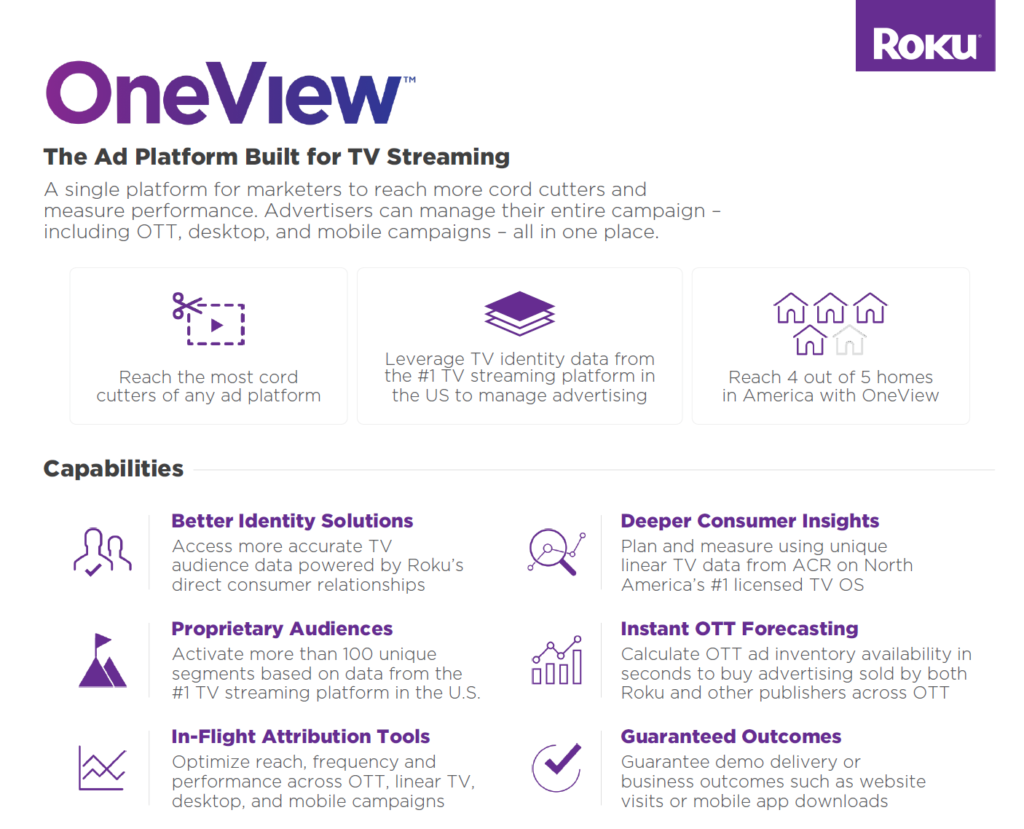

However, there is growing connectivity of television devices to the internet which has changed this. For example, a firm like Roku is able to identify who I am via my IP address, or the email address or mobile phone number I used to sign up. Roku can then use this information to evaluate whether I purchased something after being exposed to an ad, and can also use external data to identify whether I am in a target segment and should have purchased the product. Roku is a leader in propelling television advertising to be more data-driven, as shown in Figure 3, but there are growing signs of the spread of digital tools across the board in TV advertising.[13]

The growth of self-service interfaces for TV advertising promises to make TV far more accessible in the future to advertisers regardless of their size or budget.[14]

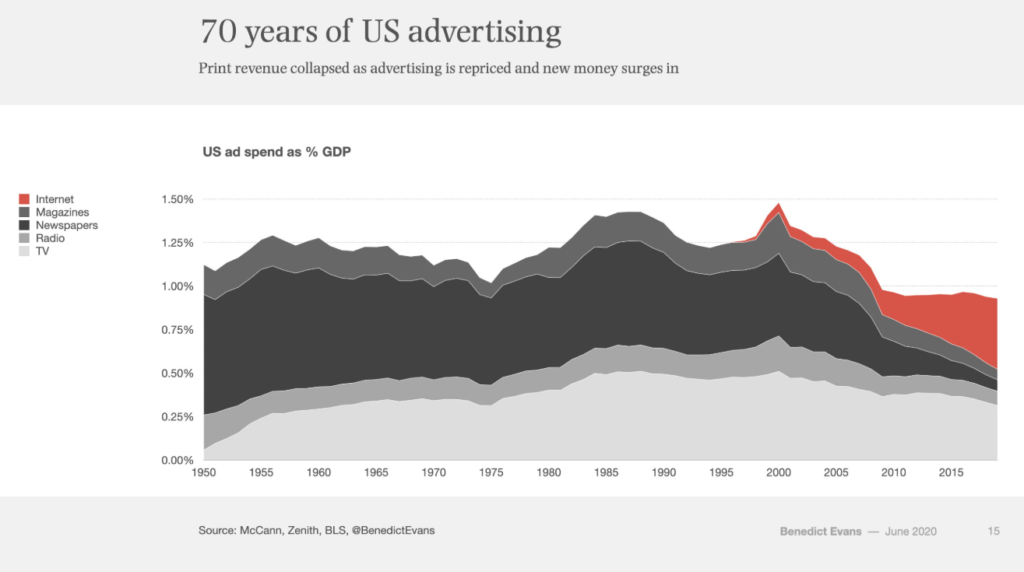

Some data on the broader topic of movements between digital advertising, television, and print may be helpful. First, Figure 4 shows how US ad spend has varied over the last 70 years. Several facts are surprising. In the past 20 years, TV and Radio have stayed surprisingly steady. Expenditure on newspaper and magazine advertising however, fell steeply starting in 2000. Since 2010, there has been a growth in spending on digital advertising, but spending overall on advertising is lower as a proportion of GDP in the last decade than at any point in the last 70 years.

Of course, spending reflects both price and quantity. In general, since advertising isn’t a widget and it is not clear how you would count quantity across different mediums, it is possible to also look at price-index shifts to try and understand the drivers of the change, and understand what quantity shifts must underlie it.

Figure 3:

Source: https://info.advertising.roku.com/Oneview_Product_Guide

Figure 4: Source: Benedict Evans Twitter Account, https://twitter.com/benedictevans/status/1271083311356674049

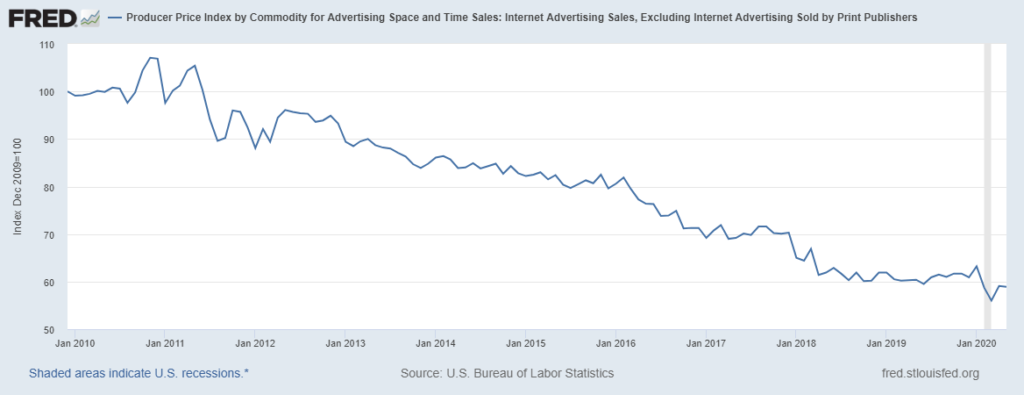

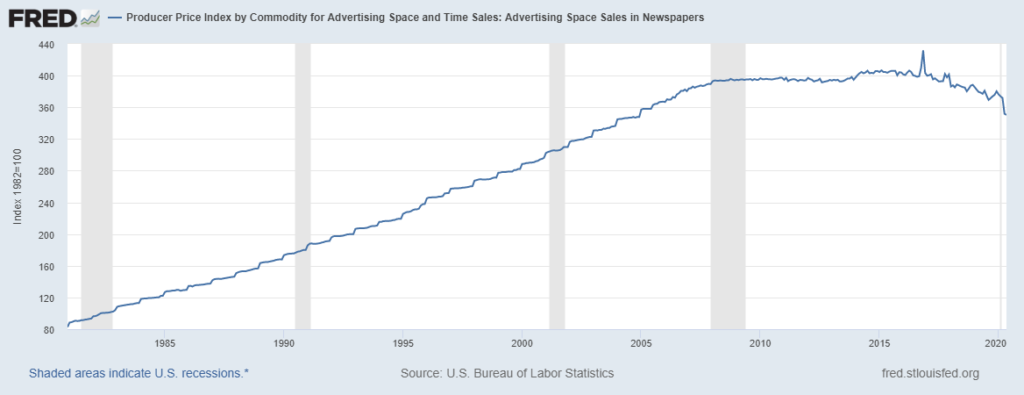

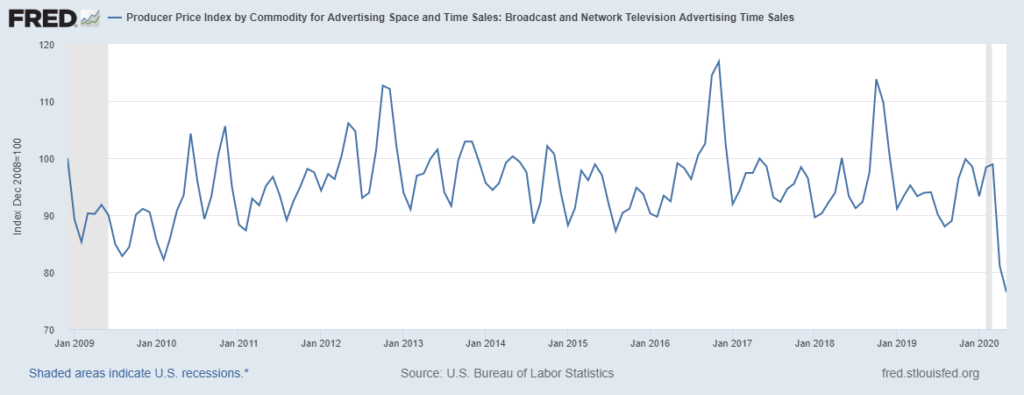

Figures 5, 6, and 7 show prices for internet, newspaper, and TV advertising as reported by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Two patterns are striking. First, that internet ad prices have fallen a great deal. Second, that newspaper and TV prices have not fallen that much. This implies that when we interpret Figure 4, the quantity of internet advertising must also have increased. Of course, the interpretation of ‘quantity’ is problematic in any advertising setting, the comparability between these time series is not clear. Further, the source of this data is survey-based. However, it is interesting that there is an indication that prices are falling in the digital ad sector, even as relatively more money is being devoted to it.

Figure 5: Internet Advertising Prices Are Falling

Source: U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics, Producer Price Index by Commodity for Advertising Space and Time Sales: Internet Advertising Sales, Excluding Internet Advertising Sold by Print Publishers [WPU365], FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WPU365 (last visited on Jun. 25, 2020)

Figure 6: Newspaper advertising prices haven’t fallen that much

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Producer Price Index by Commodity for Advertising Space and Time Sales: Advertising Space Sales in Newspapers [WPU361102], FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WPU361102 (last visited on Jun. 25, 2020)

Figure 7: TV advertising prices haven’t fallen that much

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Producer Price Index by Commodity for Advertising Space and Time Sales: Broadcast and Network Television Advertising Time Sales [WPU36210101], FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WPU36210101 (last visited Jun. 25, 2020)

D. Is There a Useful Distinction Between Integrated and Non-Integrated Ad Product?

One distinction that has been made by recent papers on the topic of antitrust in advertising markets is the distinction between “owned and operated supply” and “open supply.”[15] This is a welcome development, as much of the conversation about digital advertising markets has tended to focus on a few larger firms (such as Google, Amazon, and Facebook) and to ignore the large programmatic digital advertising sector.

One possible reason that the programmatic sector is not talked about much is that, superficially, it appears very complicated and uses a lot of confusing initials.

Programmatic advertising, for example, is made possible through the interaction of Demand Side Platforms (“DSPs”), Supply Side Platforms (“SSPs”), and Data Management Platforms (“DMPs”). Typically, an advertiser (for example GM) would use a DSP to place orders for showing ads to a particular segment of consumers, such as people who may be shopping for an automobile and who live in a particular region. The DSP would then execute these orders by connecting with an SSP that then connects to large and small websites that sell display advertising spaces. The seeming complexity of the system belies the fact that it is completely automated for the advertiser. The process is set up in a way that allows advertisers to access data about a particular user in real time.

This open system may advantage advertisers. The use of specialized intermediaries by brands to place ads through a provider such as Google enables these specialized intermediaries to pay less for access to digital advertising platforms.[16] However, antitrust authorities agree that this distinction may not be useful for thinking about substitution. For example, the CMA said “[m]edia agencies told us that similar advertising formats and audiences are available on owned-and-operated platforms and in open display advertising and that the targeting techniques available are also roughly the same.”[17] I concur. The analogy I make is that many digital ad platforms are selling an integrated product that combines eyeballs, targeting, and measurement capability. Advertisers can buy these product components separately in the programmatic display market. Given the similar digital tools underlying the integrated and non-integrated products, it stands to reason that they are potential substitutes.

1. Should we be Thinking About Substitution in Advertising or Substitution Across Marketing Communications?

When I teach marketing, one of the preconceptions I always have to dispel is that marketing communications (or marketing itself) consists solely of advertising. Instead, many effective forms of marketing communications which influence consumers’ behaviors in the funnel do not actually involve paid advertising. We distinguish three forms of reach that all have similar objectives and functionality from a marketing perspective – paid reach (such as advertising), earned reach (such as viral content), and owned reach (such as a website or white paper).

The amount of money that is spent even on paid reach outside of advertising is surprising. In 2015, for example, Pepsi spent around $370 million on sponsorships in the US.[18] US sponsorship spending in 2017 was $23.1 billion.[19] One challenge for sponsorship spending is that, much like traditional advertising, it has been hard to measure its effectiveness.[20]

In the digital era, sponsorships often take the form of “influencer marketing.” In influencer marketing, a brand pays a person who produces popular content to promote their product directly and circumvents paying the website hosting the content. Influencer marketing has grown strongly in the last 5 years, and is projected to be a $9.7 billion industry in 2020.[21] An example of this is the YouTube channel ‘Ryan’s World,’ which offers toy recommendations and has over 25.5 million subscribers and 31.8 billion lifetime views.[22] The way that influencer marketing is written about by marketers is also interesting to an economist, take this passage for example:

The Unbound Collection by Hyatt had launched the brand on the premise that the authenticity of social media content is the most powerful vehicle for not only telling the story of a non-traditional hotel brand in an unconventional way, but also the right way to connect with a target audience that takes pride in discovering hidden gems. From twitter contests to social influencer engagement campaigns, social first was the storytelling vehicle of choice for The Unbound Collection by Hyatt.

In this case, our strategy was to authentically and seamlessly connect the energy of a rising star (Dua Lipa) and an emotionally resonant story with the brand via a series of highly shareable content pieces that positioned The Confidante Miami Beach (an Unbound Collection by Hyatt hotel) as a ”co-star” in her story. After all, its inspiration and its name came from the notion of being a trusted friend.[23]

What is interesting is the idea that because it feels more authentic, influencer marketing might offer superior performance to traditional paid advertising. In any case, it illustrates that many marketers may view advertising as a substitute for many different approaches to marketing communications.

IV. What About Other Barriers to Substitution

A. Switching Costs

To think about switching costs, it is useful to think about two main potential sources of switching costs for advertisers. The first is the potential for there to be functional fixed costs, in terms of the time and expense needed to set up the first campaign, when an advertiser uses a new ad venue for the first time. The second, related set of switching costs, could be the difficulty in transporting data, campaigns, or insight from advertising venue to advertising venue.

B. Costs of Starting a New Campaign on a New Venue?

An advertiser’s ability to manage relationships with multiple ad venues is relevant to whether they consider the ad venue—and different delivery methods associated with the ad venue—to be a close substitute, because the ad venue closely shapes switching costs. The advent of self-service platforms and digital agencies has reduced the costs considerably for an advertiser of showing ads on multiple platforms.

Self-service ad platforms make the process of launching and monitoring a campaign easier and less costly for advertisers.[24] These self-service tools allow ad venues to expand their set of potential customers to include businesses with lower advertising budgets. In addition to being less costly, advertisers benefit from the additional flexibility self-service platforms provide, from the reduction or elimination of the requirement for minimum ad spend, and from the timely feedback they obtain on the performance of their ad campaigns. As a result, self-service ad platforms contribute to reducing switching costs for advertisers, thereby facilitating switching across ad platforms.

In addition, advertisers typically can set up campaigns on a demand-side platform (“DSP”) for little to no monetary cost. For example, in a matter of minutes I was able to set up an account at Reklam, a DSP based in Turkey, and access their self-service platform, in minutes.[25] Using this platform, a small advertiser can automate the creation of campaigns and easily start buying a variety of ads in a variety of ad formats, spanning video to native ads. As well as being able to place ads, an advertiser can also track their performance using a pixel. This is easy to create in their self-service interface, as shown in Figure 8.

![]()

Figure 8: Reklam’s

Source: https://www.reklamstore.com/

Until recently, traditional TV ad buying was a manual and time-consuming process that often involved large upfront buys. TV providers have developed self-service platforms simplifying the TV ad buying process and making it easier for advertisers to potentially switch to using their services. For example, Comcast’s self-service ad portal allows advertisers, even small businesses, to purchase TV ads for as little as a few hundred dollars a month. Other providers, such as Charter Communications, also have self-serve platforms. By reducing minimum ad-buy requirements and setup costs, these services increase advertisers’ ability to multi-home.

C. Costs of Switching Campaigns Across Ad Venues

Innovations automating campaign creation and management also streamline ad creation and delivery, reducing the amount of effort needed by advertisers. This flexibility decreases switching costs across platforms by helping advertisers automatically create different ad formats, and automates the delivery of high-performing combinations of their creative assets to audiences.

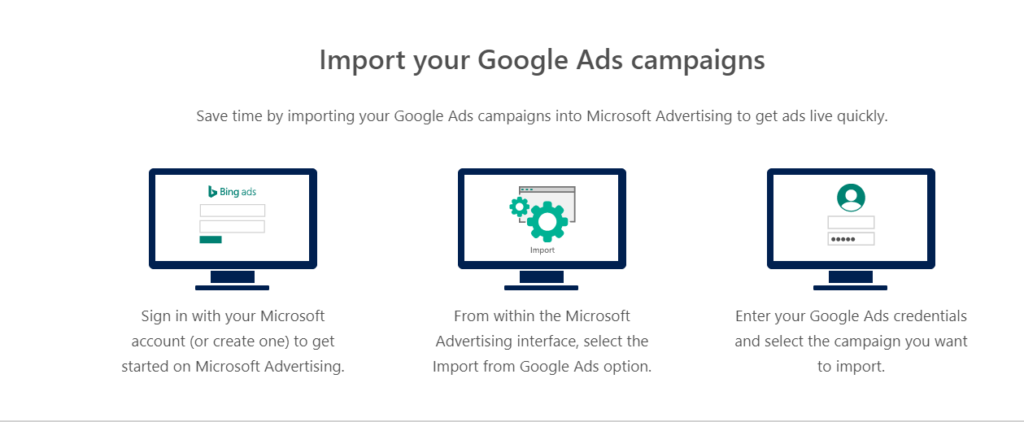

A useful example of this is the Bing import ads tool displayed in Figure 9, which allows advertisers to easily import campaign settings and keywords from Google ads.

Figure 9: Bing Ads makes it easy to import quickly settings from Google ads

In general, the importance of standardizing ad format in understanding digital advertising markets is something I have highlighted in my own research.[26] The process of standardization of ad format increases flexibility across ad format. However, increasingly, digital tools have emerged that automate the entire process of setting up and managing a campaign at a very low fixed cost. For example, firms like Promo allow firms to create effective video ads in less than five minutes.[27]

D. Network Effects

Advertisers do choose to launch advertising campaigns on the basis of the potential number and also the type of consumers they can reach. In the early days of online advertising, venues such as Yahoo! and ESPN were uniquely valuable online properties, because they attracted so many users. If an advertiser was interested in emulating online the mass reach of an ad shown during the TV show “Friends,” these properties were attractive venues. However, as digital advertising has evolved, there is now less need to use a single website as a venue. Instead, advertisers can achieve similar reach by using programmatic advertising and buying an audience across multiple websites.

Advertisers may or may not care about “reach,” or sheer number of eyeballs, in a world where targeting or even micro-targeting is emphasized. In the academic literature, we acknowledge this tension as a ‘reach-relevance’ tradeoff in choosing advertising venues. However, the programmatic advertising revolution has reduced the importance of this tradeoff. Using the programmatic ecosystem, advertisers can show an ad to people in a large audience segment across multiple websites. In other words, programmatic advertising eliminates the need to go to a single large ad venue to achieve reach.

E. Data

1. What Kind of Data is Used in Advertising?

There is a tendency to treat all data as equal for the purposes of antitrust analysis of advertising markets.[28] Therefore, it is useful to distinguish between different labels that advertisers use to categorize data.

First, advertisers can use “declared data.” These are data that a user self-reports to a website. For example, I might enter my home zip code when I first engage with a website. If a small business near my home then uses that home zip code to target ads towards me that they think might interest me, then that would be an example of targeting based on “declared data.”

Second, advertisers can use “observed data.” These data are a collection of observed behavior. They may include, for example, data on the operating system of my Android cell phone. They could also include data on the location of my cell phone if I have opted into location tracking. If an advertiser targeted a price comparison app ad to me because I am an Android user who frequently visits toy stores, that would be an example of targeting based on observed data.

Third, advertisers can use “inferred data.” These are data where a user’s actual preferences are inferred from the user’s actions. Such data are particularly useful for understanding whether a user is ”in market” for a certain product. For example, a valuable segment based on ”inferred data” are ”auto intenders.” Here, the type of content that a user browses is collected – for example, do they go to websites like Edmunds.com? – and predictions are made about whether the person is likely to buy an automobile in the near future. Typically, such predictions are made using some form of prediction algorithm. This prediction task is complicated by the fact that there are many products that have relatively short purchase cycles where consumers are only likely to be influenced by ads for a short time window. For example, if I am thinking of buying my mother flowers for Mother’s Day, then there are only probably a few hours where ads are likely to be effective at influencing which website I order from.

Firms have developed ways of collating and integrating data about consumers from a variety of sources. These include data that they own (“first-party” data), data they have an agreement to share with another website (“second-party” data), and data they buy from a third-party (“third-party” data). Broadly, DMPs allow advertisers to combine and store this data about users from a variety of different sources. DMPs synchronize data about a user and allow advertisers to determine whether or not the user is indeed, for example, shopping for a vehicle and living in the right place.

2. “Economies of Scale or Scope” Does Not Appear to be the Right Lens

In advertising markets, data are an input, and the key output is the accuracy of predicting a user’s interest in an advertised product or service. The relevant question for understanding whether or not data can help reinforce any incumbency advantage is establishing whether and, if so, at what point there are diminishing returns to the predictive power of data. In general, the literature suggests that diminishing returns to prediction appear swiftly.

Recent research measured the value of data for prediction using Amazon data. They showed that there are returns to data size (albeit with diminishing returns) with respect to demand prediction accuracy over time for a single product.[29] However, they also showed that there are small gains to demand prediction accuracy across products as data size increases. Another paper showed that the largest gain to increased data size of search engine logs is between approximately zero and 500 sessions, after which point the incremental returns to more data are decreasing.[30]

Similarly, researchers have found decreasing economic returns to data in the context of algorithmic recommendations in news. Recent research explored the performance of an automated recommendation versus a human-curated search result in terms of user engagement (clicks).[31] In particular, they tested how this relationship changes as the algorithm has access to more data about the searcher’s previous visits. The study found little increase in algorithmic predictive accuracy from increasing the span of data from six to 200 visits, but did find a large increase in predictive accuracy when the platform has data on six visits rather than two visits.

These findings are consistent with my own research where I showed that prediction accuracy for demographic variables such as age and gender did not change with the amount of data available.[32] In another paper, I found that a reduction in the amount of data that search engines stored about their users due to changes in EU regulations did not affect the ability of the search engines to identify relevant results for their users.[33]

One limiting constraint on the value of incremental data is the potential for spurious correlations. In essence, the downside of more statistical precision is that often this statistical precision can identify a correlation that does not reflect a true causal relationship. Therefore, much of the value from having access to large data sets primarily comes from experimentation. Such experimentation often requires only a small amount of data to identify causal relationships. For example, eBay was able to identify return on investment for its search advertising investments using a relatively short time span and amount of data.[34]

An alternative argument for why the size of data might matter, is that larger datasets are more likely to allow the combination of different pieces of data. In general, the academic evidence on this possibility is not strong. For example, Matz et al. (2019) suggests a small incremental value of combining different types of data.[35]

3. Can Data be a Unique Source of Comparative Advantage?

Some academics have argued that data may act as an essential facility, which might prevent or hinder entry by firms. A classic example of an essential facility is an instance where a railroad company controlled the only bridge across the Mississippi river. An essential facility remedy would require such a monopolist to allow others to use the bridge at a fair rate. However, in general, uncontested examples of an essential facility are rare, because an essential facility must be unique, valuable, and inimitable.

The argument is somewhat complex in the case of data because it is not the data that may potentially constitute an essential facility, but the insights provided by the data about any one consumer. Therefore, I suggest reframing the question around whether insights from the data are likely to be valuable, unique, and inimitable.

The breadth of a consumer’s footprint generally limits the uniqueness of data in the digital realm. For example, if I were buying a bicycle, I might check out listings on Facebook Marketplace, look at reviews of bicycles on www.bicycling.com, or find attractions on Tripadvisor where cycling is mentioned. As I travel to the bicycle store, I might search for directions on my smartphone and my location would be recorded by any mobile apps I have installed that track my location. Once at the store, my spending would be recorded by my credit card company, and any data brokers the credit card company shares data with. I might then post about my purchase on social media accounts or upload photos. The point of this example is that any activity I engage in generates a lot of data about an individual. These data would give many firms – at the minimum – the insight that I was the kind of per- son who enjoys cycling-oriented activities and therefore that I might be a reasonable target for ads about cycling accessories or other fitness-oriented equipment and experiences in the future.

Examples where only one digital firm or platform has access to unique insights are unusual. If a tree in my garden falls, damaging my roof, my rush to immediately identify an emergency roofer might lead me to interact only with one platform like angieslist.com, or one website like http://www.farinaroof.com/—my local roofer—or a search engine. However, most purchasing processes are more complex and involve the use of multiple digital touchpoints, from which many firms will be able to draw insights.

The larger the purchase, the more time and research will go into that decision, and the more data are generated and spread. For example, suppose that I were lucky enough to be researching private school options for my kids. Typically, such a process would take months. I might use a website like GreatSchools as my primary search tool for identifying suitable schools, but due to the length of time the decision would take, many other firms would also have the opportunity to have that insight. For example, I might post my intention of finding a new school on social media, or join groups for fans of those schools. I might install apps on my phone that allow me to evaluate schools, and my phone’s apps would also track the fact of my visiting any schools. I also might search for a school consultant. Through this process, each of these different digital venues gains insights into the consumer’s intentions.

V. Implications

This paper has discussed how digitization and its revolutionary effects on the ability of advertisers to measure has changed the marketing funnel for advertising. The focus of my discussion has been on the implications this has for market definition – both in terms of broadening the scope of substitution patterns across different ad venues and reducing switching costs for advertisers.

However, I will conclude with the following provocative thought. In general, the measurement revolution has had far broader effects than the broadening of potential market definition in advertising that I discuss in this paper. Instead, it has led to a revolution in terms of how advertisers operate, how much money advertisers can save on their advertising by avoiding spending money on unsuccessful campaigns, and allowed new business models, such as direct-to-consumer businesses, to thrive. As of yet, we have very little documentation of the benefits of this revolution, but without this documentation, discussions about the tradeoffs implied by the use of data and digital tools in the digital advertising ecosystem are being conducted in a vacuum.

Footnotes

* Catherine Tucker is the Sloan Distinguished Professor of Management Science at MIT Sloan School of Management. She has consulted for many technology companies—please see https://mitmgmtfaculty.mit.edu/cetucker/disclosure/.

[1] Competition & Markets Authority, Online Platforms and Digital Advertising: Market Study Final Report

(Jul. 1, 2020), https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/online-platforms-and-digital-advertising-market-study (hereinafter “CMA Report”); Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, Digital Platforms Inquiry: Final Report (Jun. 2019), https://www.accc.gov.au/publications/digital-platforms- inquiry-final-report.

[2] Stigler Center, Stigler Committee on Digital Platforms Final Report (Sept. 2019) (hereinafter “Stigler Report”), available at https://www.chicagobooth.edu/-/media/research/stigler/pdfs/digital-platforms—committee-report—stigler-center.pdf.

[3] Catherine Tucker, The Implications of Improved Attribution and Measurability for Antitrust and Privacy in Online Advertising Markets, 20. Geo. Mason L. Rev. 1025 (2013).

[4] For example, the Stigler Report only refers to measurement in the context of measuring the value of news. See, Stigler Report, supra note 2. On the other hand, targeting is a crucial plank of the Stigler Report’s discussion in, “An Economic Perspective on the Digital Market Structure.”

[5] This quote is often ascribed to John Wanamaker, an early pioneer in department stores. However, the historical accuracy of it is not clear and the quote has also been ascribed to many others. See, e.g., Variations on the “But We Don’t Know Which Half” Line, Terry Gray Blog, available at https://staff.washington.edu

/gray/misc/which-half.html (last visited on Nov. 22, 2019).

[6] See Bradley Shapiro, Gunter J. Hitsch, & Anna Tuchman, Generalizable and Robust TV Advertising Effects (working paper, Aug. 5, 2020), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3273476. Studies of online advertising suggest small effects on purchase intent. See Avi Goldfarb & Catherine E. Tucker, Online Display Advertising: Targeting and Obtrusiveness, 30 Mktg. Sci. 389-404 (2011).

[7] Alvin J. Silk & Ernst R. Berndt, Scale and Scope Effects on Advertising Agency Costs, 12 Mktg. Sci. 53-72 (1993).

[8] Thomas E. Barry & Daniel J. Howard, A Review and Critique of the Hierarchy of Effects in Advertising, 9 Int’l J. Advert. 121 (1990).

[9]AIDA, Oxford Reference, available at https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.

20110803095432783 (last visited Aug. 7, 2020).

[10] See, e.g., Mark Ritson, Mark Ritson: If you Think the Sales Funnel is Dead, You’ve Mistaken Tactics for Strategy, Mktg. Week (Apr. 6, 2018), https://www.marketingweek.com/mark-ritson-if-you-think-the-sales-funnel-is-dead-youve-mistaken-tactics-for-strategy/.

[11] Demetrios Vakratsas & Tim Ambler, How Advertising Works: What Do We Really Know?, 63 J. Mktg. 26 (1999).

[12] Statement of the Federal Trade Commission Concerning Google/Doubleclick, FTC File No. 071-0170 (Dec. 20, 2017), available at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/418081/071220googlec.-commstmt.pdf.

[13] For an idea of all the firms innovating in this space see Convergent TV LUMAscape, LUMA https://lumapartners.com/content/lumascapes/convergent-tv-lumascape/ (last visited on Aug. 7, 2020).

[14] See, e.g., Effectv Ad Planner, Comcast, https://adplanner.effectv.com/ (last visited Aug. 7, 2020), (a self-service marketing tool from Comcast).

[15] Competition & Markets Authority, Online Platforms and Digital Advertising: Market Study Preliminary Report at 5.21 (Dec. 18, 2019) (“Total spend in display advertising was worth £5.1 billion in the UK in 2018. About 60% of expenditure is made on owned and operated platforms, which typically provide social media to consumers.”).

[16] Francesco Decarolis & Gabriel Rovigatti, From Made Men to Maths Men: Concentration and Buyer Power in Online Advertising (CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP13897, July 2019), available at https://ssrn.

com/abstract=3428421.

[17] CMA Report, supra note 1, at ¶ 5.23.

[18] ESP Properties, Top Sponsors Report: The Biggest Sponsorship Spenders 3, available at http://www.sponsorship.com/IEG/files/81/81197cea-4a0c-4c50-a395-947480bbc3e9.pdf (last visited on Aug. 8, 2020).

[19] IEG Sponsorships.com, What Sponsors Want and Where Dollars Will Go in 2018 2, available at http://www.sponsorship.com/IEG/files/f3/f3cfac41-2983-49be-8df6-3546345e27de.pdf (last visited Aug. 8, 2020).

[20] The Marketing Accountability Standards Board is working hard to change this. See Sponsorship Accountability Part 5: Measurement, Mktg. Accountability Standards Bd. (Dec. 11, 2019), https://themasb.org/sponsorship-accountability-part-5-measurement/ (last visited on Aug. 8, 2020).

[21] Influencer MarketingHub, The State of Influencer Marketing 2020: Benchmark Report (Mar. 1, 2020), available at https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-benchmark-report-2020/ (last visited Aug. 8, 2020).

[22] Ryan’s World, YouTube, available at https://www.youtube.com/channel/UChGJGhZ9SOOH

vBB0Y4DOO_w (last visited on Oct. 15, 2020).

[23] Dua Lipa’s New Rules Music Video, The Confidante Miami Beach Part of the Unbound Collection by Hyatt, Shorty Awards, available at https://shortyawards.com/10th/dua-lipa-new-rules (last visited Oct. 15, 2020).

[24] See, e.g., @ralfonsi, Twitter Self-Service Advertising Now Available in 11 New Countries Throughout Europe, Latin America, Twitter Blog (Sep. 4, 2014), https://blog.twitter.com/en-us/a/2014/twitter-self-service-advertising-now-available-in-11-new-countries-throughout-europe-lantin-0.html.

[25] ReklamStore, available at https://www.reklamstore.com

[26] Avi Goldfarb & Catherine E. Tucker, Standardization and the Effectiveness of Online Advertising, 61 Mgmt. Sci. 2707 (2015).

[27] Create Video Ads in Minutes, Promo, available at https://promo.com/cat/create-video-ads-2s/ (last visited on Aug. 8, 2020).

[28] The CMA did try to distinguish between different types of data in Appendix F of its July 2020 CMA Report. See CMA Report, supra note 1, at Appendix F. However, the taxonomy may unnecessarily distinguish “search data” and “contextual data” from “observed data.”

[29] Patrick Bajari, et al., The Impact of Big Data on Firm Performance: An Empirical Investigation (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Res.., Working Paper No. 24334, Feb. 2018), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w24334.pdf.

[30] Maximilian Schaefer & Geza Sapi, Data Network Effects: The Example of Internet Search (Berlin Sch. of Econ., Dec. 4, 2019), available at https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Data-Network-Effects%3A-The-Example-of-Internet-Sch%C3%A4fer-Sapi/e1edbb56b709de3039e4863c8f2ff421da648b75?p2df.

[31] Jörg Claussen, Christian Peukert, & Ananya Sen, The Editor vs. the Algorithm: Economic Returns to Data and Externalities in Online News (CESifo, Working Paper No. 2364-1428, Nov. 12, 2019), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3479854.

[32] Nico Neumann, Catherine E. Tucker, & Timothy Whitfield, Frontiers: How Effective is Third-Party Consumer Profiling? Evidence from Field Studies, 38.6 Mktg. Sci. 918-926 (2019).

[33] Lesley Chiou and Catherine Tucker, Search Engines and Data Retention: Implications for Privacy and Antitrust (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Res., Working Paper No. 23815, Sep. 2017), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w23815.pdf?sy=815

[34] Blake Thomas, Chris Nosko, & Steven Tadelis, Consumer Heterogeneity and Paid Search Effectiveness: A Large-Scale Field Experiment, 83 Econometrica 155 (2015).

[35] Sandra C. Matz, et al., Predicting Individual-Level Income from Facebook Profiles, 14 PloS One (Mar. 28, 2019), https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0214369.