Introduction[1]

Legal decision-making and enforcement under uncertainty are always difficult and always potentially costly. The risk of error is always present given the limits of knowledge, but it is magnified by the precedential nature of judicial decisions: an erroneous outcome affects not only the parties to a particular case, but also all subsequent economic actors operating in “the shadow of the law.”[2] The inherent uncertainty in judicial decision-making is further exacerbated in the antitrust context where liability turns on the difficult-to-discern economic effects of challenged conduct. And this difficulty is still further magnified when antitrust decisions are made in innovative, fast-moving, poorly-understood, or novel market settings—attributes that aptly describe today’s digital economy.

Rational decision-makers will undertake enforcement and adjudication decisions with an eye toward maximizing social welfare (or, at the very least, ensuring that nominal benefits outweigh costs).[3] But “[i]n many contexts, we simply do not know what the consequences of our choices will be. Smart people can make guesses based on the best science, data, and models, but they cannot eliminate the uncertainty.”[4] Because uncertainty is pervasive, we have developed certain heuristics to help mitigate both the direct and indirect costs of decision-making under uncertainty, in order to increase the likelihood of reaching enforcement and judicial decisions that are on net beneficial for society. One of these is the error-cost framework.

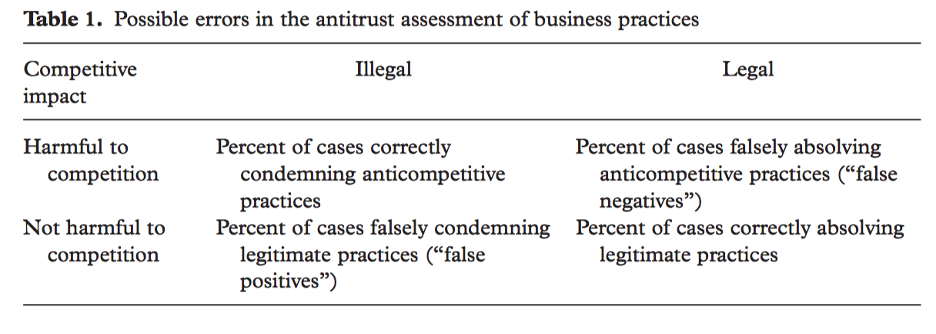

In simple terms, the objective of the error-cost framework is to ensure that regulatory rules, enforcement decisions, and judicial outcomes minimize the expected cost of (1) erroneous condemnation and deterrence of beneficial conduct (“false positives,” or “Type I errors”); (2) erroneous allowance and under-deterrence of harmful conduct (“false negatives,” or “Type II errors”); and (3) the costs of administering the system (including the cost of making and enforcing rules and judicial decisions, the costs of obtaining and evaluating information and evidence relevant to decision-making, and the costs of compliance).

In the antitrust context, a further premise of the error-cost approach is commonly (although not uncontroversially[5]) identified: the assumption that, all else equal, Type I errors are relatively more costly than Type II errors. “Mistaken inferences and the resulting false condemnations ‘are especially costly, because they chill the very conduct the antitrust laws are designed to protect.’”[6] Thus the error-cost approach in antitrust typically takes on a more normative objective: a heightened concern with avoiding the over-deterrence of procompetitive activity through the erroneous condemnation of beneficial conduct in precedent-setting judicial decisions. Various aspects of antitrust doctrine—ranging from antitrust pleading standards to the market definition exercise to the assignment of evidentiary burdens—have evolved in significant part to constrain the discretion of judges (and thus to limit the incentives of antitrust enforcers) to condemn uncertain, unfamiliar, or nonstandard conduct, lest “uncertain” be erroneously identified as “anticompetitive.”

The concern with avoiding Type I errors is even more significant in the enforcement of antitrust in the digital economy because the “twin problems of likelihood and costs of erroneous antitrust enforcement are magnified in the face of innovation.”[7] Because erroneous interventions against innovation and the business models used to deploy it threaten to deter subsequent innovation and the deployment of innovation in novel settings, both the likelihood and social cost of false positives are increased in digital and other innovative markets. Thus the avoidance of error costs in these markets also raises the related question of the proper implementation of dynamic analysis in antitrust.[8]

I. The Error-Cost Framework

A. Uncertainty, Ignorance, and Evolution

Uncertainty in the context of statistical decision theory[9] (from which error-cost analysis is derived) implies more than merely risk.[10] Risk implies that the potential outcomes are known, but that they occur only with a certain probability. Maximizing benefits (minimizing error) under these conditions is fairly straightforward, and readily reducible to a mathematical formula.

Under uncertainty, the possible consequences (costs) of a decision are known, but not the likelihood of any given outcome. This presents a much more difficult maximization problem for which judgment (flawed as it is) is required. It is also, unfortunately, far more common, as probabilities are rarely known with any degree of precision.

More troublingly, however, a disturbingly large share of the time in judicial decision-making we know neither the probabilities nor the consequences of decisions. “In such cases the uncertainty . . . is even more daunting than uncertainty in decision theory’s technical sense; it is in fact a deep form of ignorance.”[11]

Antitrust decision-making is most commonly undertaken in this state of ignorance. The stark reality for most antitrust adjudication is that the same conduct that could be beneficial in one context could be harmful in another.[12]

But it is virtually never known what the likelihood of either outcome is in the case of novel business conduct (i.e., the sort that makes its way to litigation).[13] To make matters worse, the magnitudes of the potential harm (if anticompetitive) and benefits (if procompetitive) are also essentially never knowable: in the best-case scenario the estimation of effects must be cabined to render evaluation remotely tractable, and inevitably static estimates will miss broader (and potentially more significant) dynamic effects.[14]

A further complication is the precedential nature of judicial decisions:

[I]n contrast to private decision makers, courts also have concerns about optimal deterrence. That is because a decision by a court will not only bind the litigation parties, but will also serve as precedent by which future conduct will be judged. In antitrust, for example, over-deterrence might involve deterring welfare enhancing cooperation or innovations by firms that fear a finding of liability even when their conduct does not reduce consumer welfare.[15]

The consequences of erroneous decision-making are thus considerably more significant than even the already curtailed estimates in any given case. As the Microsoft court put it:

Whether any particular act of a monopolist is exclusionary, rather than merely a form of vigorous competition, can be difficult to discern: the means of illicit exclusion, like the means of legitimate competition, are myriad. The challenge for an antitrust court lies in stating a general rule for distinguishing between exclusionary acts, which reduce social welfare, and competitive acts, which increase it.[16]

The case-by-case, common-law approach to antitrust is itself a form of error-cost avoidance. It is well known that specification of detailed, ex ante rules will ensure costly, erroneous outcomes where conduct is not clearly harmful, our understanding of its effects is indeterminate, or technological change alters either the effects of certain conduct or our understanding of it: “An important cost of legal regulation by means of rules is thus the cost of altering rules to keep pace with economic and technological change.”[17]

By contrast,

[o]bsolescence is not so serious a problem with regulation by standard. Standards are relatively unaffected by changes over time in the circumstances in which they are applied, since a standard does not specify the circumstances relevant to decision or the weight of each circumstance but merely indicates the kinds of circumstance that are relevant.[18]

Despite occasional assertions to the contrary, it is clear that the antitrust laws were drafted as imprecise standards, necessarily leaving to the courts the job of more detailed rulemaking. In this it reflects a common and well-understood legislative choice:

The legislature’s choice whether to enact a standard or a set of precise rules is implicitly also a choice between legislative and judicial rulemaking. A general legislative standard creates a demand for specification. This demand is brought to bear on the courts through the litigation process and they respond by creating rules particularizing the legislative standard.[19]

The cost of this approach, however, is that deterrence by standard is less effective, and administration more expensive. At the same time, however, the common-law approach is readily amenable to Bayesian updating, and as more information is gleaned (both through experience and the development of economic science), the common law approach incorporates it into the analysis—first through the basic operation of stare decisis, but also through concrete doctrinal changes that can amplify particular circumstances to more general cases. In this way, the process of antitrust adjudication develops along with economic learning to reduce the risk of error as more information is available.[20]

B. The Basics of Error-Cost Analysis

The application of decision theory to judicial decision-making seems to have originated with Ehrlich and Posner’s 1974 article, An Economic Analysis of Legal Rulemaking:

The model is based on a social loss function having, as its principal components, the social loss from activities that society wants to prevent, the social loss from the (undesired) deterrence of socially desirable activities, and the costs of producing and enforcing statutory and judge-made rules, including litigation costs. Efficiency is maximized by minimizing the social loss function with respect to two choice variables, the number of statutory rules and the number of judge-made rules.[21]

There the particular focus was on the specificity of legal proscriptions and the choice between standards and rules: “a theory of the legal process according to which the desire to minimize costs is a dominant consideration in the choice between precision and generality in the formulation of legal rules and standards.”[22]

Professors Joskow & Klevorick introduced decision-theoretic analysis to antitrust in their development of a framework for assessing predatory pricing.[23] As they note, uncertainty is inherent in the assessment of predatory pricing (although the same assessment applies to a great deal of antitrust analysis, much of which is similarly forward looking, and all of which is tasked with inferring anticompetitive effect from limited information):

Such an enterprise, no matter how carefully it is done, is inherently uncertain and involves the possibility of error both because the actual effects of any kind of observable short-run behavior on long-run outcomes are themselves uncertain and because our methods of predicting those effects are imperfect.[24]

The decision-theoretic framework employed by Joskow & Klevorick to assess the propriety of a general rule applicable to predatory pricing cases

directs that we choose the policy that would minimize the sum of the expected costs of error and the costs of implementation that would result if the policy were applied to the market we are considering. . . . [O]ur decision-theoretic evaluative mechanism reveals that no single rule will be best for all market situations; if a predatory pricing rule is formulated with one particular market in mind, we cannot be sure that it should be applied to other market situations.[25]

It was Judge Frank Easterbrook who generalized the approach for antitrust, and offered the clearest exposition of the error-cost approach:[26]

The legal system should be designed to minimize the total costs of (1) anticompetitive practices that escape condemnation; (2) competitive practices that are condemned or deterred; and (3) the system itself.[27]

The role of presumptions and other doctrinal elements of the process of antitrust review—“filters” in Easterbrook’s terminology—is central to the effectuation of the error-cost framework:

The third is easiest to understand. Some practices, although anticompetitive, are not worth deterring. We do not hold three-week trials about parking tickets. And when we do seek to deter, we want to do so at the least cost. A shift to the use of presumptions addresses (3) directly, and a change in the content of the legal rules influences all three points. . . .

. . . The task, then, is to create simple rules that will filter the category of probably-beneficial practices out of the legal system, leaving to assessment under the Rule of Reason only those with significant risks of competitive injury.[28]

Error-cost analysis applies a Bayesian decision-theoretic framework designed to address problems of decision-making under uncertainty. In antitrust, decision-makers are tasked with maximizing consumer welfare.[29] The problem, of course, is that it is never clear in any given case—particularly those that make their way to actual litigation—what decision will accomplish this objective.[30]

Given this uncertainty, we can recharacterize the effort to maximize consumer welfare in antitrust decision-making as an effort to minimize the loss of consumer welfare from (inevitably) erroneous decisions.[31] The likelihood of error decreases with additional information, but there is a cost to obtaining new information. So, the error-cost framework seeks to minimize error for a given amount of information as well as to determine what amount (and type) of information is optimal.

In evaluating investment in information, the benefit of additional information is that it may reduce the likelihood of making a costly erroneous decision. In this sense, the decision to consider additional information can be seen as a tradeoff between two types of costs—error costs on the one hand and information costs on the other. A rational decision maker will try to minimize the sum of the two types of costs. This is the second key insight of the decision theoretic approach.[32]

Crucial to the application of the error-cost framework in the judicial or regulatory context is that the costs (benefits) of an erroneous (correct) decision are not limited to the immediate consequences of the conduct at hand. Because judicial determinations establish precedent, and because regulatory rules are applied broadly, antitrust decision-makers must also consider the risk and cost of over- and under-deterrence resulting from erroneous decisions.[33] These dynamic, long-term consequences of antitrust decision-making are likely the most significant source of cost from erroneous decisions.

Applying this approach, the decision-maker (e.g., regulator, court, or legislator) holds a relatively uninformed prior belief about the likelihood that a particular business practice is anticompetitive. These prior beliefs are updated either with new knowledge as the theoretical and empirical understanding of the practice evolves over time, or with new evidence specific to the case at hand. Knowledge regarding the likely competitive effects of business conduct is never perfect, but each additional piece of information may improve the likelihood of accurately predicting whether the conduct is harmful or not (although obtaining it may be costly, and it also may increase the cost of accurate decision-making). The optimal decision rule is based on the updated likelihood that the practice is anticompetitive by minimizing a loss function measuring the costs of Type I and Type II errors.

The key policy tradeoff is between Type I (“false positive”) and Type II (“false negative”) errors. Table 1 presents a two-by-two matrix laying out the types of errors that occur in antitrust litigation.[34]

Easterbrook’s operationalization of the framework entails three key, underlying assumptions:[35]

- Both Type I and Type II errors are inevitable in antitrust cases because of the difficulty in distinguishing efficient, procompetitive business conduct from anticompetitive behavior;

- The social costs associated with Type I errors are generally greater than the social costs of Type II errors because market forces offer at least some corrective with respect to Type II errors and none with regard to Type I errors: “the economic system corrects monopoly more readily than it corrects judicial [Type II] errors;”[36] and

- Optimal antitrust rules will minimize the expected sum of error costs subject to the constraint that the rules be relatively simple and reasonably administrable.[37]

The inevitability of errors in antitrust cases is a function of two related, but distinct, knowledge problems. The first is rooted in the limits of the underlying economic science which provides the guidance by which decisionmakers attempt to identify anticompetitive conduct and specify the rules relating to that conduct. Because economic science is constantly evolving (to say nothing of inherently imperfect) and imperfectly translated into judicial decision-making, rules will always be imperfectly specified.[38] Economists, who supply the crucial input of economic science, tend not to advance their analyses in realistic institutional settings (in part a function of the need for simplification in economic models to ensure their tractability) and thus regularly “avoid incorporating the social costs of erroneous enforcement decisions into their analyses and recommendations for legal rules.”[39] They also have divergent incentives and ulterior motives that may make them less likely to do a good job.[40] Meanwhile, lawyers, judges, and enforcers, for their part, are often limited in their ability to apply the relevant economic science to complicated and imperfect facts, and to adduce the optimal legal rules.[41] The net result is that it is a fundamentally difficult task to identify illegal, anticompetitive conduct and distinguish it from legal, procompetitive conduct in any specific case:

The key point is that the task of distinguishing anticompetitive behavior from procompetitive behavior is a herculean one imposed on enforcers and judges, and that even when economists get it right before the practice is litigated, some error is inevitable. The power of the error-cost framework is that it allows regulators, judges, and policymakers to harness the power of economics, and the state-of-the-art theory and evidence, into the formulation of simple and sensible filters and safe-harbors rather than to convert themselves into amateur econometricians, game-theorists, or behaviorists.[42]

The second knowledge problem leading to the inevitability of errors stems from the lack of precision in legal rules generally. As Easterbrook notes, “one cannot have the savings of decision by rule without accepting the costs of mistakes.”[43] Because the application of economic science to any given situation is imperfect, comprehensive proscriptions cannot often be specified in advance. At the same time (and for much the same reason), the case-by-case, ex post determination of antitrust liability through the rule of reason process is costly and difficult to administer accurately. The result is that there are relatively few simple rules (e.g., safe harbors and per se rules) in place: where there aren’t, adjudication is costly and imperfect; where there are, errors are inevitable.

C. The Implementation of the Error-Cost Framework in Antitrust Adjudication

The knowledge problem confronting antitrust decisionmakers is somewhat ameliorated by the imposition of intermediate, simplifying procedures that impose categorization and filters at various stages in the process to improve the efficiency of decision-making given the cost of litigation (including, e.g., time costs, burdens on judicial resources, and discovery costs). Standing rules, for example, are classic error-cost minimization rules. The availability of standing turns on certain indicia that correlate with the expected likelihood that a plaintiff in a given position will have a justiciable case. Where that likelihood is identifiably low, it is more efficient to curtail adjudication before it even begins by denying standing, even though occasionally this will erroneously prevent the adjudication of meritorious cases.

At the overarching, substantive level, the choice between, on the one hand, engaging in a full-blown rule of reason analysis and, on the other, truncating review under the per se standard is a manifestation of the error cost framework.[44] In simple terms, truncated review costs less. When it is apparent to a court that challenged conduct is almost certainly anticompetitive, the risk of erroneously condemning that conduct under a truncated analysis is low, and the administrative cost savings comparatively high.

The dividing line between per se and rule of reason turns on information and probabilities: the extent to which the court has knowledge that the type of case presented is always or almost always harmful. Thus the Court has noted that the per se rule should be applied (1) “only after courts have had considerable experience with the type of restraint at issue” and (2) “only if courts can predict with confidence that [the restraint] would be invalidated in all or almost all instances under the rule of reason” because it “‘lack[s] . . . any redeeming virtue.’”[45]

Of course, precisely because certain knowledge about the competitive effects of most conduct is not available, condemnation under the per se standard is rarely appropriate. As a result, the error cost framework leads naturally to a preference for rule of reason analysis for most types of conduct.[46]

Although less often discussed,[47] but of no less importance, the error-cost framework also helps inform procedural as much as substantive liability rules. Many procedural rules serve as filters to eliminate the costly consideration of conduct that is unlikely to lead to consumer harm (costly both in terms of direct, administrative costs, as well as the risk of erroneous condemnation). Thus, antitrust procedure has a number of hurdles a plaintiff must overcome before a case is “proven.” Failure to overcome any of these hurdles could lead to a dismissal of the case, as early as a motion to dismiss before discovery.[48] Courts also dismiss cases at the summary judgment stage when there is no economic basis for the claims.[49] Similarly, antitrust assigns burdens of proof and adopts certain evidentiary presumptions within a burden-shifting framework, aimed at putting a thumb on the scale where economic knowledge warrants it.[50] The combination of procedural rules and burdens of proof helps to assure—in an environment of substantial uncertainty—that conduct harmful to consumers, and only such conduct, is condemned under a rule of reason analysis.

Antitrust injury and standing are among the first procedural hurdles a plaintiff faces.[51] Much like the per se standard, the doctrines of antitrust injury and standing serve as a filter meant to minimize the cost of adjudicating likely meritless claims. Importantly, in order to perform this function effectively, they must also reflect the underlying substantive knowledge of the conduct in question.[52]

Plaintiffs must also define the relevant market in which to assess the challenged conduct, including both product and geographic markets.[53] Particularly where novel conduct or novel markets are involved and thus the relevant economic relationships are poorly understood, market definition is crucial to determine “what the nature of [the relevant] products is, how they are priced and on what terms they are sold, what levers [a firm] can use to increase its profits, and what competitive constraints affect its ability to do so.”[54] In this way market definition not only helps to economize on administrative costs (by cabining the scope of inquiry), it also helps to improve the understanding of the conduct in question and its consequences.

Evidentiary burdens and standards of proof are particularly important implementations of the error cost framework. As noted, presumptions and burdens place an evidentiary “thumb on the scale” of antitrust adjudication, ideally in a manner reflecting underlying economic knowledge and its application to the specific facts at hand.[55] A plaintiff need not prove anticompetitive harm with certainty, or “beyond a shadow of doubt”: such a standard would, in most circumstances, not reflect the inherent uncertainty of conduct challenged under the antitrust laws. Under a “preponderance of the evidence” standard, by contrast, a plaintiff need adduce evidence sufficient only to demonstrate that challenged conduct is “more likely than not” to have anticompetitive effect. Plaintiffs in most civil litigation in the US, including antitrust litigation, are held to this standard.[56] Rebuttable presumptions are sometimes employed as a cost-saving substitute for direct evidence when economic theory predicts a relatively high probability of competitive harm.[57]

The choice of evidentiary standard—that is, the amount and kind of information supportive of the plaintiff’s claims she must produce, and the degree of certainty that evidence must engender in the court for it to decide in her favor—is crucial to the error-cost analysis which is, after all, a decision-theoretic device.

[A]ntitrust policy [is] a problem of drawing inferences from evidence and making enforcement decisions based on these inferences. . . . Using Bayes’ rule, we can write the policy maker’s belief about the relative odds that a given practice is anticompetitive as a function of his prior beliefs about the practice, and the relative likelihood that the evidence observed would be produced by anticompetitive conduct.[58]

But in an error-cost framework, it is by no means certain that a preponderance of the evidence—“more likely than not”—standard will generally minimize error costs. “[T]he decision theoretic approach. . . would not apply [the preponderance of the evidence] standard across the board. Instead, it would base decisions on expected error cost, not just the likelihood of prevailing.”[59] A preponderance of the evidence standard “would treat prospective errors in the direction of excessive enforcement as equally costly as prospective errors in the direction of lenient enforcement.”[60] Thus such a standard will optimize error costs only when the costs of Type I and Type II errors are the same.[61] But this will not always be the case.

While some have advocated reducing evidentiary burdens through presumptions of harm in certain situations,[62] Professors Mungan and Wright have persuasively argued that the preponderance of the evidence standard tends towards too many Type I errors, and should, in fact, be strengthened:[63]

The intuition behind this result is that while the optimal standard in other contexts is that which maximizes the deterrence of a single, bad conduct, the optimal standard of proof in antitrust must be set to both deter bad conduct and incentivize innovative and procompetitive conduct.[64]

In other words, in addition to uncertainty about what act is committed, there is uncertainty about the social desirability of each act which may have been committed. . . . [T]hese peculiar concerns in the field of antitrust law push the optimal standard of proof towards being stronger than in other contexts when Easterbrook’s priors hold, i.e. the beneficial impact of procompetitive behavior exceeds the impact of anticompetitive behavior. This finding suggests that courts which take Easterbrook’s priors as given can achieve the goals of antitrust not only by crafting substantive legal rules to impact behavior, but also by using standards of proof which are stronger than preponderance of the evidence.[65]

The Supreme Court has, in fact, adopted heightened evidentiary standards in some antitrust contexts. For instance, in Matsushita, after enunciating the summary judgment standard,[66] the Court went on to apply the error cost framework,[67] and came to the conclusion that coordinated predatory pricing was extremely unlikely under the facts presented.[68] In such situations, the Court required greater evidence to survive a motion for summary judgment.[69]

D. The Normative Error-Cost Framework: Why False Positives are More Concerning Than False Negatives

Crucial to Easterbrook’s conception of the error-cost framework are two normative premises: first, both Type I and Type II errors are inevitable in antitrust because distinguishing conduct with procompetitive effect from that with anticompetitive effect is an inherently uncertain and difficult task. Second, Type I errors are more costly than Type II errors, because self-correction mechanisms mitigate the latter far more readily than the former.[70] As a result, writes Easterbrook, “errors on the side of excusing questionable practices are preferable.”[71]

This version of the error-cost framework is not supported by all antitrust scholars, however, and there is a concerted effort today to condemn as unsupported, too permissive, and overly ideological the bias against enforcement that Easterbrook’s error-cost approach counsels.[72] As one recent account has it:

Given the Chicago assumption that markets tend to be self-correcting, type two errors—where the court fails to see anticompetitive conduct that actually exists—are not really problematic because the market itself will correct the situation. By contrast, false identification of harmful monopoly tends not to be self-correcting because a court blocks the efficient conduct for a long time. . . .

. . . If we reverse the premise and assume that markets tend more naturally to situations of market power, then the opposite presumption is warranted. Economic theory and evidence developed over the last forty years strongly support the reversed premise.[73]

There are several problems with this assessment, however.

1. The Weakness of the Evidence on Market Power and its Alleged Harms

First, it is surely correct that evidence to support Easterbrook’s presumption is not easy to come by—if it were there would be no need for the decision-theoretic approach in the first place. But the absence of evidence to support the claim is insufficient to condemn it: evidence to the contrary is just as unavailable. Indeed, as I discuss below, the unavailability of that knowledge is precisely one of the factors that supports the presumption.

According to Hovenkamp and Scott Morton, the “evidence developed over the last forty years [that] strongly support[s] the reversed premise” consists of the following:

The United States well overshot the mark in reducing antitrust enforcement after the late 1970s. Markups have risen steadily since the 1980s. The profit share of the economy has risen from 2% to 14% over the last three decades. The economic literature has come down solidly against the key early assumption of the Chicago thinkers that markets will self-correct. To the contrary, the evidence demonstrates that eliminating antitrust enforcement likely results in monopoly prices and monopoly levels of innovation in many markets.[74]

Beyond the studies cited by Hovenkamp and Scott Morton, there is a widely reported literature that has documented increasing national product market concentration.[75] That same literature has also promoted the arguments that increased concentration has had harmful effects, including increased markups and increased market power,[76] declining labor share,[77] and declining entry and dynamism.[78]

But there are good reasons to be skeptical of the national concentration and market power data. A number of papers simply do not find that the accepted story—built in significant part around the famous De Loecker and Eeckhout study[79]—regarding the vast size of markups and market power is accurate. Among other things, the claimed markups due to increased concentration are likely not nearly as substantial as commonly assumed.[80] Another study finds that profits have increased, but are still within their historical range.[81] And still another shows decreased wages in concentrated markets, but also that local concentration has been decreasing over the relevant time period.[82]

But even more important, the narrative that purports to find a causal relationship between these data and the various depredations mentioned above is almost certainly incorrect.

To begin with, the assumption that “too much” concentration is harmful assumes both that the structure of a market is what determines economic outcomes, and that anyone knows what the “right” amount of concentration is. But, as economists have understood since at least the 1970s (and despite an extremely vigorous, but ultimately futile, effort to show otherwise), market structure is not outcome determinative.[83]

Once perfect knowledge of technology and price is abandoned, [competitive intensity] may increase, decrease, or remain unchanged as the number of firms in the market is increased. . . . [I]t is presumptuous to conclude . . . that markets populated by fewer firms perform less well or offer competition that is less intense.[84]

This view is not an aberration, and it is held by scholars across the political spectrum. Indeed, Professor Scott Morton herself is coauthor of a recent paper surveying the industrial organization literature and finding that presumptions based on measures of concentration are unlikely to provide sound guidance for public policy:

In short, there is no well-defined “causal effect of concentration on price,” but rather a set of hypotheses that can explain observed correlations of the joint outcomes of price, measured markups, market share, and concentration. . . .

Our own view, based on the well-established mainstream wisdom in the field of industrial organization for several decades, is that regressions of market outcomes on measures of industry structure like the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index should be given little weight in policy debates.[85]

Furthermore, the national concentration statistics that are used to support these claims are generally derived from available data based on industry classifications and market definitions that have limited relevance to antitrust. As Froeb and Werden note:

[T]he data are apt to mask any actual changes in the concentration of markets, which can remain the same or decline despite increasing concentration for broad aggregations of economic activity. Reliable data on trends in market concentration are available for only a few sectors of the economy, and for several, market concentration has not increased despite substantial merger activity.[86]

Most importantly, however, this assumed relationship between concentration and economic outcomes is refuted by a host of recent empirical research studies.

The absence of a correlation between increased concentration and both anticompetitive causes and deleterious economic effects is demonstrated by a recent, influential empirical paper by Sharat Ganapati. Ganapati finds that the increase in industry concentration in non-manufacturing sectors in the US between 1972 and 2012 is “related to an offsetting and positive force—these oligopolies are likely due to technical innovation or scale economies. [The] data suggests that national oligopolies are strongly correlated with innovations in productivity.”[87] The result is that increased concentration results from a beneficial growth in firm size in productive industries that “expand[s] real output and hold[s] down prices, raising consumer welfare, while maintaining or reducing [these firms’] workforces.”[88]

A number of other recent papers looking at the data on concentration in detail and attempting to identify the likely cause for the observed data demonstrate clearly that measures of increased national concentration cannot justify a presumption that increased market power has caused economic harm. In fact, as these papers show, the reason for increased concentration in the US in recent years appears to be technological, not anticompetitive, and its effects seem to be beneficial.

In one recent paper,[89] the authors look at both the national and local concentration trends between 1990 and 2014 and find that: (1) overall and for all major sectors, concentration is increasing nationally but decreasing locally; (2) industries with diverging national/local trends are pervasive and account for a large share of employment and sales; (3) among diverging industries, the top firms have increased concentration nationally, but decreased it locally; and (4) among diverging industries, opening of a plant from a top firm is associated with a long-lasting decrease in local concentration.[90] The result, as the authors note, is that

the increase in market concentration observed at the national level over the last 25 years is being shaped by enterprises expanding into new local markets. This expansion into local markets is accompanied by a fall in local concentration as firms open establishments in new locations. These observations are suggestive of more, rather than less, competitive markets.[91]

A related paper shows that new technology has enabled large firms to scale production over a larger number of establishments across a wider geographic space.[92] As a result, these large, national firms have grown by increasing the number of local markets they serve, and in which they are actually relatively smaller players.[93] The net effect is a decrease in the power of top firms relative to the economy as a whole, as the largest firms specialize more, and are dominant in fewer industries.[94]

Economists have been studying the relationship between concentration and various potential indicia of anticompetitive effects—price, markup, profits, rate of return, etc.—for decades. There are, in fact, hundreds of empirical studies addressing this topic. Contrary to the claims of Hovenkamp and Scott Morton, however, taken as a whole this literature is singularly unhelpful in resolving our fundamental ignorance about the functional relationship between structure and performance: “Inter-industry research has taught us much about how markets look. . . even if it has not shown us exactly how markets work.”[95]

Nor do other suggested measures of supracompetitive returns—such as accounting measures of returns on invested capital—seem likely to offer any resolution. As one paper that advocates for the importance of such measures nevertheless makes clear, “[t]he welfare consequences of increasing sunk and fixed costs in an industry are complex, are probably industry specific, and may vary across antitrust and regulatory regimes. . . . It is difficult to see how cross-industry studies can capture the industry-level complexity that results from high fixed and sunk costs.”[96] Though some studies have plausibly shown that an increase in concentration in a particular case led to higher prices (although this is true in only a minority share of the relevant literature), assuming the same result from an increase in concentration in other industries or other contexts is simply not justified: “The most plausible competitive or efficiency theory of any particular industry’s structure and business practices is as likely to be idiosyncratic to that industry as the most plausible strategic theory with market power.”[97]

2. The Weakness of the Evidence of Under-Enforcement (Type II Errors)

But even assuming the trends showing increased concentration and/or markups are properly identified, it does not appear that the evidence connecting them to lax antitrust enforcement is very strong. Indeed, even proponents of this view express reservations about the state of the evidence.[98]

In their review of the state of antitrust law in 2004 Robert Crandall and Clifford Winston found “little empirical evidence that past interventions have provided much direct benefit to consumers or significantly deterred anticompetitive behavior.”[99] Theirs is not a condemnation of the overall level of enforcement, but a studied conclusion that the enforcement actions that were undertaken did not obviously further the goals of the antitrust laws.

As the FTC’s Michael Vita and David Osinski demonstrate in a thorough review of the critical literature, the claim of lax enforcement is fairly unconvincing on its own terms.[100] Although their study considered only merger enforcement, it is merger enforcement, of course, that is most relevant to claims of increasing concentration. Furthermore, the study’s results offer an important cautionary tale regarding the validity of claims of lax enforcement generally. Thus, Vita & Osinski’s thorough assessment of the evidence offered for the claim that “recent merger control has not been sufficiently aggressive”[101] finds, to the contrary, that:

[O]f the seven mergers in the 2000s [offered as evidence for the claim], four exhibited no increase in post-merger (or post-remedy) prices []; one had disputed results []; one represented a successful challenge to a consummated merger []; leaving only one (Whirlpool/ Maytag) indicative of potentially lax enforcement.[102]

Similarly, another recent study looking at FTC and DOJ merger enforcement data between 1979 and 2017 finds that:

[C]ontrary to the popular narrative, regulators have become more likely to challenge proposed mergers. . . . Indeed, controlling for the number of merger proposals submitted under HSR, the likelihood of a merger challenge has more than doubled over this period.[103]

The number of Sherman Act cases brought by the federal antitrust agencies, meanwhile, has been relatively stable in recent years, but several recent blockbuster cases have been brought by the agencies[104] and private litigants,[105] and there has been no shortage of federal and state investigations. But all of this is beside the point: for reasons discussed below, it is highly misleading to count the number of antitrust cases and, using that number alone, make conclusions about how effective antitrust law is.

The primary evidence adduced to support the claim that under-enforcement (and thus the risk of Type II errors) is more significant than over-enforcement (and thus the risk of Type I errors) is that there are not enough cases brought and won. But, even if superficially true, this is, on its own, just as consistent with a belief that the regime is functioning well as it is with a belief that it is functioning poorly. The antitrust laws have evolved over the course of a century, and in that time have developed a coherent body of doctrine to guide firms, courts, and enforcers.[106] It is entirely predictable that firms would, for the most part, be accurately guided in their affairs by the law and would largely avoid offending well-established competition principles:

For a given level of enforcement effort, the number of enforcement actions (and litigation generally) will be related to the extent of uncertainties and ambiguities about legal outcomes perceived by defendants. . . . If the number [of enforcement actions] is low, the reason could be lax enforcement or it could be clear legal standards and a reputation for vigorous enforcement. . . . Accordingly, in the absence of more information, counts of legal actions by themselves ought not to carry much weight.[107]

Further, in such a mature regime, one would expect relatively fewer marginal cases that present truly novel problems. Thus, the casual empiricism noting that 97 percent of Section 2 cases between February 1999 and May 2009 were dismissed based on the plaintiff’s failure to show anticompetitive effect[108] is not surprising, nor very telling. The vast majority of these cases—of which the study identifies 215 in all[109]—were brought by private plaintiffs pursuing treble damages. Such an outcome is as consistent with an antitrust litigation regime that decisively deters harmful conduct while overly encouraging plaintiffs to attempt to extract payouts as it is one that under-deters anticompetitive conduct.[110] A lack of cases and plaintiff’s victories cannot, on their own, justify an assertion that the antitrust regime is “lax.”

Moreover, assessing the economic consequences of our antitrust laws by considering the effects of only those enforcement actions actually undertaken is woefully misleading. As Douglas Melamed puts it:

Antitrust law [] has a widespread effect on business conduct throughout the economy. Its principal value is found, not in the big litigated cases, but in the multitude of anticompetitive actions that do not occur because they are deterred by the antitrust laws, and in the multitude of efficiency-enhancing actions that are not deterred by an overbroad or ambiguous antitrust law.[111]

For much the same reason, the purported evidence of under-enforcement inferred from the price effects of mergers found in merger retrospective studies[112] is unconvincing. Merger retrospectives are not a random sample of mergers from which the overall effect on conduct—including, crucially, conduct by parties deterred from merging as a result of enforcement actions against others—can be determined. Such evaluations are capable only of demonstrating the effects of potential Type II errors, and neither collect nor evaluate any evidence bearing on the incidence and cost of Type I errors.

3. The Strength of the Argument for Greater Concern with Type I Errors

As noted, some critics contend that the normative error-cost framework’s heightened concern for Type I errors stems from a faulty concern that “type two errors—where the court fails to see anticompetitive conduct that actually exists—are not really problematic because the market itself will correct the situation.”[113] But Easterbrook’s argument for enforcement restraint is not based on the assertion that markets are perfectly self-correcting. Rather, his claim is rooted in the notion that the incentives of new entrants to compete for supracompetitive profits in monopolized markets operate to limit the social costs of Type II errors more effectively than the legal system’s ability to correct or ameliorate the costs of Type I errors:

If the court errs by condemning a beneficial practice, the benefits may be lost for good. Any other firm that uses the condemned practice faces sanctions in the name of stare decisis, no matter the benefits. If the court errs by permitting a deleterious practice, though, the welfare loss decreases over time. Monopoly is self-destructive. Monopoly prices eventually attract entry. True, this long run may be a long time coming, with loss to society in the interim. The central purpose of antitrust is to speed up the arrival of the long run. But this should not obscure the point: judicial errors that tolerate baleful practices are self-correcting while erroneous condemnations are not.[114]

It is worth quoting him at length on this issue, as it has become central to the debate over the propriety of the error-cost framework:

One cannot have the savings of decision by rule without accepting the costs of mistakes. We accept these mistakes because almost all of the practices covered by per se rules are anticompetitive, and an approach favoring case-by-case adjudication (to prevent condemnation of beneficial practices subsumed by the categories) would permit too many deleterious practices to escape condemnation. The same arguments lead to the conclusion that the Rule of Reason should be replaced by more substantial guides for decision.

In which direction should these rules err? For a number of reasons, errors on the side of excusing questionable practices are preferable. First, because most forms of cooperation are beneficial, excusing a particular practice about which we are ill-informed is unlikely to be harmful. True, the world of economic theory is full of ‘existence theorems’—proofs that under certain conditions ordinarily-beneficial practices could have undesirable consequences. But we cannot live by existence theorems. The costs of searching for these undesirable examples are high. The costs of deterring beneficial conduct (a byproduct of any search for the undesirable examples) are high. When most examples of a category of conduct are competitive, the rules of litigation should be ‘stacked’ so that they do not ensnare many of these practices just to make sure that the few anticompetitive ones are caught. When most examples of a practice are procompetitive or neutral, the rules should have the same structure (although the opposite slant) as those that apply when almost all examples are anticompetitive.

Second, the economic system corrects monopoly more readily than it corrects judicial errors. There is no automatic way to expunge mistaken decisions of the Supreme Court. A practice once condemned is likely to stay condemned, no matter its benefits. A monopolistic practice wrongly excused will eventually yield to competition, though, as the monopolist’s higher prices attract rivalry.

Third, in many cases the costs of monopoly wrongly permitted are small, while the costs of competition wrongly condemned are large. A beneficial practice may reduce the costs of production for every unit of output; a monopolistic practice imposes loss only to the extent it leads to a reduction of output. Under common assumptions about the elasticities of supply and demand, even a small gain in productive efficiency may offset a substantial increase in price and the associated reduction in output. Other things equal, we should prefer the error of tolerating questionable conduct, which imposes losses over a part of the range of output, to the error of condemning beneficial conduct, which imposes losses over the whole range of output.[115]

While the Hovenkamp and Scott Morton criticism of the Easterbrook presumption rests on questioning just one of the underlying reasons Easterbrook gives for adopting it, Baker has undertaken a more thorough attempt at refutation.

Baker first claims that

[t]he unstated premise is that entry will generally prove capable of policing market power in the oligopoly settings of greatest concern in antitrust—or at least prove capable of policing market power with a sufficient frequency, to a sufficient extent, and with sufficient speed to make false positives systematically less costly than false negatives.

Yet there is little reason to believe that entry addresses the problem of market power so frequently, effectively, and quickly as to warrant dismissal of concerns regarding false negatives.[116]

These statements are largely unobjectionable. It has long been understood that the relevant comparison is between the costs of a monopoly erroneously allowed to persist for the time it takes to be mitigated by the market against the costs of erroneously deterring procompetitive behavior for as long as such a legal rule stands. “Markets do not purge themselves of all unfortunate conduct, and purgation (when it comes) is not quick or painless. . . . The point is not that business losses perfectly penalize business mistakes, but that they do so better than the next best alternative.”[117]

No scholars, including Easterbrook, actually “dismiss[] . . . concerns regarding false negatives”; rather, Easterbrook incorporates these concerns in his assessment by noting the relative time frames of market correction versus judicial correction and the relatively narrow consequences of allowing anticompetitive conduct versus the broad effects of deterring procompetitive conduct. These descriptive elements cannot be separated, and the assumption has never rested on a claim that Type II errors never happen, or that Type I errors are always virtually costless. Rather, as Easterbrook writes, “the economic system corrects monopoly more readily than it corrects judicial errors.”[118] He does not say that the economic system always and swiftly corrects monopoly.

The contrary assumption (in the pervasive absence of empirical evidence to support it[119]) is difficult to maintain. Even if only imperfectly or after a lengthy amount of time, it is a virtual certainty that anticompetitive conduct will be rectified or eventually rendered insignificant or irrelevant. But correction of legal error is far from certain and similarly (at best) distant in time. And there is little reason to be sanguine about the speed with which legal antitrust errors are rectified. It took nearly a century for the Leegin Court to correct the error of its per se rule against vertical resale price maintenance in Dr. Miles, for example[120]—even though the economics underlying Dr. Miles was called into question shortly after it was decided and firmly discredited by the economics profession 50 years later.[121] Yet it took another almost 50 years before the Court finally overturned its per se rule against RPM.[122]

Ironically, in fact, the extent to which an improperly stringent rule may subsequently be overturned is a function of its clarity. Within a plausible range,[123] the more certain and therefore more effective (and, therefore more stringent) the rule, the less likely firms would, whether intentionally or accidentally, run afoul of it. A rule that clearly prohibits all mergers over a certain size, for example, would likely be extremely effective, and few if any such mergers would be attempted. But this also means that there would be few opportunities to revisit the rule and potentially overturn it. Thus, an improperly harsh rule is more likely subsequently to be overturned the closer it is to the optimal rule—the less wrong it is, in other words. But for the same reason, overturning it would also be exactly that much less socially beneficial. Over the plausible range of overly-strict erroneous rules, the worst are less likely to be overturned, and the (relatively) best most likely to be reversed.

Moreover, anticompetitive conduct that is erroneously excused may be subsequently corrected, either by another enforcer, a private litigant, or another jurisdiction. An anticompetitive merger that is not stopped, for example, may be later unwound, or the eventual anticompetitive conduct that is enabled by the merger may be enjoined. Ongoing anticompetitive behavior (and, unfortunately, a fair amount of procompetitive behavior) will tend to arouse someone’s ire: competitors, potential competitors, customers, input suppliers. That means such behavior will be noticed and potentially brought to the attention of enforcers. For the same reason—identifiable harm (whether actually anticompetitive or not)—it may also be actionable. By contrast, procompetitive conduct that does not occur because it is prohibited or deterred by legal action has no constituency and no visible evidence on which to base a case for revision.

And, even if it did, there is no ready mechanism for revision anyway. A firm improperly deterred from procompetitive conduct has no standing to sue the government for erroneous antitrust enforcement, or the courts for adopting an improper standard. The existence of a judicial correction presupposes, at the very least, some firm engaging in conduct despite its illegality in the hope that its conduct will go unnoticed or the prior rule may be misapplied or overturned if it is sued. But the primary effect of a Type I error is the nonexistence of such conduct in the first place.

A related critique suggests that “Chicago School antitrust” (often used as a synonym for adherents to the error cost framework) is insensitive to an incumbent monopolist’s ability to deter entry, and thus to mitigate market correction. This critique asserts that the Chicago School approach rests on an indefensible “perfect competition” assumption:

Built into Chicago School doctrine was a strong presumption that markets work themselves pure without any assistance from government. By contrast, imperfect competition models gave more equal weight to competitive and noncompetitive explanations for economic behavior. . . .

. . . Because a firm has a financial incentive to use the profit from market power in order to maintain it, economic theory predicts that this would occur often. The Chicagoans thus needed an additional critical assumption: markets are inherently self-correcting and if left alone, they will work themselves pure.[124]

In other words, the reality that an incumbent monopolist may have the incentive and ability to act strategically to impede entry that could dilute its market power is claimed to be at odds with the Chicago School approach.[125]

Based on this, Hovenkamp and Scott Morton, for example, draw the tendentious conclusion that Chicago/error-cost antitrust scholars are disingenuous ideologues, actively suppressing economic science that contradicts their ideology:

When economic policy takes the model of perfect competition as its starting point, it has nowhere to go but downhill. If we did have a perfectly competitive economy, then of course antitrust intervention would be unnecessary. Faced with the choice of moving to models that provided greater verisimilitude and predictability, but that required more intervention, or clinging to the past, the Chicago School chose the latter.[126]

But this is, at best, a willfully misleading caricature of the Chicago School. Indeed, it is arguably more accurate to say that the pervasiveness of the misallocation of property rights and the presence of transaction costs in the market is not only appreciated by the Chicago School, but it forms a core part of its adherence to Easterbrook’s claim that Type I errors are more problematic than Type II errors.[127]

To begin, the assumption of perfect competition is not, in fact, a part of the Chicago School enterprise. Indeed, it was Chicago School scholars[128] who introduced the analyses that undermined the assumptions of perfect competition that prevailed during the inhospitality era. Thus, for example, scholars like Ronald Coase and Oliver Williamson introduced the fundamental notion that unfettered market allocation was frequently inefficient and that private ordering—ranging from nonstandard contracts to firms themselves—was primarily aimed at ameliorating the inefficiencies of atomistic markets.[129] Scholars like Lester Telser, Ward Bowman, and Howard Marvel explained why assumptions of perfect information were inappropriate.[130] Chicago scholars like Ben Klein and Armen Alchian developed the notion that the risk of appropriation of assets over time could undermine efficient investment against the perfect competition model that assumed no time inconsistency.[131] Meanwhile, Chicago scholars, who first introduced the “single monopoly profit” theory explaining why much conduct, like tying, should not be per se illegal, also anticipated and understood the limitations of the theory.[132] Similarly, Chicago scholars anticipated the raising rivals’ cost (“RRC”) literature[133] and were the first to note its theoretical possibility as an explanation for deviation from the model of perfect competition.[134] They also offered the most comprehensive empirical evidence of its existence.[135]

As Professor Meese summarizes, it was Chicago School (and “fellow traveler”) scholars who stepped in to correct inappropriate reliance on perfect competition models; they did not advocate it:

[Pre-Chicago School] scholars considering questions of market failure did so on the assumption that markets were perfectly competitive. This assumption was not a statement about the actual state of the world, but instead a component of a theoretical model designed to guide scientific research. This methodological habit prevented these scholars from recognizing that various non-standard contracts could overcome market failure. In the absence of a beneficial explanation for these agreements, scholars naturally treated these departures from perfect competition as manifestations of market power.[136]

There is a long and unfortunate history of antitrust institutions (including courts and enforcers) erroneously condemning nonstandard business practices as problematic deviations from a theoretical model of perfect competition.[137] The urge to condemn practices not fully understood arises from an implicit (or sometimes explicit) assumption that deviations from perfect model assumptions are more likely than not expressions of market power, rather than corrections of underlying market failures. As Ronald Coase described this phenomenon decades ago:

If an economist finds something . . . that he does not understand, he looks for a monopoly explanation. And as in this field we are rather ignorant, the number of ununderstandable practices tends to be rather large, and the reliance on monopoly explanations frequent.[138]

Modern economics and antitrust further persist in this inhospitality tradition by, for example, dismissing business strategy and other “soft” literatures[139] that identify and explain reasons for market-correcting structures assumed by much of modern economics to be anticompetitive deviations.[140] The continued adherence to perfect competition assumptions by critics of the Chicago School is what induces them to assume that Type I errors are less problematic. Combined with an unsupported (and often implicit) assumption of heightened government ability, this also leads to the unsupported assumption that Type II errors are less problematic.[141] As Meese puts it:

Reliance on the perfect competition model, I submit, accounts for the failure of modern scholars to offer any account of the formation and enforcement of non-standard contracts that does not depend on the possession or exercise of market power. By focusing solely on the propensity of non-standard contracts to reduce ‘transaction costs,’ these scholars ignore the fact that such agreements also reverse market failures by internalizing externalities and thus altering the costs faced by parties to such agreements. Thus, such restraints naturally produce prices or output different from what would obtain in an unbridled market.[142]

The modern approach makes these assumptions even without recognizing it, for instance by relegating consideration of merger efficiencies to a separate analysis from the analysis of competitive effects, on the assumption that efficiencies can manifest only in the form of relative increases in output—not that the efficiency gained may be the elimination of competition and conceivably the reduction in output in the first place. “Within this framework, efficiencies necessarily manifest themselves as lower production costs and thus increased output of the product than existed before the restraint. This merger paradigm is ill-suited for evaluation of restraints that purportedly overcome market failure.”[143]

In this conception, any reduction in the number of competitors or constraint on the freedom of market participants is a threat to competition—essentially a movement away from the perfect competition ideal. It does not readily admit of reallocation of resources according to better knowledge and coordination as an inherent benefit, unless it manifests in the form of reduced production costs and increased output.[144] In this sense both Chicago and non-Chicago scholars rest substantially on partial equilibrium analysis and a perfect competition baseline, in contrast to evolutionary,[145] dynamic capabilities,[146] resource-advantage,[147] and similar[148] approaches that do actually eschew the baseline of perfect competition. None of these approaches has had significant influence on the development of antitrust policy and law, however. “For over thirty years, the economics profession has produced numerous models of rational predation. Despite these models and some case evidence consistent with episodes of predation, little of this Post-Chicago School learning has been incorporated into antitrust law.”[149]

By stark contrast, the practical, legal status of Easterbrook’s claim is today well-enshrined in antitrust law.

[Thirty-six] years after Judge Easterbrook’s seminal article, the Supreme Court has effectively written Easterbrook’s principal conclusion about error costs into antitrust jurisprudence. Less ideological campaign, more convergent evolution, this process has spanned decades, over a series of opinions, and includes the votes of at least 14 different Justices. Time and again, when confronted with deep questions in antitrust law, those Justices, have reached the same conclusion: False positives are more harmful than false negatives in antitrust.[150]

A number of cases establish this, including several seminal Supreme Court and appellate antitrust decisions.[151]

Nor is it likely that the courts are making an erroneous calculation in the abstract. Evidence of Type I errors is hard to come by, but, for a wide swath of conduct called into question by “Post-Chicago School” and other theories, the evidence of systematic problems is virtually nonexistent.[152] This state of affairs may make it appropriate to adjust the implementation of the error-cost framework in any specific case as the relevant evidence suggests, but it does not counsel its abandonment. “Given the state of empirical knowledge, broad policy questions necessarily rely upon imprecisely estimated factors. As a result, a wide range of policy approaches based on the same error cost methodology is possible.”[153]

Thus, for example, for the conduct most relevant to digital markets—vertical restraints—the theoretical literature suggests that firms can engage in anticompetitive vertical conduct, but the empirical evidence suggests that, even though firms do impose vertical restraints, it is exceedingly rare that they have net anticompetitive effects. Nor is the relative absence of such evidence for lack of looking: countless empirical papers have investigated the competitive effects of vertical integration and vertical contractual arrangements and found predominantly procompetitive benefits or, at worst, neutral effects.[154]

To be sure, there are empirical studies showing that vertically integrated firms follow their unilateral pricing incentives, which means that they do increase prices charged to firms that compete downstream, resulting in increased consumer prices. But it also means that they eliminate double marginalization, resulting in lower consumer prices. Several recent papers have found both effects—and found both that the effects are small and almost exactly offsetting. As one of these papers concludes:

Overall, we find that both double-marginalization and a supplier’s incentive to raise rival’s costs have real impacts on consumer prices. However, these effects in the gasoline markets we study are small. Both the double marginalization effect and raising rival’s cost effect are roughly 1 to 2 [cents per gallon], or roughly 0.76%-1.5% of the price of gasoline. The net effect of vertical separation on retail gasoline prices was essentially zero. . . .[155]

The same is true for other forms of conduct relevant to digital markets. The primary, mainstream theoretical challenge to the normative error-cost framework (and to Chicago School antitrust more generally) is found in the RRC literature.[156] RRC offers a theoretically rigorous, alternative, anticompetitive theory for much ambiguous conduct, including conduct identified by early Chicago School scholars as having plausible procompetitive bases (and often recognized by the courts through the removal of per se illegality).

But, while the identification of a compelling theory of harm for such conduct may alter the specific contours of a decision-theoretic assessment under the Rule of Reason, it does not fundamentally alter the recognition that per se illegality is inappropriate, nor even that any specific doctrinal process element of the Rule of Reason is improperly imposed.[157] Because all of these are implemented in fundamentally discretionary fashion, a court need not, say, reverse the burden of production in order to implement the status quo burden-shifting framework in a way that demands relatively more of one side or the other based on the court’s understanding of the relative applicability of anticompetitive RRC theories and procompetitive Chicago School theories.

Thus it is crucial to note that, despite claims by Chicago School critics that RRC and other developments in economic theory (most notably game theory[158]) should undermine the normative error-cost approach and lead courts to different outcomes, there is not, in fact, a sound evidentiary basis on which to rest this assertion. Judged on the very criteria by which Chicago School critics maintain the superiority of Post-Chicago theories, in fact, these models distinctly fail to “provide[] greater verisimilitude and predictability.”[159] Indeed, they may even reduce our ability to make reliable predictions on which to base policy: “While additional theoretical sophistication and complexity is useful, reliance on untested and in some cases untestable models can create indeterminacy, which can retard rather than advance knowledge.”[160] As Kobayashi and Muris emphasize, the introduction of new possibility theorems, particularly uncorroborated by rigorous empirical reinforcement, does not necessarily alter the implementation of the error-cost analysis:

While the Post-Chicago School literature on predatory pricing may suggest that rational predatory pricing is theoretically possible, such theories do not show that predatory pricing is a more compelling explanation than the alternative hypothesis of competition on the merits. Because of this literature’s focus on theoretical possibility theorems, little evidence exists regarding the empirical relevance of these theories. Absent specific evidence regarding the plausibility of these theories, the courts . . . properly ignore such theories.[161]

RRC is no more amenable to concrete implementation by courts: “As with almost all monopolization strategies, one cannot distinguish an anticompetitive use of RRC from competition on the merits, absent a detailed factual inquiry. . . . [T] here is very little empirical evidence based on in-depth industry studies that RRC is a significant antitrust problem.”[162]

II. Error Costs in Digital Markets: The Problem of Innovation

The arguments in favor of the normative error-cost framework are even stronger in the context of the digital economy. The concern with error costs is especially high in dynamic markets in which it is difficult to discern the real competitive effects of a firm’s conduct from observation alone. And for several reasons, antitrust decision-making in the context of innovation tends much more readily toward distrust of novel behavior, thus exacerbating the risk and cost of over-enforcement.

As noted, there is an “uneven history of courts and enforcement officials in enhancing welfare through antitrust,” suggesting reason to be skeptical.[163] In the face of innovative business conduct, the concern is compounded by the problematic incentives of antitrust economists. As Manne and Wright note:

Innovation creates a special opportunity for antitrust error in two important ways. The first is that innovation by definition generally involves new business practices or products. Novel business practices or innovative products have historically not been treated kindly by antitrust authorities. From an error-cost perspective, the fundamental problem is that economists have had a longstanding tendency to ascribe anticompetitive explanations to new forms of conduct that are not well understood.[164]

The two problems are related. Novel practices generally result in monopoly explanations from the economics profession, followed by hostility from the courts. Often a subsequent, more-nuanced economic understanding of the business practice emerges, recognizing its procompetitive virtues, but this also may come too late to influence courts and enforcers in any reasonable amount of time—and it may never tip the balance sufficiently to appreciably alter established case law. Where economists’ career incentives skew in favor of generating models that demonstrate inefficiencies and debunk the Chicago School status quo, this dynamic is not unexpected.

At the same time, however, defendants engaged in innovative business practices that have evolved over time through trial and error regularly have a difficult time articulating a justification that fits either an economist’s limited model or a court’s expectations. Easterbrook ably described the problem:

[E]ntrepreneurs often flounder from one practice to another trying to find one that works. When they do, they may not know why it works, whether because of efficiency or exclusion. They know only that it works. If they know why it works, they may be unable to articulate the reason to their lawyers-because they are not skilled in the legal and economic jargon in which such “business justifications” must be presented in court. . . .

. . . It takes economists years, sometimes decades, to understand why certain business practices work, to determine whether they work because of increased efficiency or exclusion. To award victory to the plaintiff because the defendant has failed to justify the conduct properly is to turn ignorance, of which we have regrettably much, into prohibition. That is a hard transmutation to justify.[165]

Imposing a burden of proof on entrepreneurs—often to prove a negative in the face of enforcers’ pessimistic assumptions—when that burden can’t plausibly be met can serve only to impede innovation.[166]

Even economists know very little about the optimal conditions for innovation. As Herbert Simon noted in 1959,

Innovation, techcological change, and economic development are examples of areas to which a good empirically tested theory of the processes of human adaptation and problem solving could make a major contribution. For instance, we know very little at present about how the rate of innovation depends on the amounts of resources allocated to various kinds of research and development activity. Nor do we understand very well the nature of “know how,” the costs of transferring technology from one firm or economy to another, or the effects of various kinds and amounts of education upon national product. These are difficult questions to answer from aggregative data and gross observation, with the result that our views have been formed more by arm-chair theorizing than by testing hypotheses with solid facts.[167]

Our understanding has not progressed very far since 1959, at least not insofar as it is applied to antitrust.[168] Simon astutely infers that innovation would be a function of “human adaptation and problem solving”; “the amounts of resources allocated to various kinds of research and development activity”; the nature of ‘know how’”; “the costs of transferring technology”; and “the effects of various kinds and amounts of education.” But economists today tend to focus primarily on how market structure affects innovation. As Teece notes, however:

A less important context for innovation, although one which has received an inordinate amount of attention by economists over the years, is market structure, particularly the degree of market concentration. Indeed, it is not uncommon to find debate about innovation policy among economists collapsing into a rather narrow discussion of the relative virtues of competition and monopoly. . . .

. . . [Yet] reviews of the extensive literature on innovation and market structure generally find that the relationship is weak or holds only when controlling for particular circumstances. The emerging consensus is that market concentration and innovation activity most probably either coevolve or are simultaneously determined.[169]

Even to the extent that economic science has developed some better theories of innovation and its relationship with market structure and antitrust, the literature has still failed to develop clear and concrete theories or empirics that are readily implementable by courts or enforcers in the face of complex economic conditions.[170] Particularly to the extent that contemporary monopolization theorems purport to address novel, often-innovative business practices, they are problematic for antitrust law and policy aiming to maximize welfare (minimize errors), for several reasons.

First, they engender circumstances that increase the likelihood of antitrust complaints, investigations, and enforcement actions.[171] In the face of limited evidence, untestable implications, and possibility theorems regarding the consequences of novel, innovative conduct, a proper application of error-cost principles would likely be expected to deter intervention. Yet it is precisely in these situations that intervention may be more likely.

On the one hand, this may be because in the absence of information disproving a presumption of anticompetitive effect, there is an easier case to be made against the conduct—this despite putative burden-shifting rules that would place the onus on the complainant. On the other hand, successful innovations are also more likely to arouse the ire of competitors and/or customers, and thus both their existence and their negative characterization are more likely brought to the attention of courts or enforcers—abetted in private litigation by the lure of treble damages.

Antitrust is skeptical of, and triggered by, various changes in status quo conduct and relationships. This applies not only to economists (as discussed above),[172] but also to competitors (who are likely to raise challenges to innovative, even if perfectly procompetitive, conduct that makes competition harder), enforcers (who are inherently on the look-out for cutting-edge cases because clearly infringing conduct is rare and opportunities to expand their authority attractive), and judges (who may be particularly swayed by economists’ possibility theorems to believe that they can make upholdable new law).

Business process and organizational innovations are also more relevant to the sorts of conduct with which antitrust concerns itself. New technological advance is rarely an inherent problem for antitrust; rather, its presence increases the potential cost of over-deterrence, but not necessarily its likelihood.[173] But novel technologies are frequently accompanied by novel business arrangements—and these are of particular concern to antitrust.