Introduction

Politicians, academics, pundits, journalists, and others have raised many concerns about large technology companies and offered a variety of solutions. Currently, these companies are regulated under general consumer and antitrust law and sector-specific laws that apply to their many different business models. Many have called for changes to these laws to address their concerns. Some go further, proposing not just new regulation, but an entirely new regulator. They seek a new federal agency, a “digital regulator,” to address a wide range of issues involving some of the largest companies in the world.

Policymakers must weigh the benefits and costs of creating an entirely new digital regulator. The choice of implementing regulator can make or break a regulation, almost regardless of its substance. If policymakers understand the tradeoffs, they can better ensure that any new regulation will be set up for success over the long term.

In this chapter we explain that creating a new agency has potential benefits and risks. The typical anticipated benefit of creating a new agency is specialized expertise. An expert agency holds a comparative advantage over general regulators or legislators that justifies its existence. Those who propose a new agency must, therefore, identify what unique, necessary, but unavailable expertise justifies the creation of the new agency.

The principle risk of creating a new sector-specific agency is regulatory capture. An agency that primarily serves industry’s interest can leave the public worse off than no agency at all. This is particularly true in rapidly innovating sectors, where incumbents have a strong incentive to use government to prevent disruptive innovation by potential competitors. Those who propose a new agency must acknowledge and at least attempt to mitigate this risk.

Have digital regulator advocates demonstrated that its specialized expertise will generate benefits that outweigh the threat of regulatory capture favoring incumbents? This chapter examines four different representative regulatory proposals to answer that question.

Earlier sections of this report provide the background to this examination. Section I talks at length about the characteristics of digital platforms, network effects, the relevant economics of IP, and legal issues such as vertical integration, vertical restraints, and self-preferencing. Section II looks at alleged problems with the status quo, examine impacts on concentration, innovation, consumer surplus, labor economics, rent seeking, and what antitrust regulators are doing in the EU and the US about these problems.

We now turn to Section III. This section examines proposed solutions to the alleged flaws. The following chapters will look at many dimensions of proposed reforms. But this chapter will focus on one: whether a new regulatory agency is necessary. Along the way, informed by the thinking in Section I, we will touch on whether there is something unique about “tech companies” that necessitates a new expert regulator. Similarly, drawing on the lessons from Section II, we will examine the alleged gaps in how current regulators govern tech companies to understand what comparative advantages a new agency might have.

We conclude that existing proposals have failed to demonstrate that a new agency’s expected benefits outweigh its likely risks. The proposals do not identify what area of expertise would give the digital regulator a comparative advantage over existing agencies. Nor do they discuss or mitigate a digital regulator’s heightened risk of capture.

In short, judging by these proposals, big tech does not need its own regulator.

I. The Representative Proposals

Calls for increased regulation of large tech companies have exploded over the past several years.[1] Many of those calls have contemplated creating a new watchdog agency focused on tech companies.[2] But most proposals have been light on details. Only a few have sought to justify such an agency or explain what it would do or how it would work. Below we summarize the four most prominent proposals for a new digital regulator.

A. UK Competition and Markets Authority’s Digital Markets Unit

In July of this year, the United Kingdom’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), a government agency focused on competition issues, issued a report proposing a new agency to regulate digital companies.[3] The CMA proposes that this agency, the “Digital Markets Unit,” (DMU) possess broad authority over major “online platforms funded by digital advertising,” specifically including Google and Facebook.[4] The report recommends that the DMU have authority allowing it to mandate that firms share search data with rivals, require interoperability features between platforms, and create an obligation for platforms to include designs that maximize consumer choice over their privacy and data collection. It emphasizes that large digital platforms maintain such powerful market positions that new entrants cannot compete without some form of government intervention.

The report has “not considered which institutions might be best placed to discharge those functions.”[5] As such, it “use[s] the term DMU very broadly, noting that this could be a new or an existing institution, or even that the functions could be assigned across several bodies.”[6] In short, the CMA report is indifferent to whether the DMU is a separate new agency or not.

B. Stigler Committee on Digital Platforms’ Digital Authority

The Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State issued a report in 2019 proposing that Congress create a Digital Authority to better address competition and consumer privacy issues in the digital economy.[7] The authors argue that the digital economy presents unique challenges, such as network effects enabling platforms to attract large user bases and gather user data, that current regulatory agencies cannot address. Thus, the report proposes a Digital Authority with the primary goal of establishing competition in digital markets. According to the report, an effective Digital Authority would be able to collect data from digital firms, especially large firms, to monitor their practices; enforce interoperability rules between platforms; and promote standardized features across firms. The authors also suggest that a Digital Authority should possess the ability to scrutinize mergers and acquisitions of any size that involve a platform with “bottleneck” capabilities and to enforce a variety of remedies in cases where firms engage in anti-competitive conduct.

As to where new regulatory authority should reside, the Stigler report gives conflicting answers. The body of the report repeatedly calls for a “a specialist regulator, the Digital Authority,” a “sectoral regulator,” and “a new digital regulatory agency.”[8] Yet the Policy Brief for Regulators, which introduces the report, states, “[W]e envision—at least initially—to have the Digital Authority as a subdivision of the FTC, an across-industry authority with a better-than-average record of avoiding capture.”[9] That is, motivated by regulatory capture concerns, the Policy Brief recommends against creating a stand-alone agency.

It is not clear what institutional form the Stigler Center ultimately supports. The above sentence in the Policy Brief is the only place in the entire report where the Center recommends against a new agency. But after the release of the report, two of the leading contributors elaborated on a FTC subdivision in a subsequent blog post, detailing how “[r]otating FTC staff between consumer protection, antitrust, and digital authority could create useful synergies and expertise and minimize the risk that DA employees will be captured by industry.”[10] By continuing to discuss the potential various arrangements at the FTC, the authors suggest that the Stigler Center would support enhancing FTC authority rather than creating a new agency—at least for now.

C. Harold Feld – The Case for the Digital Platform Act

In his report, “The Case for the Digital Platform Act,” Harold Feld, senior vice president at progressive tech policy think tank Public Knowledge, argues that the complexities of the digital industry require a specialized regulatory agency. Feld claims that digital platforms wield significant influence in society, create new consumer protection challenges, and affect critical social values including free expression and democratic participation. He states that technology companies that offer multiple services can utilize network effects to rapidly grow and expand their user base with low marginal costs.[11] Feld also notes that users endure particularly high costs when excluded from platform services and that they often enhance a platform’s network effects by performing several roles as consumers.[12] He emphasizes that a digital regulatory agency should possess the power to limit a firm’s market power by limiting mergers, if the agency determines that the firm’s size negatively impacts the public interest. Feld also notes that the agency should design a variety of merger remedies for dominant firms and design new remedies for a multitude of problems associated with the digital industry, such as device addiction.

Feld proposes that Congress either grant an existing agency (he favors the Federal Communications Commission) with new authority or create a new agency that can address the unique capabilities of internet companies and prevent anticompetitive conduct in the digital sector.[13] Under either regulatory scenario, Feld argues that the responsible agency would need to possess a “comprehensive set of regulatory mechanisms” and wide-ranging authority befitting a public-utility regulator to protect consumers, increase competition, and ensure that all members of the public can access reliable service.[14]

D. Shorenstein Center’s Digital Platform Agency

Three Senior Fellows at Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center—former FCC chairman Tom Wheeler, former FCC Senior Counsellor to the Chairman Phil Verveer, and public interest lawyer and former DOJ antitrust staffer Gene Kimmelman—have just issued a discussion paper with a blueprint for a Digital Platform Agency (DPA).[15] Compared to the other proposals, the Shorenstein report lays out a detailed structure and obligations for a DPA.

The Shorenstein report argues that the internet of today is unregulated and has not served the public interest. Current agencies are unsatisfactory, it claims, because they lack “digital DNA,”—meaning technical expertise and market expectations appropriate for digital technologies. And current agencies are also already overburdened.

A new bi-partisan independent DPA would “fill the void” left by outdated legislation. Its jurisdiction would be “consumer-facing digital activities of companies with significant strategic market status.”[16] Small companies would not be targeted.

The report recommends that the DPA discard the “industrial era” approach to regulation and instead adopt a new, agile, risk-management approach to governance. The foundations of this approach are inspired by two common law ideas: the duty of care and the duty to deal. (To be crystal clear, the DPA would not be bound by common law or pursue such actions in common law courts but would deploy its regulatory tools in the spirit of these two duties.) A Code Council “of industry and public representatives possessing demonstrated expertise” would develop codes of conduct which could be adopted and enforced by the DPA.

Unlike the proposals we have discussed thus far, the Shorenstein Center report is unequivocal that a new agency is needed. We should “not bolt on authority to an existing agency,” the report argues, because “[e]xisting agencies, as a result of their statute, staff, tradition and jurisprudence are infused with an inherently analog DNA” when what is needed is “digital DNA.”[17] “Old agencies (even if their statutes are updated) are saddled with legacy precedents . . . ,” it claims.[18] Existing agencies are also stretched thin executing their current duties. Therefore, “[r]ather than bolt on to and dilute an existing agency’s responsibilities, it is preferable to start with a clean regulatory slate and specifically established congressional expectations.”[19]

E. Other Proposals

The four proposals summarized above are not the only proposals to create a new agency, but they are the key proposals for regulatory agencies that focus on competition issues.

Others have proposed non-competition related agencies. For example, some legislators have proposed creating a new privacy agency that would affect tech companies—and other companies as well. Democratic congresswomen Zoe Lofgren and Anna Eshoo introduced the Online Privacy Act, and Senator Kirsten Gillibrand introduced the Data Protection Act of 2020. Both proposals would create an independent agency dedicated to enforcing commercial privacy rights for consumers. In another example, a proposal from Paul Barrett at New York University’s Stern Center for Business and Human Rights calls for an “independent digital oversight authority” as part of a response to the debates over social media content moderation.[20]

Economist Hal Singer has proposed a “net tribunal” to adjudicate complaints against technology companies (and potentially others) for exclusionary conduct and harm to innovation through various self-preferencing practices.[21] He argues that current antitrust law cannot address these practices, and even if it can, it moves too slowly to prevent innovation harms.[22] Like Feld, Singer looks to the FCC to provide a template for his proposal, basing the tribunal on the program carriage proceedings established by Congress in the 1992 Cable Act. Unlike the other proposals, Singer’s net tribunal is not a sector-specific agency. Indeed, he envisions a tribunal that would apply a nondiscrimination standard across all layers of the internet and potentially beyond.[23] In fact, the net tribunal is more a court than an agency. As such, while Singer states that the net tribunal could be housed either in a new agency or as a new division within the FTC, this type of topically narrow but economy-wide adjudicative body seems best suited to be incorporated within the FTC, which already has structurally similar capabilities.[24]

The below discussion is often responsive to these various other proposals, but because they do not focus on competition or do not propose a sector-specific agency, we do not expressly address their arguments.

* * *

One summary note before continuing: on the key question of this chapter—does big tech need its own regulator—three of the four major proposals equivocate. Feld seems to prefer an independent regulator but would be satisfied with new authority at the FCC.[25] The body of the Stigler Center report repeatedly recommends a new agency, but the Policy Brief backs off that recommendation, proposing instead that the authority be granted to the FTC, at least initially.[26] And the CMA report expressly states that it has not considered the question and appears open to a range of institutional forms.[27] Only the Shorenstein Center report decisively recommends against “bolt[ing] on authority to an existing agency.”[28]

So, if we take these proposals at their word, their answer to “Does big tech need its own regulator?” would appear to be, “Maybe not.”

Still, creating a new agency remains on the menu of options that future regulators and legislators will be ordering from. Is it a good option?

II. Agencies Must Be Expert in Something

Before we evaluate the various proposals to create a new regulator for big tech, it is worth revisiting a foundational question: why create agencies at all? Government is often asked to, and often attempts to, solve problems. But what justifies Congress tasking an agency with solving these problems, rather than doing so itself?

A. The Traditional Rationale: Division of Labor by Expertise

The generally accepted reason for creating agencies is division of labor by expertise—in a word, specialization. Yale law professor Jonathan R. Macey describes “the old justification for administrative agencies as a dominant fixture of American law: unlike courts or legislatures, administrative agencies are staffed by ‘experts’ whose knowledge of the circumstances and conditions within a particular industry enables them to execute their duties in a professional manner.”[29] In other words, administrative agencies are experts—they know something about an issue that others do not. That knowledge gives the agency an advantage over other institutions when dealing with that issue. Compared to a general legislative body, an institution with expertise in a specific set of problems can more efficiently and effectively apply governmental powers to that set of problems.

Thus, an agency’s expertise justifies its existence.

To justify a new agency, then, one must identify an unsatisfied need for unique expertise. Delegating problems to an agency creates no comparative advantage if the knowledge needed to solve the problem is commonplace or easily accessible. No expert agency is needed in that case. Likewise, delegating unrelated problems that require different expertise to the same agency creates no efficiencies. If another agency already possesses relevant expertise, it makes more sense to assign the problems to that agency.

B. Different Kinds of Agency Expertise

But not all expertise is the same. Distinguishing between different types of expertise that an agency might acquire will help us analyze the proposals’ calls for a new expert agency.

One can divide agency-relevant expertise into three crude categories: industry, policy, and procedure. All agencies have each kind of expertise, but most agencies are organized around either industry or policy expertise.

First, regulators have industry expertise in the technical, economic, and business model characteristics of the companies they regulate. For example, the Federal Aviation Administration sets requirements for airplane design and operation, and thus requires expertise in aircraft design, air traffic control, and aviation safety. Industry expertise differs greatly in its substance between industries. And for fast-changing industries, such expertise can quickly become outdated.

Most U.S. agencies are organized around industry expertise. This includes sector-specific agencies like the Federal Communications Commission or the Federal Aviation Administration or many others covering other specific sectors such as healthcare, automotive transportation, and finance. Such regulators are responsible for addressing a wide range of different kinds of problems throughout a single sector. Their knowledge of a specific industry provides a comparative advantage in handling problems that arise in that industry.

The depth of industry expertise an agency can develop given a set amount of resources will depend in part on how broadly or narrowly the industry is defined. An agency charged with governing a narrowly defined industry can develop deeply specialized knowledge compared to an agency with broader jurisdiction. But too narrow a definition can be inefficient. It would likely be inefficient to have one FAA for airplanes and a different FAA for helicopters, for example.

Second, regulators also have policy expertise in recognizing and addressing the specific problems or harms at issue. Policy expertise includes understanding and applying the general principles and rationales for government intervention, such as a basic understanding of market failures. It also includes knowledge about problems that span many industries. For example, the Federal Trade Commission has legal and economic expertise in analyzing anticompetitive behaviors, which can occur in many industries.

General regulators like the Federal Trade Commission, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Consumer Product Safety Commission are organized around policy expertise. Their core organizing principle is the policy problem or problems they are tasked with solving, not any specific industry. Such problems involve a shared set of legal requirements and economic principles that are applicable across many industries.

A third category of expertise might be called procedural expertise. This encompasses the legal and practical knowledge of regulatory process—the business of being an administrative agency. This can differ from agency to agency. For example, the FCC has deep experience in administrative rulemaking, while the FTC has deep experience in enforcement and litigation.

C. Implications of the Three Types of Expertise for Agency Specialization

Agencies will differ structurally based on which types of expertise they emphasize. Policy and procedural expertise apply in nearly every regulatory situation and are therefore more widely available than industry expertise. Industry expertise is, by its nature, specific to a single industry. In contrast, agencies are governed by overarching procedural requirements such as the Administrative Procedure Act. Each agency has its own internal rules, but all build from a common foundation of procedural expertise. And policy expertise exists at some level in every agency. For example, every agency requires expertise in the types of market failure that justify regulatory interventions. Similarly, the types of harms from which government seeks to protect consumers are necessarily more general than the types of business models or industries that might cause that type of harm. In both cases this would lead one to expect that policy expertise in recognizing and dealing with market failure and consumer harm likely resides in many different agencies. And in fact, that is the case.[30]

As mentioned, all agencies have each type of expertise, just with different emphasis. The Federal Communications Commission, for example, has deep industry expertise in the wireless telecommunications industry. But it also has procedural expertise in rulemaking, an expertise with application far beyond the communications industry. And the Federal Trade Commission, although a generalist regulator, has built expertise in a range of industries over time as it repeatedly applies its authority to those industries. Such industry expertise is acquired (permanently or on contract) as necessary to address a specific competition or consumer protection problem.[31]

Put briefly, an agency’s mission can focus either on addressing many different problems in the same industry or focus on addressing the same type of problem across many different industries.

Thus, deciding whether a new agency is appropriate hinges on answering “yes” to two questions. First, is it possible to identify a differentiated industry or sector for the new expert agency? If not, a new, sector-specific agency would likely duplicate expertise already at other agencies. Second, would a new agency have a comparative advantage over an enhanced existing agency? Answer yes to both questions, and creating a new agency may have benefits—although those benefits may come with significant costs, as we will see in Section IV.

III. A New Agency Expert in What?

Tested against these two questions, the proposals do not make a strong case for a new agency because they cannot explain what expertise the new agency will develop. They struggle to define the very sector to be regulated. Most of them do not argue that a new agency would have a comparative advantage over existing agencies. Two proposals do, however. One shows only that a new agency may have a slight comparative advantage in procedural expertise. The other makes a few arguments in favor of a new agency, but ultimately throws up its hands and says Congress will need to decide.

A. The Proposals Fail to Define What Sector a New Sector-Specific Regulator Would Regulate

The scope of a sector-specific agency’s expertise relies entirely on the definition of the sector. Yet while the proposals can and do list the specific companies they want to regulate, they struggle to establish a principled definition for the “big tech” sector. With no principled sector definition, a new agency cannot achieve a comparative advantage—it cannot justify its existence.

1. The Importance of Defining a Sector

As Harold Feld succinctly argues, “sector-specific regulation requires a definition of the sector.”[32] By defining the sector we identify the expertise gap that we expect a new agency to fill. A sector definition identifies where a new agency will have a comparative advantage over Congress or existing agencies.

Feld also lays out a skeletal framework for how to define a sector. “[S]ector-specific regulation is premised on the idea that the sector has unique characteristics that differentiate it from other lines of commerce.”[33] Slightly more precisely, such characteristics “raise issues and concerns that are common to all” companies in the sector but which are “not wholly shared by other services” outside the sector.[34]

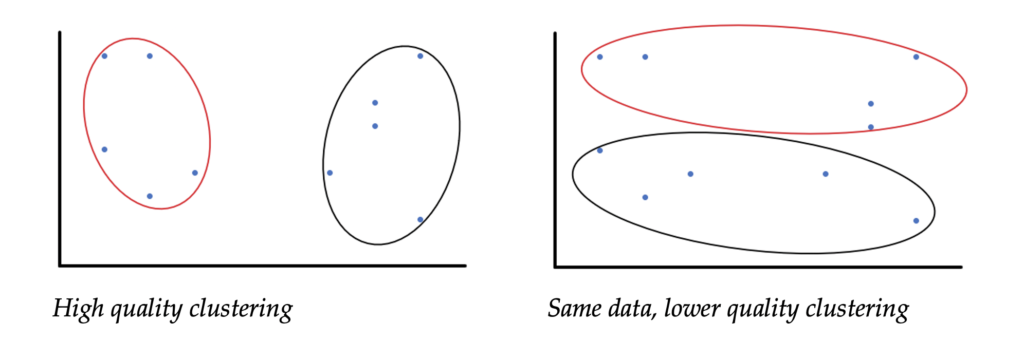

Data scientists call this “cluster analysis,” and this is a useful metaphor for our discussion. Given a set of items, identify a subset—a cluster—of items that are similar to one another and dissimilar to items not in the cluster. The more similar are items within a cluster and the more dissimilar they are to other items, the higher the quality of the clustering analysis.

The quality of clustering depends on the measure of similarity, that is, the way we determine whether two items are similar. In the charts above, similarity is based on proximity in a two-dimensional graph. When trying to cluster companies into sectors, some measures or “dimensions” that we might use to judge similarity include:

- inputs

- business model

- business process and

- outputs

Using these dimensions, for example, we might cluster all local bakeries into a sector but would exclude car dealerships because they offer very different products with unrelated inputs, business models, processes, and outputs.

These are just a few of an infinite number of dimensions on which one might compare companies. Others might include annual revenue; sales in the past ten years; height of average employee; first letter of company name. In fact, with any group of companies you could almost certainly find at least one shared characteristic.

So, it is not enough that a sector includes companies that are alike on some dimensions; they must also be distinct from other, non-sector companies on those dimensions. Sector definition matters because the further the sectors are “set apart”—the higher quality the clustering—the greater a comparative advantage for the resulting agency, and thus the stronger the efficiency justification for its creation. A low-quality sector definition makes it harder for an agency to specialize, weakens its comparative advantage, and therefore undermines its justification for existing. A high-quality sector definition strengthens the case for a new agency.

Finally, when defining the sector for a new agency, we must choose dimensions directly related to the concerns that we want the new agency to address. We are not just creating new agencies on a whim. We want them to be expert in solving certain issues and problems. Because the dimensions we choose identify what is unique about the sector, they determine where the agency has a comparative advantage. We would not group containerships and yellow rubber duckies under the same regulatory agency just because both float. Even if the “floats” dimension creates a high-quality clustering, an expertise in “floating” technology probably does not help address any regulatory problems we hope to solve.

To sum up, when defining a sector, we want a high-quality clustering of companies based on characteristics that directly relate to the issues in which the agency must be an expert.

2. The Difficulty of Defining the “Big Tech” Sector

Under this approach, how do the proposals fare in defining the “Big Tech” sector? On many dimensions, the companies that are most regularly lumped together differ significantly. Yet all the proposals identify characteristics shared by “digital platforms.” Several proposals connect those characteristics to competition issues—but those characteristics and thus those issues are also common in many other companies. Some of the proposals also list other, non-competition issues and problems for a digital regulator to address. But the proposals fail to demonstrate that such issues are related to the sector definition and thus susceptible to sectoral agency expertise.

As a result, the proposals offer low-quality definitions of the sector insufficient to justify a new, sector-specific regulator.

a. Tech Companies have Very Different Business Models, as the Proposals Acknowledge

Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Apple, and Facebook are frequently described as “tech companies.” Does this make them companies in the same sector? No. In fact, these are very different companies with very different core businesses. Microsoft sells operating systems and office productivity software. Google also offers a mobile operating system—which it gives away—but primarily sells search and interest-based advertising. Apple designs hardware and software and offers online services, such as the App Store and iTunes, where consumers can make purchases. Amazon runs an online marketplace, operates a variety of retail stores, and sells cloud-computing services. Facebook provides a variety of communication tools that allow users to post images, videos, and other content for their select audiences to communicate directly with other groups and individuals, and then sells advertising reaching this audience.[35]

One way to test whether companies are in the same sector is who they compete against. Amazon’s online retail site competes against eBay and Walmart more than it does against Facebook or Google. Apple’s core device business competes with hardware manufacturers around the globe, including Samsung, LG, and Sony. Perhaps the closest of the major tech companies are Google and Facebook, who are both major players in online advertising.

Another problem with defining the tech sector by the use of technology is that a wide and expanding category of businesses use these same technologies. In some sense, all companies are becoming tech companies.

In short, “tech” is not a sector. There is no general “tech” market or industry, or even a “digital platform” market or industry. Consumers are not searching for tech companies or digital platforms. In fact, these companies’ platforms serve very different consumer needs. Beneath the superficial similarity that these companies are big, use a lot of data, and often offer tools that connect people, defining the relevant industry is not so easy.

b. Tech Companies Share Characteristics with Each Other, but Also with Many Other Parts of the Economy

The proposals generally acknowledge that the big tech companies are quite different from each other.[36] But, as they point out, tech companies clearly share some characteristics. For example, the CMA report identifies the following common characteristics:

- network effects and economies of scale;

- consumer decision making and the power of defaults;

- unequal access to user data;

- lack of transparency;

- the importance of ecosystems; and

- vertical integration, and resultant conflicts of interest.[37]

The other proposals offer similar lists.[38] However, these dimensions cannot define a sector for the purposes of justifying a new agency. Many of these characteristics are common to all consumer-facing digital businesses, and many are also evident in non-digital businesses such as electronic payment systems,[39] airlines,[40] and even retail.[41] As the Stigler Center report, which offers a similar list, admits, “From an economic perspective, there is no single new characteristic that would make competition in digital platforms different from more traditional markets.”[42] Feld makes a similar point about his own slightly different list of characteristics, admitting “other successful (or even dominant) businesses [in other sectors] will replicate some of the features” of digital platforms, like Walmart did in expanding retail into groceries and pharmaceuticals.[43]

If these characteristics do not differentiate so-called digital platforms from other companies, what comparative advantage would a new agency possess? A general consumer protection and competition agency like the Federal Trade Commission has expertise in each of the characteristics the CMA lists. The FTC also has actual experience in evaluating these characteristics, including investigations of each of the GAFAM companies.[44] The FCC has less experience in consumer decision making, user data access, and transparency, but plenty of experience in the other dimensions, albeit in the telecommunications sector. The CMA factors do not differentiate these companies sufficiently to demonstrate a need for new expertise.

The Stigler Center report claims that the difference is in scale and overlap of these issues.[45] Similarly, the CMA argues that these characteristics are “mutually reinforcing and in combination provide an unassailable incumbency advantage.”[46] Thus the argument seems to be that a Digital Authority would specialize in the unique overlap of conventional expertise. However, existing agencies already in possession of that conventional expertise would seem to be well-positioned to study and specialize in the overlap of those areas of expertise.

c. None of the Proposals Define a Differentiated Sector that Justifies a New Expert Agency

Given the wide variation of tech companies’ business models, it is no surprise that the proposals struggle to define the sector which a new agency would regulate. Only one, Feld, makes a serious attempt to do so. The rest adopt definitions without any substantial justification—a narrow and specific definition, in the case of the CMA report, or expansive and vague definitions, as in the Shorenstein and Stigler reports.

While the CMA report lists some broadly applicable characteristics, as noted above, those characteristics are not how it defines the sector. Instead, perhaps recognizing the problems with sweeping such vastly different companies into the same sector, the CMA report focuses exclusively on “platforms funded by digital advertising.”[47] That definition includes the core businesses of Google and Facebook. But it excludes the core businesses of companies like Amazon and Apple, which the report characterizes as “transaction-based platforms.”[48] It also excludes Microsoft. This definition helps the CMA report narrow its analysis (it is by far the most empirical of the proposals). And this definition does offer a differentiated area of expertise. But the report does not explain why it drew the lines so narrowly. In fact, the exclusive focus on Google and Facebook suggests the CMA believes other big tech companies are in different sectors.

Of all the proposals, Harold Feld’s offers the most overt definition of digital platforms. In fact, as demonstrated above, Feld appears to have thought more deeply about the importance of a clear sector definition than have the others. Feld defines the digital platforms as services that:

- provide access through the internet,

- operate as multi-sided platforms that

- facilitate consumer-generated content and sell directly to consumers, and

- possess Reed or Metcalf network effects.[49]

This is a broad definition—certainly broader than CMA’s. But Feld’s definition still has ascertainable contours. For example, Feld argues that Netflix is not a digital platform under his definition because its primary business does not facilitate consumer-generated content.[50]

In a later section of his report, Feld notes that some attack the very premise of his proposal by arguing that “[d]igital platforms do not form a distinct sector of the economy” and that the characteristics of digital platforms that Feld identified “are merely aspects of a business model rather than features that define a sector in need of sector-specific supervision.”[51] In other words, they challenge his definition as a low quality clustering. Somewhat surprisingly, having acknowledged this fundamental challenge, Feld barely engages with it. He instead just flatly asserts that “[d]igital platforms are now a distinct sector of the economy that impinges on nearly every aspect of our lives.”[52] His lengthy discussion of how to define digital platforms does not offer much of a defense, either. The companies that fall under Feld’s definition of “digital platforms” do very different things. While the companies share some characteristics with each other, they also share these and other important characteristics with many other companies. In short, his sector definition lacks differentiation.

Another way to highlight the low-quality clustering of Feld’s definition is to consider the scope of problems he expects a new agency to address. Feld would charge a new digital agency with a wide range of different responsibilities: competition, privacy, content moderation, promotion of diverse viewpoints, public safety, disability access, and consumer protection, among others. What does this enormous range of issues have to do with the dimensions of Feld’s sector definition? Feld does connect his definition to competition issues, arguing that the features of his definition “potentially create enduring market power in ways that challenge modern antitrust analysis.”[53] But he fails to connect his sector definition to any of the other areas the new agency would regulate. Why, for example, would an agency expert in multi-sided platforms have a comparative advantage in addressing privacy concerns or free speech concerns? Feld does not say.

Indeed, Feld is not particularly confident in the definitiveness of his definition. He admits that “[t]he shape of the sector may not become clear for some time, and Congress may need to revisit its initial decision.”[54] Given that “sector-specific regulation requires a definition of the sector,” it would seem prudent to seek an alternative to a sector-specific regulator while the shape of the sector remains unclear.[55]

The Stigler and Shorenstein proposals are not nearly as selective as the CMA or Feld proposals, instead offering very broad, almost unbounded definitions. Such broad sector definitions offer little guidance as to the expected expertise of the proposed new agency.

The Shorenstein Center’s report defines the regulated industry as “consumer-facing digital activities of companies with significant strategic market status.”[56] This broad category arguably includes any large consumer company with an online presence, and almost certainly retailers like Walmart and Target. Can any agency be an expert in such a wide swath of the economy? The expertise required is even broader when one considers that determining “significant strategic market status,” will require the agency to understand the markets more generally; they cannot focus only on the biggest companies.

The Stigler Center recommends “establishment of a sectoral regulator” called the Digital Authority (DA) to govern “Digital Platforms,” which it acknowledges “lacks a consistent definition” but under which it includes Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft.[57] The report argues that the DA’s “scope of regulatory power . . . must include digital businesses that facilitate transactions of any kind (including the sale of advertising).”[58] And “in order to prevent firms subject to regulation from evading its oversight,” the DA needs “broad authority over digital business models. . . .”[59] It is difficult to identify any online business that doesn’t fall within these broad definitions.[60] To “specialize” in such a broad swath of online activity is to not specialize at all.

Perhaps the difficulty that these proposals face in defining a sector is not surprising. Since each proposal argues that these companies have significant or even dominant market power, they must walk a tightrope. Claiming that these companies are part of same industry suggests that they compete, undermining such allegations of market power. However, acknowledging that the companies serve different markets suggests there may not be a common expertise that would justify a new agency. Still, no proposal for a new agency can make a compelling case for a new regulator without adequately defining the sector to be regulated, and none of these proposals do.

B. The Proposals Fail to Explain Why Enhancing Existing Agencies is Inadequate

Existing agencies already have expertise relevant to the issues that the proposals raise. Notwithstanding this, each proposal argues that current agencies lack the resources, expertise, or authority to govern the relevant companies.[61] But only two of the proposals expressly argue that such resources, expertise, and authority would be best deployed in a new agency—and one of those, Feld, concludes that, while desirable, a new agency probably is not politically feasible.

1. The Shorenstein Center Seeks a Novel Regulatory Approach that Could Work in a New Agency—but Could Also Work in an Existing Agency

The Shorenstein Center report unequivocally argues that we need a new agency. We should “not bolt on authority to an existing agency,” the report argues, because “[e]xisting agencies, as a result of their statute, staff, tradition and jurisprudence are infused with an inherently analog DNA” when what is needed is “digital DNA.”[62] “Old agencies (even if their statutes are updated) are saddled with legacy precedents . . . ,” it claims.[63] Existing agencies are also stretched thin executing their current duties. Therefore, “[r]ather than bolt on to and dilute an existing agency’s responsibilities, it is preferable to start with a clean regulatory slate and specifically established congressional expectations.”[64]

The core of the Shorenstein Report’s case for a new agency, then, boils down to the claim that “digital oversight must be different.”[65] Different how?

What sets the DPA apart from traditional agencies is twofold: (1) its combination of agile regulatory operations with the kind of public participation required in the APA, and (2) its focus on concerns that flow from network effects, the power of data collection and exploitation, and the winner-take-all nature of digital platforms.[66]

Applying the taxonomy of agency expertise set out previously, the first invokes process expertise (how the agency will regulate) and the second invokes industry expertise (what or whom the agency will regulate). We have already looked at the Shorenstein report’s weaknesses in identifying industry expertise: the report defines covered entities so broadly as to offer little insight into what new expertise a new agency would bring.

What about the need for new process expertise? The authors propose an entirely “new approach to regulation.”[67] This approach has at least three serious internal tensions. First, it criticizes using “statutory expectations established in the industrial era” to regulate novel digital platforms yet would impose common law principles that are much older—and already apply to these companies.[68] Second, common law principles are flexible specifically because courts apply them ex post, on a case-by-case basis; yet the report laments a lack of ex ante rules and calls for the new agency to regulate.[69] Finally, the report proposes to keep up with fast-changing digital technology through “agile regulatory operations” that would “supplement the traditional notice and comment rule-making of a federal agency.”[70] The report details this workflow but does not explain how adding a layer of procedure to the current rulemaking process would expedite that process.[71]

Still, regardless of whether this new approach would be effective, it certainly would require a novel kind of procedural expertise. Existing agencies have some relevant experience: the FTC has expertise in applying broad standards in a flexible manner, and other agencies such as the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (“NTIA”) have expertise in stakeholder consensus processes. But no existing agency would have a substantial comparative advantage over a new agency in implementing this new regulatory approach.

The Shorenstein report specifically rejects the Federal Trade Commission as a candidate for new authority, but its arguments are not strong. The report argues that the FTC is not suited to governing digital platforms because its authority has been constrained by Congress in the past.[72] But creating a new agency would also require an act of Congress. The report does not explain why Congress would rather embrace and sustain a new agency with broad authority rather than expand the FTC’s authority. The report further claims that “the FTC’s resources are already spread thin.”[73] This criticism also rings hollow. In fact, it would be easier for Congress to allocate additional funds and resources to an established agency than it would be to structure and fund a new agency.

The Shorenstein report makes a related but distinct argument that “add[ing] oversight of digital platform activities to [the FTC’s] portfolio would defocus the agency from its essential tasks.”[74] Implicitly, the report is acknowledging that agencies charged with deploying many different, unrelated types of tasks have little comparative advantage over more focused distributions of responsibilities. The Shorenstein proposal itself is vulnerable to this criticism, given the amorphous definition of the sector it wants to regulate and the vast range of problems its preferred digital regulator would cover. But given the broad expertise required for the Shorenstein center’s proposed agency, there would be overlap with the FTC’s competition and consumer protection missions, offering mild synergies.

In sum, the Shorenstein report makes a plausible case that a new agency could build a comparative advantage in process expertise. The question, then, is whether any benefits of this novel process expertise in a new agency outweigh the detriments of a poorly defined industry expertise that overlaps with expertise in existing agencies.

2. Harold Feld’s Argument for a New Agency Hinges on His Problematic Sector Definition, and Even He Gives it Up

In his proposal for a “Digital Platform Act,” Harold Feld argues that existing federal agencies lack the expertise to regulate the largest digital platforms, and that “the cleanest solution to the question of implementation is to start fresh.”[75]

Feld compares three options: amending the Federal Trade Commission, amending the Federal Communications Commission, and starting fresh with a new agency. Again, Feld puts forth the most thoughtful analysis of the proposals. As he notes, “any agency—whether existing or created for the purpose of implementing and enforcing the DPA—will need to hire new staff and acquire new skills.”[76] The question is which approach will be “cheaper and more effective” at implementing his recommendations?[77]

Feld advances four arguments for a new agency. Three depend on the unfounded assumption that the sector has been clearly defined. First, he argues that a new agency would have “fresh eyes” with which to view the unique characteristics of companies in the sector.[78] Even if novice observation were preferable to experience, this assumes there are unique characteristics that identify these companies. But as discussed earlier, every elements of Feld’s digital platform definition also characterizes companies in other identifiable sectors—there are no unique characteristics for a new agency to specialize in. At best, there may be a unique overlap of characteristics. Second, he argues that a new agency would not be distracted by issues outside of this important sector. But because the characteristics that define this “sector” are not unique and therefore other agencies already have relevant expertise, it would be a benefit, not a distraction, to bring such expertise to bear. Third, he claims that a new regulator dedicated entirely to digital platforms would be better at identifying and carefully judging the differences between various platforms. This could be true if the sector was sufficiently distinct so that a new agency could develop a comparative advantage. But Feld’s sector definition overlaps sufficiently with the expertise of other agencies that it is not obvious that a new agency would be more discerning.

Feld also argues that “[t]here is already more than enough work to justify creation of a separate agency.”[79] But the volume of work cannot alone justify the creation of a new agency rather than expanding an existing agency.

In any case, Feld observes that a new agency faces difficult political barriers due to greater expense and potential jurisdictional battles with existing agencies. Expanding the jurisdiction of the FTC or the FCC (Feld’s preference) might be more plausible. Ultimately, he concludes that “[r]ather than rushing to answer the question, Congress should instead focus on drafting a suitable, comprehensive Digital Platform Act and then determine based on the content of the DPA which path to follow.”[80]

* * *

In sum, the proposals fail to make a compelling positive case for a new agency to regulate big tech. They struggle to even define the to-be-regulated sector, leaving it unclear what expertise the new agency would develop. The two proposals that make a case for a new agency (rather than just suggesting it as a possible alternative) offer benefits of a new agency that are, at best, very slight and mostly speculative.

IV. An Agency Focused on Big Tech Would Make Things Worse

The proposals offer only the slightest reason to believe that a new agency to regulate big tech would be superior to other reforms, such as modifying existing agencies. Most do not at all consider the risks of creating a new agency; a few do, but only in passing. Yet there are good reasons to worry that creating a new big tech regulatory agency would actually make things worse by leading to regulatory capture and by wasting taxpayer money.

A. A “Big Tech” Regulator Would be Captured by Big Tech

The biggest problem with creating a specialized agency is that such agencies are more vulnerable to regulatory capture. Instead of creating a new, separate agency to regulate big tech, Congress should assign any new authority and expertise to existing agencies, particularly to generalist agencies like the Federal Trade Commission, which—as even the Stigler Center report acknowledges—have proven relatively resistant to regulatory capture.[81]

1. All Agencies Tend Toward Capture

The basic idea of regulatory capture was explained by Nobel Memorial Prize-winning economist George Stigler, who argued that “regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefit.” In his foundational paper, “The Theory of Economic Regulation,” he warned that any regulated industry has strong incentives to form close connections with its regulators to seek favors. The inevitable result is that the industry disproportionately influences the agency’s agenda, shapes its rulemaking and even supplies it with personnel.[82] Captured agencies do not hold companies accountable; instead, they act to benefit the industry’s established players, disadvantaging newer firms and the public at large.

The forms and causes of regulatory capture vary, and regulatory capture is nearly always a question of degree.[83] The most egregious forms of regulatory capture are government “oversight” organizations occupied and controlled by the regulated entities themselves. For example, state boards responsible for setting the rules for the practice of dentistry should not be (but often are) dominated by practicing dentists.[84]

But regulatory capture occurs even when agencies are populated by government officials who are independent. Public choice scholars have explained how agency leaders will act in rational self-interest by seeking to keep their position and to expand the power and budget of the agency and to secure prestigious or profitable positions after leaving leadership.[85] This requires currying favor with influential politicians and powerful interest groups, usually by employing the tools of the regulator in favor of those groups’ interests.[86]

Capture can happen in less cynical and more subtle ways. Agency expertise requires experience or long-term interest in the regulated industry, and individuals with that background will tend to view issues from the perspective of that industry, want that industry to thrive, and draw information from industry sources. “Thus, even a benign, well-intentioned industry expert will be inclined to render decisions that favor the industry he regulates.”[87]

Regulatory capture undermines the agency’s oversight mission, shifting the benefit away from the public and toward the regulated industry. Perhaps most concerning, regulated incumbents can use the power of the captured agency to establish a significant barrier against competition. For example, industry participants might directly convince regulators to subsidize their businesses, giving them an advantage against would-be competitors. More subtly, large firms might support costly compliance regimes that disproportionally disadvantage smaller firms. In either case, this type of “public competition” is a particularly pernicious type of rent-seeking.[88]

Even absent overt acts by the regulated firms, regulation and incumbent business models will naturally co-evolve to fit each other. Disruptive business models that do not fit into the current regulatory boxes will face significant regulatory risks in this circumstance. Some have called this the “procrustean problem” of regulation after the ancient Greek myth in which a rogue blacksmith stretches or amputates human visitors to fit his iron guest bed.[89] Regulators need to fit and classify companies according to regulatory categories, and this naturally benefits incumbent business models while disadvantaging novel and experimental approaches.

This type of regulatory capture creates a status quo bias. The mismatch between existing regulation and a new business model can mean that innovative ways of accomplishing certain goals may be legally risky to pursue not because they are dangerous or harmful but because they were not contemplated when the regulation was developed. At best, innovators in this situation will have to educate regulators and potentially pursue regulatory changes. At worst, innovators will be warned off by their lawyers and investors, will choose to pursue less legally uncertain endeavors, and the agency will not even know the chilling effect its framework is having.

2. The Risk of Regulatory Capture is Higher for Specialized Agencies

Regulatory capture is a problem that all agencies face. However, a sector-specific regulator of big tech is more likely to be captured than are generalist agencies like the Federal Trade Commission.[90] Yale Law Professor Jonathan R. Macey examines this issue in depth in his article, “Organizational Design and Political Control of Administrative Agencies,” where he analyzes the outcomes from “the most fundamental choice of agency design: whether to create a single industry regulatory agency or a multi-industry agency.”[91] As he explains:

Where a regulatory agency represents a single ‘clientele,’ the rules it generates are far more likely to reflect the interests of that clientele than the rules of an agency that represents a number of clienteles with competing interests.[92]

That is, the smaller the number of companies under a regulator’s jurisdiction, the easier it is for those companies to capture the regulator. This is because the pressures toward regulatory capture are amplified for more specialized agencies. Although James Madison was comparing forms of national government rather than forms of agencies, his discussion of factions in Federalist 10 helps explain why narrowly specialized agencies face heightened risks of capture:

[T]he fewer the distinct parties and interests, the more frequently will a majority be found of the same party; and the smaller the number of individuals composing a majority, and the smaller the compass within which they are placed, the more easily will they concert and execute their plans of oppression.[93]

In other words, a small group with similar interests and perspectives can more easily bend government action to its benefit. When a small interest group has a dedicated regulator, the risk of regulatory capture is at its peak. “The interest group that is regulated by a single regulatory agency will be able to influence that agency to a far greater extent than the interest groups that must ‘share’ their agency with a variety of other interest group,” argues Professor Macey.[94] By contrast, government actors with jurisdiction over a wide range of conflicting interests are “beholden to many but captured by none.”[95]

Incumbents regulated by a specialized agency can more easily weaponize regulation against new competitors, often with the regulator’s help. Competitive threats to a sector also threaten the sector-specific regulator. In fact, “[t]he creation of administrative agencies helps insure against an industry’s obsolescence by creating a regulatory body with incentives to pass rules that increase the probability of the industry’s survival,” Macey explains.[96] For instance,

[L]ong after there was any economic need for a savings and loan industry, thrift regulators took extraordinary steps to ensure the industry’s survival. The regulators acted as they did, not to further the public interest, but because they understood that the survival of the industry was crucial to their own professional survival.[97]

In such situations, outside innovators can face a unified front of incumbents and regulators seeking to control disruption in their own interest, not in the public interest. This weaponization of a regulatory agency by incumbents is particularly harmful in industries with the potential for rapid and disruptive innovation, where the existential threat is heightened.[98]

For these reasons, the decision to create a new, sector-specific agency should not be taken lightly. “[T]he ability to structure the initial design of an agency,” Macey argues, “may well be the most powerful device available to politicians and interest groups” to shape the future path of an agency after its creation.[99] Specifically, when Congress chooses between a “single-interest” or “multi-interest” design for an agency, it affects which groups will be influential repeat dealers and which will be infrequent and thus less influential.[100] Macey compares single interest agencies like the Securities and Exchange Commission with multi-interest agencies like the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. He provides example after example of the SEC, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission and other sector-specific agencies serving the interests of the firms they regulate.[101]

Establishing a sector-specific agency comes with significant risks that the agency will serve the interests of the regulated industry rather than the public interest. In contrast, “[t]he FTC, unlike industry specific regulatory bodies, deals with industry in general. Perhaps this explains why, at least to date, we are unaware of claims that the FTC has been captured by any industry or special interest group.”[102]

3. The Proposals Offer No Defense from Capture—and One Proposal Appears to Encourage It

Regulatory capture is the biggest risk in creating a new sector-specific regulator. But the proposals hardly address this risk; when they do, they offer superficial solutions; and one proposal seems almost purpose-built to encourage regulatory capture. If the proposals honestly grappled with the risk of regulatory capture, their arguments for a new agency would be more persuasive. As it is, however, they have only counted the benefits and ignored the single biggest cost.

Neither the CMA report nor the Shorenstein report even mention regulatory capture. Feld’s disdain for the language of public choice theory fairly oozes from the pages of his proposal; he only refers to “agency capture” to dismiss it as “dogma” or as an “outsized influence on public policy.”[103] He does raise capture concerns about embedding the digital regulator within the FCC, although he doesn’t use that language.[104] But he does not mention any potential concerns about regulatory capture of a new agency.

The Stigler Center (yes, named after the father of regulatory capture studies, George Stigler) does only marginally better. It eagerly recommends a new agency throughout the body of the report.[105] It expresses generic capture concerns in a few locations.[106] But the only mitigation it suggests is a two-sentence fix in the cover Policy Brief.[107] That proposed fix: transparency and “at least initially—to have the Digital Authority as a subdivision of the FTC, an across-industry authority with a better-than-average record of avoiding capture.” That is, the Stigler Center recommends fixing regulatory capture concerns of a new agency by abandoning the recommendation of a new agency. While the report deserves credit for reaching a reasonable conclusion, I have argued separately:

This is not strong evidence of a thoughtful approach to regulatory capture. Instead, . . . this tack-on paragraph looks more like someone raised last-minute concerns that George Stigler might have objected to creating an entire new agency.[108]

In further evidence of a failure to grapple with the challenge of regulatory capture, the Stigler Center report claims that the FCC “may offer the best guidance for how to approach public accountability for digital platforms.”[109] Several of the other proposals also draw upon the example of the FCC.[110] Yet the history of the FCC is a history of regulatory capture. At nearly every turn, with every new potentially disruptive communications innovation, the FCC (and its predecessor, the Federal Radio Commission) did the bidding of the best-connected incumbents. As I have written elsewhere,

For example, almost immediately after its creation, the Federal Radio Commission sided with industry players when it rejected the expansion of AM radio bands at the behest of existing commercial broadcasters. Later, the agency slowed the development of FM radio to protect AM radio manufacturers. It cracked down on early “community antenna television” (cable TV) to protect the broadcast television industry; conducted “beauty contests” to parcel out valuable broadcast licenses, sometimes to the politically connected (such as President Lyndon Johnson’s wife); and slowed approvals and imposed onerous regulations on satellite radio services to protect traditional radio stations.[111]

As former FCC chairman Michael Powell said, “[T]he history of the FCC is, when something happens that it doesn’t understand, kill it. We tried to kill cable. We tried to kill long-distance. When [MCI founder] Bill McGowan start[ed] stringing out microwave towers that threatened AT&T, the FCC tried to stop him. The FCC tried to kill cable because it was going to threaten broadcasting.”[112] While the FCC didn’t completely halt technological progress or competition, it often slowed progress for years, and occasionally by decades.[113]

The Stigler Center report briefly acknowledges the FCC’s long and sordid history of regulatory capture but offers no suggestions for how to prevent that history from reoccurring in a digital regulator.[114]

But while the other proposals largely pretend regulatory capture does not exist, the Shorenstein Center report almost seems to actively embrace it. The report suggests an architecture for a Digital Platform Agency (DPA) that appears particularly vulnerable to regulatory capture for two reasons. First, it encourages personnel likely to have broad alignment with industry. The report calls for the DPA to be led by commissioners and staff with “digital DNA,” that is, subject matter expertise as well as management experience.[115] The largest source of these types of individuals will be from industry, of course, and as discussed earlier even independent-minded individuals with this kind of background will still tend to operate within the industry paradigm.[116]

Second, it proposes a cooperative regulatory model that will inherently benefit incumbents. To “mitigate[e] the traditional complaint of regulatory overreach and lack of agility” the Shorenstein Report proposes that a “Code Council” of industry and public representatives cooperatively develop codes of behavior for digital companies.[117] Such codes would be then circulated for public comment on an accelerated timeframe and then considered by the DPA commissioners for adoption as binding rules. Giving private interests an elevated role in rulemaking and the ability to set the agenda while compressing the time for public review likely increases the already significant risk of regulatory capture that this kind of sector-specific agency would face. Indeed, this proposal sounds similar to the “offeror process” that Congress created for the Consumer Product Safety Commission—a process that was so “dominated by industry” that “Congress viewed [it] as a failure and abolished it.”[118]

Several of the proposals acknowledge that a new digital regulator would share jurisdiction with other agencies, particularly the antitrust agencies, and that this would require the various agencies to coordinate with each other. But if Congress creates such jurisdictional conflicts, it may generate a new problem. As Professor Macey puts it, “these conflicts tend to align the interests of the regulatory agency with the firms it regulates.” [119] In other words, a digital regulator would have strong incentives to expand its jurisdiction at the expense of other agencies—and this expansion is in the regulated firms’ interest as well. It could be that the new digital regulator becomes big tech’s biggest defender from antitrust enforcement.

B. A New Regulator Would Be Unnecessarily Expensive

Creating an entirely new agency would also be costly in practical dollar terms. Many of these are straightforward administrative costs. Compared to enhancing an existing agency, creating a new agency would have significant start-up costs as well as duplicative ongoing expenses. These costs can be substantial. Money that could be allocated to substantive roles would instead pay for staff and resources that support the substantive work at the new agency. (For example, around 20% of Federal Trade Commission employees are support or management.[120]) And the flip side of starting with a clean slate is that a new agency has little or no experience to draw upon. To the extent the experience that is missing is related to the specific new problems the agency is intended to solve, the new agency is not disadvantaged relative to other agencies. Yet there are many other types of experience, including administrative procedures, human relations, press relations, litigation, and others where a new agency will need to build institutional competencies.

More substantively, creating a new agency with a mission and jurisdiction that overlaps with one or more existing agencies will incur several other types of costs. If both agencies retain jurisdiction, there will be coordination costs on future investigation, enforcement, and regulation. If the new agency displaces the old agency’s jurisdiction, there will be the cost to transfer knowledge and talent from the old agency to the new one.

This overlap cost is highest for the broad proposals like Feld’s and the Stigler Center, which envision a new agency that comprehensively regulates the subject companies on everything from privacy to antitrust to content moderation. Given that there are already agencies that specialize in many of those issues, the overlap will be significant and eliminating or accommodating it will be costly.

For example, the Federal Trade Commission has for twenty years been the primary federal protector of consumer privacy, bringing hundreds of enforcement actions, including against many of the biggest tech companies.[121] If, as the Stigler Center report suggests, a new regulator would address these issues for the biggest tech platforms, there would be a complicated series of negotiations necessary to hand off governance from the FTC to the new agency. Transferring personnel from the FTC to a new agency would create its own problems. For example, because the FTC is responsible for enforcing privacy across the entire economy, cannibalizing its staff to create an agency focused only on the privacy of some subset of internet companies would leave the FTC shorthanded as it protects privacy in every other sphere of the economy.

Conclusion

I noted early on in this chapter that these proposals were generally ambivalent about creating a new agency. It turns out this is for good reason: there are few benefits and significant risks. A new agency may have a mild comparative advantage in procedural expertise if an entirely new regulatory approach is adopted. Still, it will be very difficult to find that expertise and establish a focused mission for a regulator of such a diverse and dynamic collection of companies. To the extent additional expertise is needed for regulation, it can more easily and more efficiently be placed in existing agencies, especially generalist agencies. Perhaps most importantly, a new agency specialized on big tech would be more vulnerable to capture than existing generalist agencies. And finally, the practical costs of creating and maintaining a new agency would be higher than enhancing existing agencies.

In short, “big tech” might need new regulation; but it does not need a new regulator.

Footnotes

[1] See, e.g., Alina Tugend, Fervor Grows for Regulating Big Tech, N.Y. Times (Nov. 11, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/11/business/dealbook/regulating-big-tech-companies.html.

[2] See, e.g., Ben Brody, Momentum Grows for a Digital Watchdog to Regulate Tech Giants, Bloomberg (Sept. 11, 2019), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-09-11/momentum-grows-for-a-digital-watchdog-to-regulate-tech-giants.

[3] Competition & Markets Auth., Online Platforms and Digital Advertising (July 1, 2020), https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5efc57ed3a6f4023d242ed56/Final_report_1_July_2020_.pdf (Hereinafter “CMA Report”). This report builds on a March 2019 report from the Digital Competition Expert Panel, led by economist Jason Furman, which also recommends a Digital Marketing Unit and is likewise agnostic as to whether the DMU is a new agency. Unlocking Digital Competition: Report of the Digital Competition Expert Panel 10, 55 (Mar. 2019), https://assets.publishing.

service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/785547/unlocking_digital_competition_furman_review_web.pdf

[4] CMA Report, supra note 3, at ¶¶ 69, 74 (describing platforms with ‘strategic market status’); see also id. ¶¶ 7.54-7.55 (based on Furman Review definition).

[5] Id. at ¶ 76, 7.20.

[6] Id.

[7] Stigler Ctr.., Stigler Committee on Digital Platforms Final Report (2019), https://research.

chicagobooth.edu/-/media/research/stigler/pdfs/digital-platforms—committee-report—stigler-center

.pdf?la=en&hash=2D23583FF8BCC560B7FEF7A81E1F95C1DDC5225E (Hereinafter “Stigler Report”).

[8] Id. at 32 (“Therefore, the report suggests that Congress should consider creating a specialist regulator, the Digital Authority.”); id. at 100 (“For the reasons above, we believe the establishment of a sectoral regulator should be seriously considered.”); id. at 120 (“Finally, because the problems we identify may require action beyond antitrust, we also propose the establishment of a new digital regulatory agency, or Digital Authority.”).

[9] Id. at 18.

[10] Luigi Zingales & Fiona Scott Morton, Why a New Digital Authority Is Necessary, ProMarket (November 8, 2019), https://promarket.org/2019/11/08/why-a-new-digital-authority-is-necessary/.

[11] Harold Feld, The Case for the Digital Platform Act, Public Knowledge at 20 (May 2019), https://www.publicknowledge.org/assets/uploads/documents/Case_for_the_Digital_Platform_Act_Harold_Feld_2019.pdf.

[12] Id. at 16.

[13] Id. at 178.

[14] Id. at 72 (“To assure that the enforcing agency has all the necessary tools at its disposal to address a field as diverse, dynamic, and essential to our economy as digital platforms, Congress should make the authority of the agency to consider even the most draconian solutions crystal clear.”).

[15] Tom Wheeler et al, New Digital Realities; New Oversight Solutions in the U.S.: The Case for a Digital Platform Agency and Approach to Regulatory Oversight, Shorestein Ctr. (Aug. 2019), https://

shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/New-Digital-Realities_August-2020.pdf.

[16] Id. at 17.

[17] Id. at 19.

[18] Id.

[19] Id. at 20.

[20] Paul M. Barrett, Regulating Social Media: The Fight Over Section 230 – and Beyond, NYU (Sept. 2020), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b6df958f8370af3217d4178/t/5f58df637cbf80185f372776/1599659876276/NYU+Section+230_FINAL+ONLINE+UPDATED_Sept+8.pdf.

[21] Hal Singer, Testimony to House Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law, at 4 – 5 (Mar. 30, 2020), https://www.econone.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Singer-Letter-to-Chairman-Cicilline-and-Ranking-Member-Sensenbrener.pdf (Hereinafter “Singer Testimony”).

[22] Id. at 4.

[23] Kevin Caves & Hal Singer, When the Econometrician Shrugged: Identifying and Plugging Gaps in the Consumer Welfare Standard, 26 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 395, 415-416 (2018) (arguing that the tribunal could apply a single standard to ISPs and tech platforms alike).

[24] Singer Testimony, supra note 21. at 4-5.

[25] Feld, supra note 11, 192, 194 (“[T]he cleanest solution to the question of implementation is to start fresh,” but “[i]f Congress wishes to build upon existing agencies, the logical choice is the FCC.”).

[26] Stigler Report, supra note 7, at 18.

[27] CMA Report, supra note 3, at 22 (“We use the term DMU very broadly, noting that this could be a new or an existing institution, or even that the functions could be assigned across several bodies.”).

[28] Wheeler et al, supra note 15, at 18.

[29] Jonathan R. Macey, Organizational Design and Political Control of Administrative Agencies, 8 J. L., Econ, & Org. 93, 103; Rachel E. Barkow, Insulating Agencies: Avoiding Capture Through Institutional Design, 89 Texas L. Rev. 15, 19 (“The classic explanation for agency independence is the need for expert decision making.”).

[30] For example, the Consumer Product Safety Commission, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Food and Drug Administration, Food Safety and Inspection Service, and Federal Communications Commission all advance similar consumer protection goals in their respective industries.

[31] See, e.g., Neil Chilson, How the FTC keeps up on technology, Fed. Trade Comm’n (Jan 4, 2018), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/blogs/techftc/2018/01/how-ftc-keeps-technology.

[32] Feld, supra note 11, at 4.

[33] Id. at n.176.

[34] Id. at 31.

[35] See David S. Evans, Why the Dynamics of Competition for Online Platforms Leads to Sleepless Nights But Not Sleepy Monopolies, (August 23, 2017), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3009438. Outside of these core businesses, these companies are broadly diversified. They have many lines of business—many of which compete with other large firms across the economy. For example, Amazon provides an online shopping and logistics company. But it also runs a major cloud services and internet infrastructure company, AWS, which shares little business model DNA with its consumer shopping site, yet which competes against offerings from Oracle, Google, Microsoft, and others. Microsoft also owns the business-focused social media platform LinkedIn. Facebook offers hardware VR devices through Oculus. Google is researching self-driving cars. Amazon owns Whole Foods, a grocery store.

[36] Feld, supra note 11, at 31; Stigler Report, supra note 7, at 7.

[37] CMA Report, supra note 3, at 11.

[38] Feld, supra note 11, at 21 (defining digital platforms as those that provide access through the internet, operate as multi-sided platforms that facilitate consumer-generated content and sell directly to consumers, and possess Reed or Metcalf network effects); Wheeler et al, supra note 15, at 36-37 (“[D]igital platforms are different,” because they “galvaniz[e] the power of network effects, economies of scope and scale, and massive amounts of data.”); Stigler Report, supra note 7, at 34 (“[T]he platforms with which this report is most concerned demonstrate extremely strong network effects, very strong economies of scale, remarkable economies of scope due to the role of data, marginal costs close to zero, drastically lower distribution costs than brick and mortar firms, and a global reach.”).

[39] Seth Priebatsch, The Hidden Monopoly Behind All Those Whizbang New Ways to Pay for Stuff, Fast Company (Apr. 10, 2013), https://www.fastcompany.com/3008076/hidden-monopoly-behind-all-those-whizbang-new-ways-pay-stuff.

[40] David Koenig & Scott Mayerowitz, Analysis: Consolidation of U.S. Airline Industry Radically Reducing Competition, Skift (Jul7 14, 2015), https://skift.com/2015/07/14/analysis-consolidation-of-u-s-airline-industry-radically-reducing-competition/.

[41] Monopoly by the Numbers, Open Markets, https://www.openmarketsinstitute.org/learn/monopoly-by-the-numbers. (listing 36 other industries with market concentration concerns).

[42] Stigler Report, supra note 7, at 34.

[43] Feld, supra note 11, at 34.

[44] “GAFAM” stands for “Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, and Microsoft.”

[45] Stigler Report, supra note 7, at 34.

[46] CMA Report, supra note 3, at 11.

[47] Id. at 5.

[48] Id. at 43.

[49] Feld, supra note 11, at 21.

[50] Id. at 31.

[51] Id. at 190-91.

[52] Id. at 191.

[53] Feld, supra note 11, at 36-41. Analysis elsewhere in this report responds to the substance of that argument.

[54] Id. at 190.

[55] Id. at 4.

[56] Wheeler et al, supra note 15, at 16.

[57] Stigler Report, supra note 7, at 7, 100.

[58] Id. at 105.

[59] Id.