Introduction

There have been many calls to replace or at least supplement the existing system of litigation based antitrust under the rule of reason with ex-ante regulation as a way to control anticompetitive behavior by large technology and platform firms.[1] This chapter first analyzes and explains some potential ways to distinguish ex-ante sector regulation from antitrust and competition systems based upon ex-post liability. While many have proposed that ex-ante regulation should be used in lieu of current litigation based antitrust law, this narrative is a false one—antitrust law and its institutions, throughout its history and including the present, has incorporated features of ex-ante regulations in both its laws and institutions.

Indeed, many of the proposed ex-ante approaches use traditional antitrust concepts that incorporate some components of proposals for ex-ante regulation. These include the use of ex-ante determinations of inherently and commonly unreasonable practices subject to per se condemnation, use of quick look or truncated analyses under the rule of reason, procedural changes dependent on prior information, such as the adoption of antitrust presumptions and changes to the standard of proof and the burden of proof.[2] Indeed, the recent history of the antitrust laws and the incorporation of economics into antitrust law has resulted in the replacement of unsupported presumptions and per se rules with a rule of reason analysis that evaluates the impact of a challenged behavior on competition. However, antitrust law also recognizes that not all antitrust inquires require the same degree of fact-gathering and analysis, and currently incorporates truncated forms of analysis under the rule of reason and presumptions when supported by the evidence.[3]

Other proposals would go beyond the existing bounds of antitrust and use an approach based on ex-ante sector regulations used to control natural monopolies.[4] This chapter focuses specifically on the choice to use sector-based regulation and/or antitrust to regulate competition and the implications that follow from that choice. In theory, the initial assignment of tasks between antitrust and sector regulation should reflect the comparative advantage of each regulatory approach, including the competence of the institutions set up to administer the regulatory regime.[5] The chapter applies this principle to explain why antitrust is a relatively poor framework for price regulation and affirmative duties to deal with rivals. Based upon comparative advantage, regulation of price and affirmative duties to deal are best left to sector regulators with industry specific expertise enforcing specific ex-ante regulations containing specific duties.

We then analyze the legal and economic interaction between the antitrust laws and sector regulation. In particular, when sector regulation and the antitrust laws are used to regulate competition, the two regimes can generate conflicts. In such cases, the application of antitrust law can be limited by the implied immunity doctrine and similar judge made regulatory immunities. Similar limits on the antitrust laws apply to conflicts between the federal antitrust laws and state regulations, which are controlled by the state action doctrine. While the implied immunity doctrine and many state action cases often illustrate the case where competition displacing regulations substitute for antitrust law, antitrust and sector regulation also can serve as complements.[6] Antitrust law can be applied to control deregulated portions of an industry and can serve to fill unspecified gaps in the regulation. Antitrust law is also used to constrain industry capture and other public choice problems generated by sector regulations.

However, even in the case of antitrust and regulation as complements, limits on antitrust are still important, as it is critical that each regulatory approach is limited to operate in a way that supports its ex-ante assigned function. The importance of sensible limits on antitrust and sector regulation is magnified by the Court’s expansion of the implied antitrust immunity doctrine that forces antitrust and regulation to function as substitutes in potential overlap areas. Moreover, achieving the right balance between antitrust and regulation in practice can be a challenging, long, and error filled process. The chapter illustrates the frictions in the economic and legal relationship between antitrust and regulation by examining the application of the antitrust laws to the conduct of pharmaceutical companies whose patents have been challenged under Paragraph IV of the Hatch-Waxman Act. The Hatch-Waxman Act represents one of the most visible forms of sector regulation of innovation. In particular, the Act, along with state generic substitution laws (GSLs), attempts to craft a specific solution to the use/creation tradeoff through specific modifications of the patent laws and the competitive relationship between branded drugs and firms producing generic versions of the drug. The imperfect regulatory structure generates incentives which are not intended or foreseen by those drafting the statute, which is first addressed through antitrust litigation, and then legislation to reallocate the assignment of tasks between antitrust and regulation. The history of the Act and State GSL illustrates the complex and evolving relationship between imperfect regimes as well as the difficulty of designing beneficial regulatory structures to control competition.

I. Ex-Ante Regulation versus Ex-Post Antitrust

As noted in the introduction, a common theme in many proposals to improve the regulation of competition in the 21st Century highlight the use of what their proponents label ex-ante regulatory regimes.[7]

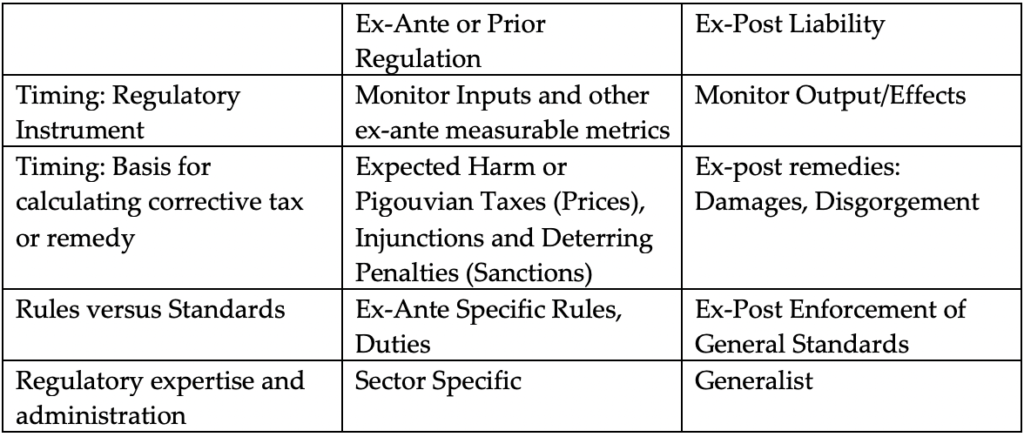

Thus, it is critical, as a preliminary matter, to define the essential features of ex-ante regulation that differentiate this approach from traditional litigation-based antitrust enforcement. Table 1 lists several ways in which ex-ante regulation and ex-post liability approaches might differ. However, as will become clear, many of these identified differences between ex-ante regulation and ex-post litigation are less substantial in practice and of limited use as an organizing principle. As we will demonstrate, antitrust law already incorporates many features of ex-ante regulation.[8] Instead, we find that the best approach to distinguish between antitrust and regulation, following Carlton and Picker (2014), is one that focuses upon substantive differences between antitrust and regulation, as well as the institutional competence of the regulator tasked to administer the regime.

Table 1

A natural starting point for many analyses of the difference between ex-ante regulation and ex-post liability is timing. Ex-ante regulation attempts to impose its corrective incentives on the activity of economic actors before or at the same time it occurs. As a result, the two approaches differ in both the instrument and remedy used to generate incentives. Ex-ante regulation approaches focus on input levels[9] and other ex-ante measurable metrics to impose incentives (e.g., Pigouvian taxes) or to directly regulate activity levels.[10] In contrast, litigation-based liability systems focus on outputs or outcomes and use harm-based damages to shape incentives that alter the firm’s behavior or activity level. In a frictionless world void of transactions and information costs, these two systems are capable of generating identical incentives.[11] However, in real economies with positive transactions and information costs, the performance of the two systems will differ. Because ex-post liability systems evaluate the activities of firms later in time after information on the effects of an activity has been revealed, the information advantage favors the use of ex-post liability systems when there is heterogeneity that is known to the regulated firms (but not the regulator) ex-ante. But this advantage may not be important when such heterogeneity is minimal or when it cannot be predicted ex-ante by the regulated firms.[12] Moreover, the absence of effective ex-post remedies may favor the ex-ante approach even with heterogeneity.[13]

While this literature successfully identifies reasons for the use and timing of particular regulatory instruments, it is less clear that it usefully distinguishes between antitrust and many proposals for the ex-ante regulation of competition. Under this definition based upon timing and regulatory instruments, there are prominent examples of ex-ante regulation of competition within antitrust law. Consider the requirements for premerger notification under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act (HSR Act) in the U.S.,[14] and similar requirements in other jurisdictions around the world.[15] Under the HSR Act, parties in covered transactions must notify the U.S. antitrust agencies of the proposed transactions, file certain information, and wait a specified time period before consummating certain mergers or acquisitions.[16] Prior to the enactment of the HSR act, many challenges to mergers occurred after the merger had been consummated. Agencies often lacked the evidence to prove that a transaction would lessen competition prior to the consummation of the merger, making it difficult to obtaining preliminary injunctions to prevent the parties from merging.[17] While challenges to consummated mergers may allow for the direct observation of the anticompetitive effects of the merger and mitigate the agencies’ information disadvantages,[18] the antitrust authorities were frequently unable to restore competition lost to a consummated anticompetitive merger due to the inability to secure timely and effective remedial relief.[19]

The premerger notification program under the HSR Act addressed the weaknesses of merger control based on ex-post litigation by facilitating ex-ante evaluation and regulation of certain mergers and acquisitions. First, the HSR Act narrows the information gap that would otherwise exist between pre- and post-merger evaluations of the effects of a merger. The Act requires that information be filed along with the initial HSR notification and allows the agencies to request additional information and documentary materials when they determine further inquiry is required. This facilitates a more informed ex-ante evaluation of the proposed transaction and allows the agencies to more accurately distinguish between anticompetitive transactions and those that are procompetitive or benign. Second, the waiting period and notification requirements allow the antitrust agencies to evaluate mergers before they are consummated. This allows the government to obtain preliminary injunctions to prevent consummation of the merger and facilitates the use of ex-ante structural remedies. The ability to obtain ex-ante remedies reduces the problems caused by the agencies’ inability to restore competition after the consummation of anticompetitive mergers due to the lack of effective ex-post remedies.[20]

The second factor listed in Table 1 used to distinguish ex-ante and ex-post approaches is a “rules versus standards” distinction.[21] The standard analysis of ex-ante rules versus ex-post standards incorporates the timing tradeoffs discussed above—optimal ex-ante rules often require a more complete ex-ante determination of the specific contours of the rule and the consequences of violating the rule, while ex-post standards and the remedy to be applied are given specific content only after an individual or firm acts and relevant information is revealed.[22] As noted above, which of these approaches generates higher social welfare in a particular setting will depend upon information costs—including the government’s cost of acquiring and disseminating information about the applicable rule or standard to the public, and the costs of discerning whether not an individual or firm has violated the rule or standard. Moreover, these costs can change over time. For example, in dynamic industries, rapid innovation can make carefully crafted rules obsolete. In contrast, ex-post adjudications under a standard can evolve to changes and are less prone to obsolescence.[23]

There is a second important dimension to the rules versus standards distinction relating to the optimal level of complexity and detail contained in the two approaches. In many analyses, this dimension is suppressed by the assumption that the relevant analysis is between simple bright line rules and more complex standards. Indeed, many of the proposals to replace “ex-post” litigation based antitrust are calls to establish lists of prohibited practices (blacklists) for certain firms (e.g., firms that meet a structural presumption or are identified as a gatekeeper).[24] Such bright line rules establishing conduct as illegal per se would replace complex and costly determinations of liability based upon evidence of a business practice’s anticompetitive effects.

But these proposals do not go outside the current or historical bounds of the antitrust laws and do not provide a useful basis for distinguishing between antitrust and regulation. The antitrust laws already recognize practices as being so inherently and commonly unreasonable that courts might dispense with an elaborate analysis and condemn them as illegal per se. Thus, the identification of such practices, including the identification of new practices based on strong theoretical and empirical evidence, would be consistent with the historical operation of the antitrust laws and easily accommodated by the current evidence-based system of antitrust laws. The Court has also maintained and developed truncated forms of analysis under the rule of reason, recognizing that not all antitrust inquires required the same degree of fact-gathering and analysis.[25] Such an approach is broadly consistent with an economic approach to the design of the antitrust laws that seeks to balance the costs of errors and the costs of administration.[26]

In contrast, the outright condemnation or blacklisting of practices or behaviors without such evidence would not rest easily with the current evidence-based system of antitrust laws.[27] Rather, the latter approach would be consistent with the abandoned approach taken during the early history of the U.S. antitrust laws, where the per se categorization was used extensively to condemn many procompetitive practices. In contrast, much of the recent evolution of the U.S. antitrust laws involved replacing existing and unsupported presumptions and per se rules with a rule of reason analysis that evaluates the impact of a challenged behavior on competition.[28]

Consider, for example, the recent proposal to prevent platform firms from selling their own products if they compete with offerings from non-vertically integrated sellers.[29] But economic evidence from forced vertical disintegration in other industries shows that similar proposals to force vertical disintegration to protect competitors reduce consumer welfare. For example, evidence from state laws that prevented gasoline refiners from operating retail gas stations found that these laws raised prices and lowered the quality of retail gasoline services in these states relative to states that allowed the use of vertical integration.[30] Moreover, recent evidence from the recent voluntary exit of refiners from gasoline retailing also show the opposing unilateral price effects involved in vertical integration and de-integration consistent with the approach contained in the 2020 U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission Vertical Merger Guidelines.[31]

In the more general case, the simple rules versus complex standards dichotomy may not usefully differentiate between ex-ante regulation and ex-post liability either. Rules can be complex, and standards can be enforced using simple rules. The evolution of merger enforcement illustrates both of these points. The principal U.S. antitrust law governing mergers and acquisitions, Section 7 of the Clayton Act, sets out a broad standard for the evaluation of mergers, prohibiting mergers and acquisitions “where, in any line of commerce or in any activity affecting commerce in any section of the country, the effect . . . may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.”[32]

However, at times, both the Court’s precedents and the Merger Guidelines promulgated by the federal antitrust agencies reflected the use of relatively simple rules based upon market concentration to guide merger enforcement. Under the Court’s existing precedent in Philadelphia National Bank (PNB), the plaintiff makes its prima facie case by showing that the proposed transaction would result in the merged firm controlling 30 percent of the market involved in the merger or acquisition. When the Court’s PNB structural presumption applies, it makes evaluation of a merger under Section 7 of the Clayton act simpler, with the Court noting that:

This intense congressional concern with the trend toward concentration warrants dispensing, in certain cases, with elaborate proof of market structure, market behavior, or probable anticompetitive effects. Specifically, we think that a merger which produces a firm controlling an undue percentage share of the relevant market, and results in a significant increase in the concentration of firms in that market is so inherently likely to lessen competition substantially that it must be enjoined in the absence of evidence clearly showing that the merger is not likely to have such anticompetitive effects.[33]

The problem with the PNB Court’s structural approach is that market structure is not a reliable starting point for the analysis of a merger’s effect on competition and thus is unlikely to effectuate the goals of the standard set out in Section 7 of the Clayton Act.[34] And while the Court has replaced similar misguided per se rules under Section 2 of the Sherman Act with the rule of reason over the same time period,[35] the Court’s misguided PNB structural presumption is still good law due to the Court’s decades-long hiatus from merger law.[36]

In contrast, the evolution of merger enforcement at the agencies over the past half century illustrates the evolution toward the use of effects-based tools that attempt to effectuate the Section 7 standard. In particular, the HSR Act’s premerger notification requirements discussed above, together with the regularized practice of evaluating a large volume of merger transactions each year generated a constant demand at the agencies for resources and tools to evaluate proposed transactions. The existence of hundreds of lawyers and economists in two federal agencies whose primary duties are to evaluate proposed transactions in a short time period likely contributed to the evolution of the agencies’ approach to merger enforcement, both in practice and in written guidelines. While the U.S. Department of Justice’s initial 1968 Merger guidelines, like the Court, incorporated the idea that horizontal mergers that increased market concentration were “inherently likely to lessen competition,”[37] the antitrust agencies have largely moved beyond relying on market structure as the principal guide to enforcement both in practice and in later versions of the Horizontal Merger Guidelines. In particular, the 2010 Horizontal Merger guidelines deemphasize the use of simple proxies such as measures of concentration in favor of more sophisticated models to predict merger effects.[38]

The evolution of the merger guidelines highlights the importance of institutional competence and fit in determining both the bounds of a regulatory approach as well as the allocation of tasks between approaches. Indeed, these institutional structures have been used to explain features of ex-ante sector regulation that are not commonly found in the antitrust laws. In particular, the antitrust laws are based on generally applicable standards (e.g., to insure the proper functioning of markets in order to protect the competitive process and maximize consumer welfare).[39] Because the common law of antitrust is produced by generalist judges with limited specific industry knowledge and expertise, they are ill suited to effectively supervise and administer price regulations, especially in dynamic industries.[40] In light of this, the antitrust laws in the U.S., with a few notable exceptions,[41] have maintained a strict separation between antitrust law and price regulation.[42] A corollary of this separation is a cautious and limited approach to antitrust duties to deal, which would require a specification of the price at which the involuntary transaction would take place.[43]

Because detailed and specific knowledge is required to engage in price setting through regulation, such tasks are generally allocated to specialist sector regulators administering sector specific regulations.[44] The historical use of sector regulation and sector regulators to administer price setting and duties to deal is consistent with an ex-ante choice of regulation over antitrust based on comparative advantage.[45] Because of this focus, regulatory regimes have often focused on network industries that exhibit economies of scale and issues relating to access rights and interconnection duties. While such sector specific regulatory regimes may be better suited to regulating price and interconnection duties in theory, in practice these regimes are imperfectly carried out and have often proven to be costly and ineffective. The use of industry specific regulators can result in the regulators being captured by the agencies,[46] and legislation to enact a regulatory regime often reflects the preferences of those being regulated rather than an attempt to maximize consumer welfare.[47] The result of ineffective sector regulation has often been deregulation,[48] and a return to the market and the protection of the competitive process through antitrust law.[49]

II. Antitrust or Regulation and the Doctrine of Implied Immunity

The choice to use sector regulation to control competition can generate conflicts between what is lawful under the regulatory statute and what is lawful under the antitrust laws. Litigation over conflicts between the antitrust laws and sector regulations began almost immediately after the passage of the Sherman Act in 1890.[50] In theory, both the legislative body that passes the law and the courts that enforce the laws can attempt to clarify what law applies to the conduct. For example, Congress can pass specific immunity from the antitrust laws[51] or include antitrust savings clauses in regulatory statutes that specifically set out the ability of antitrust to reach regulated conduct.[52] Specific immunity from the antitrust laws is costly and generally disfavored, and courts have found savings clauses “unhelpful.”[53] Historically, implied repeals of the antitrust laws due to the presence of an overlapping regulatory statute were “strongly disfavored.”[54] Over time, however, the limits on the operation of the antitrust laws in the presence of regulation has been expanded to the point where the Court has created broad limits on the application the federal antitrust laws in the presence of existing sector regulation, both in the presence and in the absence of antitrust saving clauses. As a result, the choice to use sector regulation to control competition can also be a choice to displace the antitrust laws and treat antitrust and regulation as substitutes.[55]

The Court set out its approach to conflicts between antitrust and regulation in the presence of an antitrust savings clause in Verizon v. Trinko.[56] In that case, Trinko, a local exchange customer of AT&T, filed a class action lawsuit against Verizon claiming that its anticompetitive refusal to deal with AT&T on terms required by the Telecommunications Act of 1996 (1996 Act) violated Section 2 of the Sherman Act.[57] In particular, the 1996 Act required specific interconnection duties at reasonable and non-discriminatory prices and provided for the regulatory enforcement of these duties. Verizon had failed to comply with the regulatory duties to interconnect, and agreed to a consent decree that required it to pay $3 million to the United States. Verizon also agreed to pay $10 million to AT&T and other local exchange carriers harmed by Verizon’s failure to comply with the 96 Act’s interconnection requirements. In the class action, filed the day after the FCC issued the consent decree, plaintiff Trinko attempted to turn Verizon’s failure to comply with the 1996 Act’s regulatory duty to deal (RDTD) into a violation of §2 of the Sherman Act. The Court disagreed, finding that the 1996 Act’s RDTD was distinct from antitrust duties to deal, and holding that Trinko’s complaint alleging breach of a RDTD does not state a claim under §2 of the Sherman Act.[58]

Because the 1996 Act also included a specific antitrust savings clause, the Court could not base its decision to grant Verizon’s motion to dismiss on a finding of implied immunity.[59] In interpreting the effect of the antitrust savings clause, the Court noted that “just as the 1996 Act preserves claims that satisfy existing antitrust standards, it does not create new claims that go beyond existing antitrust standards; that would be equally inconsistent with the saving clause’s mandate that nothing in the Act ‘modify, impair, or supersede the applicability’ of the antitrust laws.”[60] As a result, the 1996 Act’s extensive RDTD did not create or impose an equivalent antitrust duty to deal (ADTD). The Court then turned to the question of whether Verizon’s failure to comply with the 1996 Act’s RDTD violated pre-existing antitrust standards. The Court held that it did not, finding that the ADTD under existing antitrust standards (with the Court’s decision in Aspen Skiing “at or near the outer bounds of §2 liability”) was limited[61] and not violated by Verizon’s conduct.[62]

As others have noted, “the significance of [Trinko] is not that the Court reached that result in this particular case, but in the broad reasoning through which it did so.”[63] A narrow decision finding that a complaint that merely pleads a violation of a RDTD is insufficient to state a claim under §2 would not be particularly noteworthy or controversial.[64] Indeed, rejection of the Second Circuit’s adoption of a very liberal pleading standard under the existing “no set of facts” standard from Conley v. Gibson may have surprised some at the time Trinko was decided.[65] But the novelty of such an approach would certainly be diminished by the Court’s 2007 decision in Twombly,[66] which replaced the liberal “no set of facts” pleading standard with a plausibility standard that invites a relative comparison that examines whether the plaintiff’s hypothesis is “not merely parallel conduct that could just as well be independent action.”[67] Moreover, a decision that simply held that the petitioner’s violation of the extensive RDTD does not violate the antitrust laws under the Court’s existing duty to deal precedents would not be particularly controversial either. Even a well pled complaint alleging a violation of §2 based on a refusal to deal would bear a heavy burden to prove liability under the Courts current precedents.[68] Again, the surprise generated by such a holding would have been the timing of the ruling (at the motion to dismiss stage rather than at summary judgment) and not the finding that the plaintiff’s claims were weak. Some argue that the Court’s description of the current limits of the ADTD under current precedent was inaccurate and significantly narrowed the circumstances where an ADTD exists,[69] but even a decision that included a narrowing of the ADTD would have few if any implications for the limits on the operation of the antitrust laws in the presence of sector regulations.

The implications for the limits on antitrust in the presence of sector regulation from the Court’s Trinko decision come from the Court’s use of an analysis that would examine the marginal net benefits of applying antitrust law in the presence of regulation. The Court noted that “just as regulatory context may in other cases serve as a basis for implied immunity, it may also be a consideration in deciding whether to recognize an expansion of the contours of § 2.”[70] The Court then applied an error cost analysis of the marginal net benefits of applying antitrust law given the existence of the 96 Act,[71] and found that the existence of the extensive RDTD diminished the marginal effect of antitrust enforcement.[72] Thus, while not an implied immunity case, the Court’s use of a marginal cost benefit test diminishes the reach of the antitrust laws in the presence of overlapping sector regulation, and conditions the reach of the antitrust laws on the degree to which such overlapping regulations control competition.[73]

The Court’s Trinko decision also affected the relationship between regulation and antitrust by providing a model for the expansion of the implied immunity doctrine, which governs the ability of antitrust law to reach conduct subject to federal regulation in the absence of an antitrust savings clause.[74] The Court’s most recent antitrust implied immunity holding came in Credit Suisse v. Billing,[75] decided three years after Trinko. In Credit Suisse, the Court dismissed a variety of class action antitrust claims brought by investors against investment banks that had formed underwriting syndicates used to sell securities in connection with an initial public offering (IPO).[76] The Supreme Court, in a 7-1 decision held that the antitrust claims against the investment banks were impliedly preempted under a “clear incompatibility” standard.[77] The influence of the Court’s approach in Trinko is apparent, as it adopted an approach to clear incompatibility based on a cost-benefit analysis that focused on the marginal benefit of antitrust enforcement in the presence of sector regulation.[78] The Court relied on a number of factors to find that the marginal benefit of applying antitrust did not outweigh its costs in this setting, observing that intricate securities-related standards separate encouraged from outlawed behaviors, that securities-related expertise is needed to properly decide such cases, that “reasonable but contradictory inferences” may be reached from the same or overlapping evidence, and that there is a substantial risk of inconsistent court results. The Court then concluded that “these factors suggest that antitrust courts are likely to make unusually serious mistakes.”[79]

Some have noted that the Court’s marginal benefit analysis in Credit Suisse potentially expands the application of implied immunity beyond the bounds set in the Court’s previous implied immunity decisions.[80] The Court’s prior holdings imply that antitrust law is plainly repugnant if it can disallow conduct that the regulator could authorize under the statute.[81] These decisions were broad in the sense that they required only the potential for a conflict, and did not require that the antitrust laws conflict with actual implementation of the regulatory statute.[82] But the Court’s decisions before Credit Suisse also narrowed the applicability of the doctrine and facilitated the use of the antitrust laws as a complement to regulation. Implied immunity would not apply to complementary or overlapping antitrust actions challenging anticompetitive conduct that could not be authorized under the statute.[83] Nor would it apply to duplicative antitrust actions challenging anticompetitive conduct that is also illegal under the regulatory statute.[84]

Although the Court’s Credit Suisse decision did not overrule its earlier precedents in this area, it expanded the implied immunity doctrine beyond its previous boundaries by applying it to a case of overlapping laws, where challenged conduct (in this case, the tying claim) would be a potential violation of both the antitrust and securities laws.[85] Indeed, the case where the enforcement of antitrust law duplicates the enforcement of securities law would present a clear case where the marginal benefit of applying antitrust is low. In such a case, any cognizable costs of erroneous antitrust decisions could easily outweigh these low marginal benefits. In addition, even if overlapping enforcement does not produce conflicting outcomes on liability, it can, without explicit coordination between the laws and agencies, result in over deterring remedies.[86]

Setting aside the merits of the Court’s holdings, it is clear that Trinko and Credit Suisse advance a “broad regulatory displacement standard for federal antitrust claims in fields subject to regulation.”[87] A primary implication of this broad approach to regulatory displacement of antitrust is that the ex-ante decision to allocate control of competition to sector regulation will take on even more importance, as such a choice can be a choice to disable antitrust and its potential function as a complement to fill gaps left by regulation.[88] Moreover, the Court’s marginal analyses in Trinko and Credit Suisse focus on low benefits and error costs generated by enforcing the antitrust laws, but take the presence of sector regulation as given. But the ex-ante choice between antitrust and regulation begins with a different perspective in which the potentially significant imperfections and error costs of both regulation and antitrust are taken into account. In particular, such an approach would ensure that great care be exercised in ensuring that the use of ex-ante regulation is limited to those areas in which such an approach possesses a comparative advantage.

III. Antitrust and Sector Regulation for Pharmaceutical Innovation: Hatch Waxman and State Drug Substitution Laws

In this section, we examine the use of antitrust in the presence of sector regulation for pharmaceutical innovation—the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984,[89] (aka Hatch-Waxman Act) and related State Generic Substitution Laws. The Hatch-Waxman (HW) Act provided a specific solution to the use-creation tradeoff that is at the core of the economic analysis of innovation.[90] Together, the HW Act and state GSL regulations form a comprehensive system of ex-ante regulations that alter both static and dynamic competition in markets for prescription drugs.

The HW Act contains regulations that alter post-patent competition in affected markets aimed at lowering prices of off patent drugs faster and reducing use costs.[91] The HW Act lowered the cost of generic entry by allowing generics to use an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). An ANDA is approved if the generic demonstrates that its generic drug is bioequivalent to a reference listed drug (RLD). RLDs are listed in an FDA publication known as the “Orange Book”, which identifies FDA approved drug products and related patent and exclusivity information.[92] Because the ANDA does not require that the potential generic entrant produce evidence from clinical trials that their drug was safe and effective, the ANDA process costs a fraction of what is required to obtain marketing approval for the RLD through a New Drug Application (NDA).[93] ANDA Filings under Paragraph I-III of the HW act were designed to speed generic entry after the expiration of the patent and quickly lower the prices of off patent drugs.[94] Not only do they lower the regulatory costs of obtaining FDA marketing approval for generic entrants, but under HW, ANDA applicants do not have to wait for the patents to expire to begin using samples of the RLD to achieve and demonstrate bioequivalence and to prepare its ANDA.[95]

In addition, the HW act sought to alter competition prior to the expiration of patents covering a drug though incentives for firms to challenge patents. This is accomplished through the use of a 180-day marketing exclusivity period for the first generic firm to file a substantially complete ANDA with Paragraph IV certification, which certifies that the listed patents protecting the RLD are either invalid or not infringed. The filing of a Paragraph IV ANDA creates an act of infringement that allows the patentee to file an infringement suit. The filing of a lawsuit triggers a thirty-month stay on FDA approval of the ANDA and allows time for the parties to litigate the challenge to the patent.

Finally, competition in drug markets is regulated by state generic substitution laws. Since the early 1970s, all states allow pharmacists to substitute generic drugs when the prescription is written for the brand name drug.[96] Some state laws are permissive, while other states’ laws mandate substitution.[97] States’ laws also differ on whether the consent of the patient is presumed or required,[98] and the circumstances under which a drug must be substituted.[99] While the HW act facilitates free riding on the RLD’s data on safety and efficacy generated during clinical trials, these state laws seek to further increase the penetration of generic drugs by allowing generics to free ride on the brand’s expenditures on promoting the RLD to doctors, payers, and patients.

Because the HW Act and state GSL regulations alter post-patent competition in a way that lowers off patent drug prices more quickly and more often, these regulations that serve to lower the lifetime use costs associated with patented drugs will also lower the anticipated returns to a patent on the margin, and will have a negative effect on the incentive to innovate.[100] Moreover, successful Paragraph IV challenges that invalidate patents and the generation of higher costs involved in defending valid patents from Paragraph IV challenges also reduce anticipated returns to patents. To offset these effects, the HW Act sought to maintain or improve incentives to innovate through restoring a part of the patent term taken up during the process of obtaining FDA approval of a NDA[101] and granting five years of exclusivity for clinical trial data generated during this process.[102] There is some evidence that the HW regulations diminished the effective patent life and net returns to pharmaceutical innovation relative to the pre-HW days. For example, a 1996 study found that the effective patent life of a pharmaceutical patent was between fourteen and seventeen years (9 years of effective patent life left after FDA marketing approval plus between five to eight years post expiration before generic entry). After HW, the effective patent life, including patent term restoration, was 11.7 years.[103]

Despite the comprehensive system of regulation of both static and dynamic competition contained in the HW Act, the antitrust laws have been allowed to operate in a complementary way in these markets. Until 2003, the HW Act did not have an antitrust savings clause, and the specific savings clause enacted as part of the Medicare Modernization Act was narrow, serving to clarify that the lack of a challenge to a patent settlement by the FTC or DOJ would not act as a bar to any action, and to limit any inference or presumption resulting from agency action.[104] The scope for implied preemption of the antitrust laws was also narrowed by the fact that the specific regulations with respect to patent law issues and marketing exclusivity were not carried over to issues that became the focus of antitrust actions. These include the settlement of patent litigation, product improvements, and duties of firms selling branded drugs to deal with generic firms. Because the HW regulations were silent with respect to these issues, antitrust was available to fill these gaps in the regulation when the incentives of firms generated outcomes that were not consistent with the intended goals of the HW legislation.[105] On the other hand, a significant question exists as to whether antitrust or regulation is the right tool to address these issues. For the reasons stated elsewhere in this chapter, antitrust has proven to be an awkward and ineffective tool. We suggest that regulatory reform, rather than antitrust, may be a better approach to filling gaps in the HW regulatory scheme.

In the remainder of this section, we examine the areas of antitrust litigation mentioned above and focus on how these issues are generated by the regulatory incentives generated by the HW Act or state GSL laws. We also consider the relative effectiveness of antitrust and potential regulatory solutions. As mentioned above, these focus areas include antitrust litigation challenging patent settlements between branded and generic firms that have filed Paragraph IV ANDAs, brand investments in product improvements that result in prescriptions that are not eligible for substitution under various state GSL laws, and various refusals to deal and foreclosure related antitrust claims.

Perhaps the most prominent area of HW related antitrust litigation is over patent settlements that include payments from the brand name drug companies to generic firms that filed Paragraph IV ANDAs. In these cases, the ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification challenges the validity of the listed patents protecting the drug and creates an artificial act of infringement that allows the branded firm to file a patent infringement lawsuit, which triggers a 30 month stay of FDA action on the ANDA. The antitrust inquiry in these cases focuses on the settlement agreements used to end the patent litigation, and in particular the use of monetary payments in the settlements (branded “reverse settlements” because the payments flow from the plaintiff (the branded firm) to the defendant (the generic firm)).[106]

At the outset, we note that consideration flowing from the plaintiff to the defendant in these cases is not only unsurprising, but necessary to settle such cases. Without the regulatory superstructure and the creation of an “artificial” act of infringement, HW Paragraph IV, zero damage infringement cases are in effect actions by the generic firm to declare the patent invalid. In the absence of damages from infringement, monetary settlement of a declaratory judgment action would involve “forward” or “normal” payments from the branded defendant to the generic plaintiff. The “reverse” nature of the payments only occurs because of the way the HW regulations create an artificial act of infringement. Moreover, cases involving patentee filed infringement cases with damages that settle for a discount relative to expected damages would include an implied “reverse” payment from the plaintiff to the defendant. Thus, there is nothing odd or noteworthy about the “reverse” nature of the payments.

The payments are objectionable, from a static consumer welfare standpoint, because they result in settlement agreements that delay the entry of the generic firm more than settlements that do not involve any monetary payment from the branded firm to the generic entrant.[107] After more than a decade of litigation over whether and when these “reverse settlements” violated the antitrust laws, the Court in FTC v. Actavis rejected bright line rules of legality and illegality in favor of a standard to be fleshed out by the lower courts applying the rule of reason.[108] At the same time, the Court recognized the costs of an unconstrained rule of reason analysis and suggested a simpler rule—an inference based on the “reverse payment” exceeding the plaintiff’s litigation costs.[109] The avoidance of litigation costs is a traditional reason for settlement, both in economic models and actual litigation.[110] However, it is far from clear that the Court’s Actavis inference provides useful guidance in separating between pro and anticompetitive settlements given that the antitrust focus in these cases is solely upon static competition, and does not consider the dynamic effect of these cases on innovation or the balancing of use and creation that was central to the HW regulatory scheme.[111]

Moreover, an antitrust focus on the terms of patent settlements misses the point from the standpoint of the regulatory goals of the HW Act if this focus does not materially affect the parties’ decision to settle rather than litigate. Indeed, a primary regulatory goal of HW Paragraph IV certifications is to induce the production of a public good—the invalidation through patent litigation of “bad” patents—a goal that can only be achieved through litigation to judgment.[112] Our earlier analysis shows that even with the Court’s “Actavis inference” as a constraint on the size of any reverse payment, there is a very strong incentive to settle rather than litigate as the elimination of the risk of early prepatent generic competition preserves the patentee’s rents whether the underlying patent is valid or not.[113] For “bad” patents, settlement is inconsistent with the goal of inducing generic litigants to provide the public good of litigation to judgment and invalidating the patent. Moreover, since application of the Actavis inference does not contemplate an inquiry into the validity of the patent, there is a significant risk that firms with branded drugs will be forced to allow early generic entry despite having strong patents. For valid patents, this generates higher type I error costs by inducing settlements that are more costly to the firm selling the RLD protected by valid patents.

One alternative to the decades long and ineffective antitrust litigation would be to address the regulatory incentives HW ANDA Paragraph IV applicants have to litigate patents through regulatory reform and not antitrust. Indeed, some have argued that the most promising path towards improving incentives to litigate and invalidate bad patents is through regulatory reform that makes a Paragraph IV ANDA applicant eligible for the 180-day marketing exclusivity only if it successfully invalidates the patent.[114] Ironically, the FDA, through their successful defense requirement, imposed such a requirement early on. However, this FDA requirement was struck down by the DC Circuit as inconsistent with the plain meaning of the statute.[115] A simple solution might have been to amend the statute. But this was not done. While marketing exclusivity forfeiture provisions were enacted as part of the 2003 MMA amendments, they did not include settlement as an unconditional reason for forfeiture.[116] Rather than provide a regulatory solution to the problem, the MMA amendments rely on antitrust to operate by providing for forfeiture only if “The first applicant enters into an agreement with another ANDA applicant, the NDA holder, or the patent owner, and there is a final decision of the Federal Trade Commission or an appeals court ‘that the agreement has violated the antitrust laws.’”[117]

Another focus of antitrust litigation surrounding the HW Act involves sample availability, exclusion, and an antitrust duty of the firm with a RLD to deal with prospective ANDA filers. The promotion of generic competition under the HW regulations requires those planning to file an ANDA to have access to samples of the brand’s RLD for purposes of demonstrating bioequivalence. Thus, the HW regulatory design, like the regulatory scheme of the 1996 Telecommunications Act discussed above, requires a duty to deal, as the HW regulations depend on the manufacturer of the RLD’s willingness to make samples of the RLD available to ANDA filers.

However, until recently, the HW regulatory scheme did not contain a regulatory duty to deal. This is in contrast to regulations like the 1996 Telecommunications Act, which required interconnection with specific regulatory duties and enforcement. In the absence of a regulatory duty to deal, firms selling RLDs used a variety of practices that limited the availability of RLD samples to generic firms contemplating an ANDA filing. For example, since 2007, the FDA has the authority to require firms selling RLDs with dangerous characteristics to use restricted distribution systems as part of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program.[118] Firms then used these restricted distribution systems and associated ETASU programs to limit the ability of generic drug manufacturers to obtain sufficient samples of REMS-restricted drugs required to conduct bioequivalence testing for an ANDA.[119]

Numerous generic firms filed private antitrust claims based on the branded firms’ use of REMS restricted distribution systems to prevent generic firms from obtaining samples of the RLD.[120] While the HW Act’s regulatory silence allowed the use of antitrust to police these refusals to deal, such claims based on an ADTD, especially after Trinko, can be challenging, risky, and time consuming. Moreover, as noted above, the limited nature of the ADTD can be explained as a rational response to antitrust law’s shortcomings as a framework for price regulation and duties to deal which require pricing the access. Thus, regulatory control of competition which requires interconnection or similar duties to deal should, as a matter of ex-ante design, include such duties as part of the regulation.

While no such provision was included in the HW regulatory scheme originally, a regulatory duty to deal was passed and signed into law in December of 2019.[121] In particular, this RDTD requires the branded firm to provide in a timely manner a sufficient quantity of the RLD at commercially reasonable, market based terms.[122] The legislation also allows the generic firm to obtain a REMS covered product authorization to obtain sufficient quantities from the Secretary of Health and Human Services. A failure to comply with the RDTD allows the generic firm to bring a civil action. Remedies include reasonable attorney’s fees and costs of the civil action, and deterring penalties if the defendant in the action did not have a legitimate business justification for the RTD, or if the defendant failed to comply with an order to provide sufficient quantities of the RLD under the Act. The inclusion of a RDTD in the HW regulatory design twenty-five years after the passage of the HW Act illustrates the use of a regulatory solution to a regulatory problem, and an appropriate (but not quick) resolution of the allocation of tasks between antitrust and regulation. Prospectively, this RDTD should mitigate the demand for generic firms to bring ADTD cases, and under Trinko, result in regulatory displacement of such claims.[123]

A third set of antitrust cases generated by regulatory incentives involve the state GSLs and the use of strategic product reformulations. As noted above, the state GSLs piggyback on the HW scheme by allowing and in some cases mandating that the pharmacy substitute cheaper generic drugs when the prescription is written for the more expensive branded RLD. While the HW regulations are built around free riding on the RLD firms’ investments leading up to and during the NDA approval process, the state GSLs are built around free riding on the RLD firms’ investments in advertising, marketing, and selling the RLD.[124]

In particular, while HW promotes free riding on investments that are sunk at the time of generic entry, the operation and effect of the state GSLs depend parasitically on the continued maintenance of the flow of prescriptions for the off patent RLD from doctors. A primary economic effect of the GSLs is the drastic reduction or elimination of firms’ incentives to engage in any advertising or promotion of RLDs subject these laws. For example, in the case of states whose GSLs mandate substitution, a firm that engages in costly promotion that induces a physician to write a prescription for the RLD will have the sale diverted to a lower cost generic.

It will also generate incentives to create and switch promotion to substitute products not eligible for substitution under the state GSL. Indeed, firms facing generic substitution for their RLD have acted on these incentives. In particular, these firms have responded by introducing and promoting new substitute products and either withdrawing or otherwise deemphasizing marketing and sales for the old RLD that would be subject to the GSL laws.[125] These product replacements can involve switching patients to a new patented drug that is therapeutically superior to the soon to be off-patent RLD. However, because the vast majority of the state GSL laws base eligibility for substitution on the generic drug being AB rated, even minor reformulations such as changes in dosage or form (e.g., switching from a tablet to a capsule) can preclude generic substitution under these laws.[126]

Firms’ efforts to engage in product substitution has generated antitrust scrutiny. Plaintiffs have challenged GSL defeating product substitution under an anticompetitive product hopping theory.[127] In these cases, an anticompetitive product hop consists of two elements, a product reformulation, and promotion or detailing aimed at switching prescriptions from the GSL eligible RLD.

Clearly, neither element of a product hopping case alone would generally raise antitrust concerns or raise a viable claim under pre-existing antitrust standards. In general, conduct aimed at preventing free riding on promotion/detailing, including the introduction of new products and packaging, would be competition on the merits in non-regulatory settings. The use of vertical controls such as exclusive dealing or category management can align incentives between manufacturers and retailers, promote the production of consumer information and valuable retail services, and increase both profits and consumer welfare.[128] And the production of new products can be an important source of economic growth and increase consumer welfare.[129]

The point being here is not whether product hopping cases state a viable claim under the existing antitrust standards—indeed cases filed by private plaintiffs have survived defendants’ motions to dismiss.[130] Rather the point is that the incentives to engage in product replacement are generated by a misguided attempt to impose a system of parasitic competition that seeks to impose a form of static textbook perfect competition that incorporates little or no actual competition and generally does not exist in actual markets.[131] The regulatory scheme in the GSL laws also ignores and indeed devalues dynamic competition. Regulatory schemes that attempt to artificially produce such textbook outcomes will be prone to generating unintended consequences that flow from the actual incentives created by the regulations. Indeed, one consequence of the state GSL laws is to make both the RLD and generic firms unlikely to engage in promotion and detailing because of free riding by other generics. Otherwise, one could rely on promotion by generic firms and not state GSL laws to make cheaper generic drugs available to consumers. If consumer access to cheap and effective generic treatments is generated, as some have suggested, by promotion induced agency costs on the part of doctors, insurers, or pharmacy benefit managers, then any regulatory solution should focus on attempting to address these agency costs, rather than creating an artificial parasitic form of competition that makes the production of information by all of the sellers in the market unprofitable.

Moreover, trying to use antitrust as a gap filler to respond to the regulatory incentives created may generate more costs that benefits. Indeed, as Carlton et al. (2016) point out, cases based on a product hopping theory are “at best a misguided attempt to use antitrust law to fix a regulatory problem . . . . Using antitrust law to fix such a regulatory problem . . . would not only potentially cause consumer harm in pharmaceutical markets, but also create an undesirable antitrust precedent for other industries.”[132] This is because, as noted above, the structure of antitrust law makes it a poor vehicle for addressing the particular regulatory problems created in product hopping cases. For starters, an antitrust claim under a product hopping theory would also require an antitrust evaluation that would have to undertake the difficult task of weighing any benefit from product innovation against any antitrust harm, a task that generalist antitrust courts would also be ill suited to undertake.[133] In addition, these claims would also require the creation of an antitrust duty for the branded company to continue selling what it views as an obsolete drug in order to allow its generic competitors to take advantage of GSLs.[134] Moreover, no such duty exists under existing antitrust standards, and under Trinko and NYNEX, regulatory obligations or the evasion of regulatory obligations, without more, do not create antitrust violations.[135]

Conclusion

Using ex-ante regulation to replace inefficient and ineffective ex-post litigation based antitrust is a familiar refrain for those interested in regulating large technology firms. But the narrative that antitrust is either solely or predominantly based on ex-post litigation is a false narrative, as both the current antitrust laws and its institutions incorporate many of the features that reformers put forth as ex-ante regulation. As a matter of optimal regulatory design, this is not surprising, as a true ex-ante approach will incorporate both approaches.

In the U.S., the Supreme Court has expanded its implied immunity and related common law limits on the use of the antitrust laws in response to the potential costs of inconsistent and overlapping regulation. This forces an ex-ante choice between antitrust and sector specific regulation when addressing specific problems associated with regulated industries. We suggest the ex-ante choice between antitrust and sector regulation be made based on the comparative institutional advantage of each approach, and that such an approach will result in the allocation of duties to deal and price setting to sector specific regulators. Because both approaches are imperfect vehicles for controlling competition, both the initial allocation between antitrust and regulation and the choice to regulate in the first place should be undertaken with caution, and expected to involve a long, slow, and costly evolution towards a more efficient system of antitrust and regulation.

Foonotes

[1] For a detailed description of regulatory proposals, see Marco Cappai & Giuseppe Colangelo, Navigating the Platform Age: The “More Regulatory Approach” to Antitrust Law in the EU and the U.S. (Stanford-Vienna Transatlantic Tech. L.F. Working Paper No. 55, 2020), https://www-cdn.law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/cappai_colangelo_wp55.pdf.

[2] Id.; see, e.g., Murat C. Mungan & Joshua D. Wright, Optimal Standards of Proof in Antitrust (July 30, 2019). George Mason L. & Econ. Research Paper No. 19-20, 2019), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3428771 (discussing optimal standards of proof).

[3] See Timothy J. Muris, The Rule of Reason After California Dental, 68 Antitrust L.J. 527, 532–38 (2000).

[4] See Cappai & Colangelo, supra note 1, at 7, 12, 22.

[5] See Dennis W. Carlton & Randall C. Picker, Antitrust and Regulation, in Economic Regulation and its Reform: What Have We Learned? 25, 33 (Nancy L. Rose, ed., 2014), https://www.nber.org/

chapters/c12565.pdf.

[6] Howard A. Shelanski, The Case for Rebalancing Antitrust and Regulation, 109 Mich. L. Rev. 683 (2011); see generally Charles D. Kolstad, Thomas S. Ulen & Gary V. Johnson, Ex Post Liability for Harm vs. Ex Ante Safety Regulation: Substitutes or Complements? 80 Am. Econ. Rev. 888 (1990); Steven Shavell, A Model of the Optimal Use of Liability and Safety Regulation, 15 RAND J. Econ. 271 (1984); see also Kobayashi & Wright, infra note 76.

[7] See, e.g., Eur. Comm’n, Single Market – New Complementary Tool to Strengthen Competition Enforcement, https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12416-New-competition-tool (last visited Oct. 14, 2020); Majority Staff of H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 116th Cong., Investigation of Competition in Digit. Mkts. 386–87 (2020), https://judiciary.house.gov/uploadedfiles/competition_

in_digital_markets.pdf [hereinafter House Majority Report]; Stigler Comm. on Digit. Platforms, Chicago Booth Sch. of Bus., Final Report 32 (2019), https://www.chicagobooth.edu/-/media/research/stigler/pdfs/digital-platforms—committee-report—stigler-center.pdf.

[8] See, e.g., Kevin Coates, Ex-Post and Ex-Ante Rules, 21st Century Competition (Aug. 6, 2020) http://www.twentyfirst centurycompetition.com/2020/08/ex-ante-and-ex-post/ (suggesting that the terms ex-ante regulation and ex-ante competition are frequently used but are “neither accurate nor particularly helpful to the discussion”).

[9] See Donald Wittman, Prior Regulation vs. Post Liability: The Choice Between Input and Output Monitoring, 6 J. Legal Stud. 193 (1977).

[10] See Brian Galle, In Praise of Ex-Ante Regulation, 68 Vand. L. Rev. 1715 (2015).

[11] See id.; see generally Ronald Coase, The Problem of Social Cost, 3 J.L. & Econ. 1 (1960).

[12] Cf. Galle, supra note 10; see generally Louis Kaplow, The Value of Accuracy in Adjudication: An Economic Analysis, 23 J. Leg. Stud. 307 (1994).

[13] See Galle, supra note 10, at 1728–29.

[14] Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976, 15 U.S.C. § 18a (§ 7a of the Clayton Act).

[15] See Int’l Chamber of Comm., ICC Recommendations on Pre-Merger Notification Regimes 1–3 (2015), https://iccwbo.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2017/06/ICC-Recommendations-on-Pre-Merger-Notification-Regimes.pdf (listing the various types of premerger notification regimes worldwide).

[16] See 16 C.F.R. §§ 801–03.

[17] Ronald N. Johnson & Allen M. Parkman, Premerger Notification and the Incentive to Merge and Litigate, 7 J.L. Econ. & Org. 145, 146–48 (1991).

[18] See John M. Yun, Are We Dropping the Crystal Ball? Understanding Nascent & Potential Competition in Antitrust, 104 Marq. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2020), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3698210.

[19] See Kenneth G. Elzinga, The Antitrust Law: Pyrrhic Victories?, 12 J.L. & Econ. 43, 53–66 (1969).

[20] See Johnson & Parkman, supra note 17, at 154–59; see generally Fed. Trade Comm’n, The FTC’s Merger Remedies 2006-2012: A Report of the Bureaus of Competition and Economics 18–20 (2017), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/ftcs-merger-remedies-2006-2012-report-bureaus-competition-economics/p143100_ftc_merger_remedies_2006-2012.pdf.

[21] See generally Louis Kaplow, Rules Versus Standards: An Economic Analysis, 42 Duke L.J. 557 (1992) (“The central factor influencing the desirability of rules and standards is the frequency with which a law will govern conduct.”).

[22] Cf. id. at 568–85 (discussing the tradeoffs associated with ex-ante rules versus ex-post standards).

[23] See Geoffrey Manne, Error Costs in Digital Markets, in The GAI Report on the Digital Economy (2020).

[24] See, e.g., Eur. Comm’n, Single Market Tool, supra note 7; House Majority Report, supra note 7.

[25] See United States v. Addyston Pipe & Steel Co. 175 U.S. 211 (1899); Standard Oil Co. v. United States 221 U.S. 1, 60 (1911); Chicago Board of Trade v. United States 246 U.S. 231, 238 (1918). The Court has also applied a quick look analysis in three cases: FTC v. Indiana Federation of Dentists, 476 U.S. 447 (1986); NCAA v. Board of Regents, 468 U.S. 85, 100-101 (1984); Nat’l Soc’y of Prof’l Eng’rs v. United States, 435 U.S. 679, 692-693 (1978); see also Timothy J. Muris & Brady P.P. Cummins, Tools of Reason: Truncation Through Judicial Experience and Economic Learning, 28 Antitrust, Summer 2014, at 46.

[26] See Manne, supra note 23.

[27] See Cal. Dental Ass’n v. FTC, 526 U.S. 756, 781 (1999) (rejecting the use of quick look analysis, holding: “What is required, rather, is an enquiry meet for the case, looking to the circumstances, details, and logic of a restraint.”); Geoffrey A. Manne, Hal Singer & Joshua D. Wright, Antitrust Out of Focus: The FTC’s Myopic Pursuit of 1-800 Contacts’ Trademark Settlements, Antitrust Source, Apr. 2019, at 1, https://ssrn.com

/abstract=3304769.

[28] See Bruce H. Kobayashi & Timothy J. Muris, Chicago, Post-Chicago, and Beyond: Time to Let Go of the 20th Century, 78 Antitrust L.J. 147, 152–53 (2012) (noting that the incorporation of economics into antitrust law resulted in the Court’s rejection of broad rules of per se illegality); see also State Oil v Kahn, 522 U.S. 3, 21 (1997) (maximum resale price maintenance not per se illegal and subject to the rule of reason, with the Court noting that it has reconsidered its decisions construing the Sherman Act when the theoretical underpinnings of those decisions are called into serious question). See generally Leegin Creative Leather Prods., Inc. v. PSKS, Inc., 551 U.S. 877, 900 (2007) (minimum resale price maintenance subject to the rule of reason); Illinois Tool Works Inc. v. Indep. Ink, Inc., 547 U.S. 28, 42–43 (2006) (no presumption of market power or rule of per se illegality for patent tie-ins); State Oil Co. v. Khan, 522 U.S. 3, 17 (1997) (maximum resale price maintenance subject to the rule of reason); Cont’l T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc., 433 U.S. 36, 58 (1977) (territorial restrictions subject to the rule of reason); Broad. Music, Inc. v. CBS, Inc., 441 U.S. 1, 19–25 (1979) (mandatory license pools subject to the rule of reason); FTC v. Actavis, Inc., 570 U.S. 136, 159 (2013) (patent infringement settlements comprising a “reverse payment” generally subject to the rule of reason).

[29] See, for example, the proposals for forced de-integration of platform firms discussed in Elizabeth Warren, Here’s How We Can Break Up Big Tech, Medium (Mar. 8, 2019) https://medium.com/@teamwarren/heres-how-we-can-break-up-big-tech-9ad9e0da324c; House Majority Report at 377–81.

[30] See John M. Barron & John R. Umbeck, The Effects of Different Contractual Arrangements: The Case of Retail Gasoline Markets, 27 J.L. & Econ. 313 (1984); Michael G. Vita, Regulatory Restrictions on Vertical Integration and Control: The Competitive Impact of Gasoline Divorcement Policies, 18 J. Regul. Econ. 217 (2000); Asher A. Blass & Dennis W. Carlton, The Choice of Organizational Form in Gasoline Retailing and the Cost of Laws That Limit That Choice, 44 J.L. & Econ. 511 (2001) (retail prices increase due to the effect of double marginalization).

[31] Daniel Hosken & Christopher Taylor, Vertical Disintegration: The Effect of Refiner Exit From Gasoline Retailing on Retail Gasoline Pricing (FTC Bureau of Econ. Working Paper No. 344, 2020) (showing that refiner exit from retailing resulted in downward pricing pressure from the reduction in prices to non-integrated retailers, and upward pricing pressure resulting from double marginalization). See generally U.S. Dep’t of Justice & Fed. Trade Comm’n, Vertical Merger Guidelines (2020).

[32] 15 U.S.C. § 18.

[33] United States v. Phila. Nat’l Bank, 374 U.S. 321, 363 (1963); see also Douglas H. Ginsburg & Joshua D. Wright, Philadelphia National Bank: Bad Economics, Bad Law, Good Riddance, 80 Antitrust L.J. 201 (2015).

[34] Ginsburg & Wright, supra note 33, at 204, 207–08 (noting that Philadelphia National Bank‘s adoption of the structure-conduct-performance (SCP) paradigm represents the integration of economic learning into law, but its persistence ignores later theoretical and empirical work in economics exposing the flaws in the SCP approach).

[35] See Kobayashi & Muris, supra note 28, at 152–54.

[36] See Ginsburg & Wright, supra note 33, at 379.

[37] Phila. Nat’l Bank, 374 U.S. at 363.

[38] See, e.g., Carl Shapiro, The 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines: From Hedgehog to Fox in Forty Years, 77 Antitrust L. J. 49 (2010).

[39] Cf. Mission, U.S. Dep’t of Justice Antitrust Div., https://www.justice.gov/atr/mission (last visited Oct. 14, 2020) (“The goal of the antitrust laws is to protect economic freedom and opportunity by promoting free and fair competition in the marketplace . . . [which] benefits American consumers through lower prices, better quality and greater choice.”).

[40] As the Court noted in Trinko: “Allegations of violations of [interconnection] duties are difficult for antitrust courts to evaluate, not only because they are highly technical, but also because they are likely to be extremely numerous, given the incessant, complex, and constantly changing interaction of competitive and incumbent LECs implementing the sharing and interconnection obligations.” Verizon Commc’ns, Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko, LLP, 540 U.S. 398, 414 (2004).

[41] Notable examples are the 1941 antitrust consent decrees between the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI) and the U.S. Department of Justice. The decrees require ASCAP and BMI to issue blanket licenses and provide for a rate court proceeding before the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York when the parties cannot agree on price. For a discussion of the potential costs created by the decrees, see Bruce H. Kobayashi, Opening Pandora’s Box: A Coasian 1937 View of Performance Rights Organizations in 2014, 22 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 925 (2015). The DOJ opened a review of these decrees in 2019. See Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Department of Justice Opens Review of ASCAP and BMI Consent Decrees (June 5, 2019), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/department-justice-opens-review-ascap-and-bmi-consent-decrees; Makan Delrahim, Assistant Att’y Gen., U.S. Dep’t of Justice Antitrust Div., Sign of the Times: Innovation and Competition in Music, Remarks as Prepared for the National Music Publishers Association Annual Meeting (June 13, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/file/1071706/download.

[42] See generally Philip Areeda & Donald F. Turner, Predatory Pricing and Related Practices Under Section 2 of the Sherman Act, 88 Harv. L. Rev. 697 (1975) (setting forth the prevailing test for actionable predatory pricing under Section 2); OECD Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs, Competition Comm. Working Party No. 2 on Competition and Regul., Excessive Prices (Submitted by U.S. Dep’t of Justice and Fed. Trade Comm’n), No. DAF/COMP/WP2/WD(2011)65 (Oct. 2011), https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/attachments/

us-submissions-oecd-2010-present-other-international-competition-fora/1110excessivepricesus.pdf.

[43] See Carlton & Picker, supra note 5, at 26 (“[A]ntitrust is a poor framework for price setting or for establishing affirmative duties toward rivals.”).

[44] See generally id. Examples include the Interstate Commerce Commission (regulating the operation of interstate railroads and limiting rates to those that were “reasonable and just”), the Federal Communications Commission, the Federal Maritime Commission, and the Civil Aeronautics Board (regulating “fares and entry”).

[45] Id. at 26.

[46] See George J. Stigler, The Theory of Economic Regulation, 2 Bell J. Econ. & Mgmt. Sci 3, 3 (1971) (“[A]s a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefit.”).

[47] See generally James M. Buchanan & Gordon Tullock, The Calculus of Consent: Logical Foundations of Constitutional Democracy (2004), https://www.econlib.org/library/Buchanan

/buchCv3.html.

[48] See Howard A. Shelanski, From Sector-Specific Regulation to Antitrust Law for US Telecommunications: The Prospects for Transition, 26 Telecomms. Pol’y 335 (2002) (describing the transition from regulation to deregulation in the telecommunications sector). See generally Alfred E. Kahn, The Economics of Regulation (1988).

[49] Carlton & Picker, supra note 5, at 58 (noting that antitrust law has been more durable than sector regulation).

[50] Id. at 34–37 (describing the myriad antitrust immunities carved out of Sherman Act liability in the first few decades after its passing, both by statute and judicial action).

[51] See Bruce H. Kobayashi & Joshua D. Wright, Antitrust Exemptions and Immunities in the Digital Economy, in The GAI Report on the Digital Economy (2020).

[52] See Philip E. Areeda & Herbert Hovenkamp, 1A Antitrust Law ¶ 241d (4th ed. 2013 & Supp. 2020).

[53] Id.

[54] Barak Orbach, The Implied Antitrust Immunity 2 (July 1, 2014) (unpublished manuscript), https://awa2015.concurrences.com/IMG/pdf/ssrn-id2447718.pdf (quoting United States v. Phila. Nat’l Bank, 374 U.S. 321, 350-51 (1963) (“Repeals of the antitrust laws by implication from a regulatory statute are strongly disfavored, and have only been found in cases of plain repugnancy between the antitrust and regulatory provisions.”).

[55] See, e.g., Justin (Gus) Hurwitz, Administrative Antitrust, 21 Geo. Mason L. Rev., 1191, 1193 (2014) (noting that the Court’s recent implied immunity cases “can be read together as advancing a very broad regulatory displacement standard for federal antitrust claims in fields subject to regulation.”).

[56] Verizon Commc’ns, Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko, LLP, 540 U.S. 398 (2004).

[57] The complaint alleged:

[Petitioner] has not afforded CLECs access to the local loop on a par with its own access. Among other things, [Petitioner] has filled orders of CLEC customers after fulfilling those for its own local phone service, has failed to fill in a timely manner, or not at all, a substantial number of orders for CLEC customers substantially identical in circumstances to its own local phone service customers for whom it has filled orders on a timely basis, and has systematically failed to inform CLECs of the status of their customers’ orders with [Petitioner].

Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko, L.L.P. v. Bell Atl. Corp., 294 F.3d 307, 313 (2d Cir. 2002).

[58] The district court twice dismissed the complaint for failure to state a claim. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the district court’s antitrust standing holding, but reversed the dismissal, holding that the plaintiff’s complaint may state a claim under the essential facilities doctrine or the monopoly leveraging doctrine. See id. at 326.

[59] “Section 601(b)(1) of the 1996 Act is an antitrust-specific saving clause providing that ‘nothing in this Act or the amendments made by this Act shall be construed to modify, impair, or supersede the applicability of any of the antitrust laws.’ This bars a finding of implied immunity.” Trinko, 540 U.S. at 406. See also Antitrust Modernization Comm’n, Report and Recommendations 339–40 (2007) (The Court’s holding in Trinko “is best understood only as a limit on refusal-to-deal claims under Section 2 of the Sherman Act; it does not displace the role of the antitrust laws in regulated industries.”).

[60] Trinko, 540 U.S. at 407.

[61] The Court noted that “[T]he Sherman Act “does not restrict the long recognized right of [a] trader or manufacturer engaged in an entirely private business, freely to exercise his own independent discretion as to parties with whom he will deal.” Id. at 408 (citing United States v. Colgate & Co., 250 U.S. 300, 307 (1919)). Furthermore,

[c]ompelling such firms to share the source of their advantage is in some tension with the underlying purpose of antitrust law, since it may lessen the incentive for the monopolist, the rival, or both to invest in those economically beneficial facilities. Enforced sharing also requires antitrust courts to act as central planners, identifying the proper price, quantity, and other terms of dealing—a role for which they are ill-suited. Moreover, compelling negotiation between competitors may facilitate the supreme evil of antitrust: collusion.

Id. at 407–08.

[62] “We conclude that Verizon’s alleged insufficient assistance in the provision of service to rivals is not a recognized antitrust claim under this Court’s existing refusal-to-deal precedents.” Id. at 410.

[63] Shelanski, supra note 6, at 694.

[64] As Shelanski notes, “The clear implication is that plaintiff had pleaded neither the facts nor the basic elements of any antitrust claims in his actual amended complaint and that the [Second Circuit] was adopting a very liberal pleading standard.” Id. at 692.

[65] Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41 (1957).

[66] Bell Atl. Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544 (2007).

[67] Id. at 557; see also Tellabs, Inc. v. Makor Issues & Rights, Ltd., 551 U.S. 308, 324 (2007)(“A complaint will survive, we hold, only if a reasonable person would deem the inference of scienter cogent and at least as compelling as any opposing inference one could draw from the facts alleged.”). For a discussion of the effects of the Court’s recent pleading cases, see Jonah Gelbach, Unlocking the Doors to Discovery?, 121 Yale L.J. 2270 (2012).

[68] See Shelanski, supra note 6, at 694:

Taken together, these facts put Trinko’s antitrust claim in an unsympathetic light from the outset. His section 2 claim was at best weak and duplicative of ongoing regulation; it was at worst an attempt to use antitrust law as a cover for bringing a class action suit he did not have standing to file under the 1996 act and to use that act as a basis for liability he would be unlikely to establish under antitrust law.

See also Pac. Bell Tel. Co. v. linkLine Commc’ns, 555 U.S. 438 (2009).

[69] See Shelanski, supra note 6, at 695–99.

[70] Trinko, 540 U.S. at 412.

Antitrust analysis must always be attuned to the particular structure and circumstances of the industry at issue. Part of that attention to economic context is an awareness of the significance of regulation . . . One factor of particular importance is the existence of a regulatory structure designed to deter and remedy anticompetitive harm. Where such a structure exists, the additional benefit to competition provided by antitrust enforcement will tend to be small, and it will be less plausible that the antitrust laws contemplate such additional scrutiny.

Id. at 411–12.

[71] See id. at 414:

Against the slight benefits of antitrust intervention here, we must weigh a realistic assessment of its cost. Under the best of circumstances, applying the requirements of § 2 “can be difficult” because “the means of illicit exclusion, like the means of legitimate competition, are myriad.” Mistaken inferences and the resulting false condemnations “are especially costly, because they chill the very conduct the antitrust laws are designed to protect.” The cost of false positives counsels against an undue expansion of §2 liability. . . . Even if the problem of false positives did not exist, conduct consisting of anticompetitive violations of §251 may be, as we have concluded with respect to above-cost predatory pricing schemes, “beyond the practical ability of a judicial tribunal to control.”

(internal citations omitted).

[72] See id. at 411: