Introduction

The antitrust laws were designed to regulate private conduct in order to promote competition and protect consumer welfare from exercises of monopoly power by firms. In other words, the antitrust laws, as “the magna carta of free enterprise,”[1] are designed primarily to regulate private conduct, not government conduct and public restraints of trade.[2] Private activity may still fall outside the scope of the antitrust laws when it is exempted specifically by Congress, heavily guided or influenced by the government, or relates to attempts to petition the government to take action.

Antitrust laws’ outer boundaries fall into three categories: (1) sectoral or industry-level exemptions, which single out an industry or business line from antitrust scrutiny; (2) state action immunity, which provides immunity for anticompetitive behavior by state governments and municipalities under certain conditions; and(3) Noerr-Pennington immunity, which aims to protect speech in the form of petitioning activity from antitrust liability.[3] The digital economy interfaces with the government in many respects; therefore, the antitrust laws’ reach—shaped by these exemptions and immunities—plays a clear role in guarding consumer welfare.

Antitrust’s goal of protecting competition is rarely, if ever, served by industry-specific antitrust exemptions; indeed, the consensus view is that such exemptions are much more likely to reduce consumer welfare than to enhance it. For example, the bipartisan Antitrust Modernization Commission has explained, “A proposed exemption should be recognized as a decision to sacrifice competition and consumer welfare. . . .”[4] Thus, any exemption from the antitrust laws should be narrowly tailored to address specific problems where procompetitive activity is likely to be deterred by the threat of mistaken antitrust liability, and blanket antitrust exemptions are economically unsound. This is because antitrust exemptions benefit small, concentrated interest groups while imposing costs broadly upon consumers at large in the form of higher prices, reduced output, lower quality, and reduced innovation.[5] Once protected from antitrust liability, private actors are free to collude with competitors and reduce innovation efforts once induced by vigorous competition. Moreover, codified antitrust exemptions are nearly impossible to abolish, resulting in long-term harm to competition in those specific industries.

There is less consensus concerning the appropriate scope of state action immunity from application of the federal antitrust laws.[6] While federal antitrust law must also comply with the principles of federalism, the precise contours of this judge-made immunity are not well-specified in practice.[7] At the core of state action immunity is the idea that federal antitrust laws must respect state sovereignty and allow states to apply their own approach to controlling competition, while simultaneously attempting to ensure that conduct does not harm consumers outside of the state.[8]

The antitrust laws also do not reach private conduct in the form of petitioning activity protected by the First Amendment. The Noerr-Pennington doctrine broadly immunizes petitioning activity directed toward one of the three branches of government. Like most market participants, members of the digital marketplace often petition the government, whether for legislation, agency rulemaking, or judicial decree. As such, Noerr-Pennington immunity remains important in understanding antitrust law in the digital economy. The intersection of antitrust and speech has played an important role in contemporary antitrust policy discussions. Concerns about large digital platforms’ potential ability and incentive to restrict speech have led enforcement agencies and Congress to focus on whether antitrust is an appropriate tool to regulate content moderation.[9] Digital platforms, which facilitate voluminous amounts of speech, have fused the topics of competition policy, censorship, and section 230 immunity. [10]

In Part 1, we examine industry specific antitrust exemptions, specifically proposed exemptions in the electronic payment systems and the journalism industries, and their potential negative effects on consumers. In Part 2, we discuss state action doctrine and dual federal and state antitrust enforcement in the digital economy. In Part 3, we examine the Noerr-Pennington doctrine, the sham exception, and two specific applications: patent holdup injunctions and citizen petitions.

I. Industry-Specific and Sectoral Antitrust Exemptions

Antitrust exemptions provide limited immunity to specific industries from antitrust regulations. Most antitrust exemptions are economically unsound and decrease consumer welfare by diminishing competition and innovation in the given industry. What follows is an explanation of industry specific antitrust exemptions and a discussion of how proposals for exemptions in the credit card and journalism industries will harm consumers.

A. Antitrust Exemptions for Industries Harm Consumers

Antitrust laws seek to foster competition and thereby maximize consumer welfare.[11] However, broad exemptions of specific industries from the antitrust laws do not serve this goal. As the Antitrust Modernization Commission explained, “A proposed exemption should be recognized as a decision to sacrifice competition and consumer welfare. . . .”[12] Antitrust exemptions benefit “small concentrated interest groups while imposing costs broadly upon consumers at large.”[13] These costs generally manifest as higher prices, reduced output, lower quality, and reduced innovation.[14]

Congress has created antitrust exemptions for specific industries such as railroads,[15] insurance companies,[16] ocean shippers,[17] certain agricultural cooperatives,[18] and non-profits.[19] Moreover, the FTC Act explicitly exempts banks, savings and loans institutions, federal credit unions, common carriers, domestic and foreign air carriers—as they are regulated under different federal law.[20]

Broad antitrust exemptions are not only economically unsound, but also do not protect procompetitive purposes already protected by the Sherman Act. [21] Immunizing industries from antitrust liability allows for coordination among rivals. These cartels have the power to “jointly set prices or other competitive terms” which will “tend to increase the prices for services beyond what they would otherwise be in the presence of competition.”[22] Competitors will no longer have incentives to innovate, and consumers will suffer from the lack of cost reduction or increased product quality.

Industry-level exemptions promote rent-seeking and often lead to less competition, not more. Antitrust exemptions create a classic public-choice problem. Industries with special exemptions are highly concentrated and often times highly political, therefore, the individual groups benefit greatly from the exemptions’ privileges. [23] Consumers, on the other hand, may not feel the harm of higher prices as strongly on an individual level, even though the aggregate harm to consumer welfare is significant. Therefore, individual consumers have little incentive to pursue repeals of existing exemptions.[24]

Even if consumers had an individual incentive to repeal harmful antitrust exemptions, the actual process is difficult. Exemptions are not removed rapidly, as it takes time for industries to alter the fundamental aspects of their businesses.[25] While exemptions might have been enacted to protect competition in certain industries, they now pose a dangerous risk of institutionalizing anticompetitive conduct.[26] Antitrust exemptions replace competition with government regulation thereby reducing incentives to compete vigorously through reduced price or improved product quality.[27]

The case for industry-specific antitrust exemptions is weak. The argument that specific industry exemptions are necessary to protect facially anticompetitive acts that actually have procompetitive effects[28] is rendered dubious by the fact that courts analyze most conduct under the rule of reason.[29] Moreover, original justifications for certain industry exemptions are no longer backed by economic theory. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century some exemptions were created with the idea that “regulation was preferable to competition or that there were natural monopolies that needed to be controlled.”[30] However, it is evident that “consumers benefit most when competitors freely compete”; therefore, economic regulations should focus on “preserving a competitive marketplace” rather than supporting anticompetitive collusion.[31] Industry exemptions replace vigorous competition with government regulation.[32]

B. Recently Proposed Exemptions in Digital or High-Tech Markets

This section will discuss proposed antitrust immunities related to the digital economy. One proposal is to grant merchants the ability to collectively bargain with credit card issuers. Another is a proposal to allow news publishers to collectively bargain with digital media platforms. Such proposals provide no benefits for consumers and would harm competition in these markets.

1. Credit Cards & Merchant Antitrust Immunity

Merchants have long argued for antitrust exemptions to set lower interchange fees. An interchange fee is the rate paid between the merchant’s bank (acquiring bank) and the consumer’s bank (issuing bank). Because acquiring banks will charge the merchant a fee for handling the payment equivalent to the interchange fee, merchants are usually responsible for paying the interchange fee.

Merchants are calling for regulations to lessen their burden of paying interchange fees. They argue that card companies rarely discuss the interchange fee with them and present the fees as a “take it or leave it offer.”[33] Merchants contend that their only choices are to lose business form holders of those cards or incur increased costs. Merchants may decide not to accept certain brands or to charge a higher price to customers to cover the interchange fee. However, because most merchants do not wish to face issues by either denying certain card brands or charging certain customers more, they tend to charge all customers the same higher price.[34]

In 2009, the House of Representatives proposed antitrust exemptions allowing merchant-level collusion. The Credit Card Fair Fee Act of 2009 proposed a limited antitrust immunity for “single covered electronic payment system and any merchants [to] jointly negotiate and agree upon the rates and terms for access to the covered electronic payment system.”[35] The credit card companies would also jointly decide “the proportionate division among themselves of paid access fees.” Proponents argued that by allowing merchants to collectively negotiate prices, they can exercise greater bargaining power against large credit card companies.[36] These proposed antitrust immunities for merchants have been reinvigorated by both the Payment Card Interchange Fee and Merchant Discount Antitrust Litigation and the Supreme Court’s decision in Ohio v. American Express.[37]

Giving merchants the power to arbitrarily set interchange fees is bound to harm credit card holders. First, allowing merchants to collude on interchange fees will reduce vigorous competition at the merchant level. Even if immunity for merchant-level collusion did result in a low interchange fee “that does not make such collusion desirable.”[38] Even though the intended outcome of the proposed antitrust exemption is to lower the cost of transaction for consumers by improving rates for merchants, there is no guarantee that merchants will pass on the price reduction to consumers.[39] Allowing merchants to set lower interchange fees will diminish innovation at the merchant level.

Moreover, arbitrarily setting interchange fees will at best help only merchants, while most likely harming consumers. Reducing interchange fees may reduce merchant costs, but they will “impose those costs on other network actors, especially consumers.”[40] Having merchants pay the interchange fee “permits the issuer to attract more cardholders than it would be able to if it were forced to impose higher direct fees on cardholders.”[41]

Even though interchange fees have been on the rise since 1990,[42] which has increased merchants’ cost, the current interchange fees are based on market costs for completing credit card transactions.[43] Interchange fees play an important role in “supporting electronic payment systems.”[44] Credit card companies use the funds from interchange fees to “recoup some operating costs without imposing higher direct costs (annual fees and the like) on cardholders.”[45] Having interchange fees paid by merchants “ensures that merchants pay for the benefits they receive and is essential to the efficient and effective operation of the system.”[46]

Allowing merchants to collectively decide arbitrary rates no longer ties the interchange fee to market conditions. Such an exemption would “place open-loop payment card systems at a competitive disadvantage in the marketplace.”[47] Exempting merchant collusion would distort the competitive balance in the payment card systems industry.[48]

Moreover, evidence shows that arbitrarily setting interchange fees does not benefit consumers. In 2001, the Reserve Bank of Australia (“RBA”) began regulating interchange fees. Specifically, the RBA enacted interchange fee caps with the goal of reducing credit card usage by shifting “costs of the card network from merchants to consumers.”[49] Ex post analysis of these regulations showed that credit card usage did not decline, and that there was “no discernible decrease in retail prices.”[50] Therefore, only merchants benefit from interchange caps.

If interchange fees are set arbitrarily low, credit card companies will not receive the necessary payments from merchants, and thus might be forced to cut costs by increasing annual fees and interest payments, or by reducing cardholder benefits and customer support.[51] Moreover, credit card companies might cut off certain cardholders in an attempt to reduce risk exposure.[52] In Australia, annual fees for credit card holders increased significantly following the interchange fee regulation.[53]

Interchange fee regulation proposals in the U.S. differ from those in Australia as the Credit Card Act proposes to give merchants, not a government agency, price setting power for interchange fees. Regardless, a similar harm would be felt by U.S. consumers given that merchant antitrust immunity will result in arbitrarily low interchange fees.[54] Regulations to allow “bilateral bargaining between merchants and the card networks” are not guaranteed to result in greater benefits to card holders than the current system already does.[55]

2. News & Journalism Antitrust Exemptions

New antitrust exemptions have been considered for the news industry. The House proposed the Journalism Competition & Preservation Act of 2019 which allows print or digital news publishers to collectively negotiate with digital platforms—like Google and Facebook—regarding the terms on which the digital platforms may distribute the news publishers content.[56] The bill would provide a temporary 4-year safe harbor window where the news publishers would be exempt from the antitrust laws for collectively withholding content from, or collectively negotiating with, the digital platforms regarding distribution terms.[57]

Proponents of the exemption acknowledge its explicit goal is to displace competition for the purpose of “helping newspapers survive.”[58] The regulation would “establish an even playing field for negotiation with online platforms . . . improv[ing] the quality and accessibility of reporting.”[59] Proponents further contend that because Google and Facebook account collectively for up to approximately 60% of the digital advertising economy,[60] news publishers have a reduced bargaining position. This exemption would give news publishers the power to collectively demand the digital platforms pay more for their content, provide more data and brand visibility, and give new publishers control of their content on the platforms.

Giving antitrust immunity to news publishers enables them to maintain inefficient business models that harm consumers. For example, in 1969, the Newspaper Preservation Act (NPA) was enacted to provide limited antitrust immunity for some joint operating agreements (JOA) between newspapers to combine certain business operations.[61] Congress enacted the NPA to help two California newspapers survive in the same city.[62] By combining business operations, the newspaper companies could reduce overhead costs, while still competing for reports and editorial policies.[63] Combining business operations allowed the newspapers to participate in anticompetitive price fixing of subscription prices and advertising rates.[64]

The Assistant Attorney General for the Antitrust Division Richard W. McLaren strongly opposed giving antitrust immunity to newspapers for serval reasons.[65] First, the NPA “removes newspapers from the judgement of the marketplace,” which is specifically important given new media’s role in free speech and the open market for exchanging ideas.[66] Second, without the NPA, competitors would have to seek out alternatives methods to survive in the market, such as innovation or acquisition by an outsider.[67] Antitrust immunity allows the newspapers to escape competition and to survive without making any real improvements to the business. The “JOAs create[d] a shared monopoly that increases market-entry barriers” and allowed two close competitors to be given “immunized price-fixing.”[68] Finally, the NPA would create incentives for greater rent-seeking for other media to seek antitrust immunity.[69]

The results of the NPA are instructive. The NPA negatively impacted consumer welfare—like most other industry-specific antitrust exemptions. It “failed to save papers in the long run, harmed consumers by increasing circulation and advertising prices between 15-25 percent, and was misused in a variety of ways [for] corporate benefit that were not intended when the law was enacted.”[70]

Much like the 1969 NPA, the Journalism Competition & Preservation Act of 2019 would harm consumers and the news media market if enacted. First, this proposed antitrust immunity establishes a news media cartel that sets prices on media platforms.[71] It “transfer[s] surplus from online platforms to news organizations, which will likely result in higher content costs for these platforms, as well as provisions that will stifle the ability to innovate.”[72]

Second, the increased advertisement prices created by the news publishers would become an entry barrier for small news publishers, resulting in less diverse news options for consumers. Advertisement prices for online platforms are low and have decreased by 40% since 2010, which “suggest[s] that Internet advertising is perhaps a more competitive segment than print advertising.”[73] Lower advertising prices benefit consumers by decreasing costs to publishers and allowing for more publishers to be able to advertise on the digital platforms. The low cost of advertising on digital platforms “opens the door to small firms” allowing them to “grow more quickly and easily.”[74] “Increased choice and access to more businesses” benefits consumers.[75] If news publishers collude on terms with digital platforms, larger publishers will create better positions for themselves and make advertising more expensive for smaller publishers, which will force smaller news publishers to leave the digital platforms.

Policies and terms created by a news publisher cartel would likely raise prices of digital advertising, harming both consumers and advertisers.[76] Such an antitrust exemption will enable news publishers to preserve outdated business models, which will “only slow down innovation and the response of the news industry to changing economical and social realities.”[77]

II. Antitrust & Federalism: State Action Doctrine

State action immunity authorizes states to enact industry specific regulations that are anticompetitive—for example by allowing price fixing and other forms of anticompetitive collusion,[78] by allowing incumbent providers to erect regulatory restrictions on competition,[79] and by allowing anticompetitive mergers to be consummated.[80] It carves out from antitrust liability certain conduct by private firms that is heavily guided by state action under certain conditions. This section explains state action doctrine and its negative spillover effects on consumers in other jurisdictions. It then describes how this sometimes strenuous relationship between state action doctrine, federalism, and comity is depicted in the role of state attorneys general in federal antitrust disputes.

A. Antitrust Immunity Under the State Action Doctrine

Under the state action doctrine, states and municipal authorities are themselves immune from federal antitrust laws. The Supreme Court has protected state sovereignty and the principles of federalism by broadly holding that the Sherman Act is directed against “individual and not state action.”[81] Therefore, the antitrust laws cannot abrogate a state action that supplants competition with regulation, regardless of its anticompetitive effect or intent.[82]

While the state action doctrine allows the state to replace competition with regulation, the state may not shield illegal conduct from the Sherman Act “by authorizing [private parties] to violate it, or by declaring that their action is lawful.”[83] Therefore, the Sherman Act preempts state regulation that “mandates or authorizes conduct that necessarily constitutes a violation of the antitrust laws in all cases, or . . . places irresistible pressure on a private party to violate the antitrust laws in order to comply with the statute.”[84]

Private parties are only immunized from an antitrust suit under state action if they show that (1) the state clearly articulated an express intent to displace competition with a regulatory scheme and (2) the state actively supervises that scheme.[85] The clear articulation is often explained as a mechanism to increase the extent to which state governments are held politically accountable for the anticompetitive effects of regulations by forcing them to be transparent about the anticompetitive intent of the legislation.[86] The active supervision requirement has been explained as a penalty option that disincentivizes anticompetitive state legislation by making it more costly for both states and the private parties that stand to benefit from the anticompetitive regulations.[87]

However, basing antitrust immunity on active supervision of the state does not necessarily serve as a deterrent to anticompetitive regulations.[88] If state regulations are in fact anticompetitive schemes to reward politically powerful interest groups, then this requirement conditions antitrust immunity on actions of the entity that created the anticompetitive scheme.[89] Moreover, active state supervision can be especially costly, which can harm both consumers and the regulated firms.[90]

B. Spillover Effects and Antitrust Federalism

The current state action doctrine does not enable jurisdictional competition or promote the principles of federalism because it does not account for the spillover effects of anticompetitive state regulation. Judge Easterbrook examined the Court’s state action holdings and found that the Court’s rulings were indifferent as to whether the effects of the regulation were actually internalized by the regulating state.[91] Allowing states to enact anticompetitive legislation reduced the extent and effectiveness of competition among the states, and thereby increased the cost of exit and relocation.[92]

This nature of the spillover effect is exemplified in Parker v. Brown.[93] The state action doctrine was used to uphold a California regulation which authorized a raisin cartel. California raisin growers benefited greatly from that ability to price fix. However, over 90% of the grapes were exported outside of California—nationally and internationally—making the impact of the California raisin regulation reach beyond state lines.[94] The regulation harmed a large number of consumers outside of California while only benefiting a small number of private interest parties within the state.

State action doctrine, although meant to preserve that state’s independence, actually allows the state to reap the benefits of the anticompetitive regulation while displacing the costs onto other states.[95] Therefore, it is worth considering if the current state action doctrine should be thought of differently, in a way that fully takes into accounts issues of federalism. Judge Easterbrook proposes a state action rule which considers the spillover effect of anticompetitive state regulation. Instead of examining clear articulation and active supervision, the Court would uphold an anticompetitive state regulation as long as its anticompetitive effects are internalized by that state’s residents.[96] Aligning state action doctrine with the economics of federalism will not only maintain states’ roles in antitrust, but also ensure that state antitrust exemptions have a diminished negative impact on consumer welfare. Analyzing the anticompetitive overcharge of regulations is also more administrable than attempting to analyze the regulations under the dormant Commerce Clause.[97] Considered under Easterbrook’s approach, Parker’s California raisin prorate program would be subject to antitrust scrutiny because the regulation’s costs were not internalized.

State regulation of seemingly local competition is likely to effect more than just the economy of that specific state. When states grant antitrust immunities in situations involving interstate commerce, the state is exporting the anticompetitive effects of its regulations to citizens outside its own borders. Without accounting for the federal interest in an integrated national economy, state action doctrine far surpasses its narrow purpose of supervising local competition.

C. The Appropriate Role of State Attorneys General in Federal Antitrust Disputes

Federalism most often refers to the vertical relationship between the federal government and the states. Divergent viewpoints among antitrust enforcers can strain the system, thus comity and deference are crucial to efficient antitrust enforcement. A merger or acquisition is often scrutinized by multiple enforcers with multi-dimensional relationships.

For example, the Sprint/T-Mobile merger involved the Antitrust Division and Federal Communications Commission, who share a horizontal relationship, and state attorneys general, with which the federal agencies share a vertical relationship. Disagreement between enforcers may occur at either level.[98] The merger between the two telecommunications firms was cleared by the FCC, the Antitrust Division, and ten state attorneys general.[99] Although a settlement agreement—which required divestitures—was in the process of being approved, several other state attorneys general filed a lawsuit to block the merger anyway.[100] Assistant Attorney General Makan Delrahim questioned the relief sought by the states,[101] citing the federal agencies’ expertise in the matter.[102] He noted that “a minority of states and the District of Columbia” were “trying to undo [the nationwide settlement],” a situation he believed was “odd.”[103] Delrahim reaffirmed states’ rights to sue for antitrust violations but criticized their attempt to seek relief inconsistent with the federal government’s settlement.[104]

States may also enter settlement agreements with merging parties that are repugnant to sound antitrust enforcement. For example, in UnitedHealth Group/Sierra Health Services, the Nevada Attorney General required the merged firm to submit $15 million in charitable contributions which were not related to any antitrust violation.[105] Similarly, Massachusetts entered a settlement agreement with two hospitals that required increased spending on select programs and the creation of other projects and programs unrelated to antitrust concerns.[106]

On the other hand, state antitrust enforcement can play a useful role in supplementing federal antitrust enforcement. First, the use of state autonomy within a federal system allows state and local governments to act as social “laboratories,” where laws and policies are created and tested at the state level of the democratic system, in a manner similar (in theory, at least) to the scientific method.[107] Thus, even if states enter into agreements with merging parties that the federal authorities view as anticompetitive or that impose ineffective remedies for the anticompetitive effects that would be generated by the merger, the information generated by such actions can be invaluable inputs into retrospective analyses of the competitive effects of mergers. These analyses are based on causal empirical designs which require both observation of post-merger price and quality effects from consummated mergers and the ability to compare these effects with a credible control group.[108] For example, state interventions such as COPA or Certificate on Need Laws that allow hospital mergers that generate competitive effects in local geographic markets facilitate retrospective studies of hospital mergers that can be used to validate and improve the economic models and other tools used to predict merger effects.[109]

Second, in a system of federalism, the state enforcement of both the state and federal antitrust laws can be a valuable complementary resource that supplements scarce federal resources. Conflicts between the federal and state antitrust authorities are generated by the use of a cooperative or “marble cake” approach to federalism, where the tasks of the state and federal agencies are relatively undefined, overlapping, and imperfectly coordinated. In contrast, a “dual” or “layer cake” federalism approach, where power is divided ex-ante between the federal and state governments in clearly defined terms, can mitigate direct conflicts between state and federal authorities discussed above.

One such approach would be to divide authority for mergers on whether the effects of the transaction were contained within a state.[110] For example, merger transactions with largely intra-state competitive effects would be left to the appropriate state authority to investigate and challenge if found to be anticompetitive. This would include many small mergers with local within-state geographic markets. But it would also include some larger mergers with intra-state effects, including large hospital mergers.[111] Responsibility for mergers with interstate implications, such as the Sprint/T-Mobile merger mentioned above, would be allocated to the federal agencies.[112]

III. Noerr-Pennington Immunity

The Sherman Act’s applicability to only anticompetitive private conduct also underlies the Noerr-Pennington doctrine. Formed in the 1960s, Noerr-Pennington is a doctrine rooted in the First Amendment that shelters from antitrust liability non-sham petitions attempting to influence government action. What follows is a discussion of the doctrine’s history, the sham exception, patent holdup, and citizen petitions.

A. A Brief History of the Noerr-Pennington Doctrine

The Noerr-Pennington doctrine emerged from the Supreme Court’s holdings in Eastern Railroad Presidents Conference v. Noerr Motor Freight, Inc.,[113] and United Mine Workers v. Pennington.[114] Both cases were decided in the early 1960s, and since, the Court has decided several cases further shaping the doctrine.

In Noerr, members of the trucking industry sued railroad companies for commencing a publicity campaign aimed at influencing Pennsylvania’s regulation of the trucking industry.[115] The trucking-industry plaintiffs challenged the railroads’ campaign under sections one and two of the Sherman Act.[116] After trial, the district court entered judgment for the trucking industry plaintiffs, noting that the railroads campaign was both “malicious and fraudulent.”[117] Indeed, the railroads had disguised their involvement in the campaign by using a third-party publicity firm.[118] The district court also concluded that any harm delivered by the passage of duly-enacted laws could not be attributed to the defendants, thus damages were limited to the “destruction of the truckers’ goodwill.”[119]

The Supreme Court held that, even if the sole purpose of the campaign was to harm rivals, the right to petition the government removed the railroads’ publicity campaign from the Sherman Act’s coverage.[120] Neither did the railroads’ use of the “third-party technique” limit the breadth of the right to petition, although the Court agreed that this approach fell “far short of the ethical standards generally approved in this country.”[121]

The Court emphasized two justifications for its holding that the Sherman Act “does not apply to mere group solicitation of governmental action.”[122] First, it noted the need for discourse between private parties and the government in a representative democracy.[123] Specifically, the Court referenced both the “right of the people to inform their representatives in government” and the “right to petition.”[124] Second, it connected this principle with the interpretive canon of constitutional avoidance.[125] The dynamic between the First Amendment right to petition and the Court’s interpretation of the Sherman Act was clear: First Amendment principles shelter from antitrust liability attempts to “influence legislation by a campaign of publicity.”[126] But the Court included one important caveat: petitioning activity that is a “mere sham” remained squarely within the Sherman Act’s scope.[127]

Several years later, the Court addressed Noerr’s application to petitions directed toward the executive branch.[128] In Pennington, small-mine operators alleged that large-mine operators and the coal miners’ union colluded to eliminate competition from the small mines.[129] As part of the conspiracy, both the union and large-mine operators successfully petitioned the Secretary of Labor to institute a minimum wage requirement for mining operators contracting with the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA).[130]

The Court rejected the lower courts’ position that, because the efforts to secure a minimum wage requirement were part of a larger conspiracy, Noerr did not apply.[131] In doing so, the Court reaffirmed the principle, first announced in Noerr, that harm delivered by government action, whether legislative or executive, could not be assigned to a defendant who petitioned for that action.[132]

After Noerr and Pennington, non-sham petitioning activity, directed toward either the executive or legislative branch, fell outside the Sherman Act’s boundaries. Later, in California Motor Transport Co. v. Trucking Unlimited, the Court affirmed the doctrine’s application to both administrative agencies and the judicial branch.[133]

In Trucking Unlimited, a clash between two groups of rival highway carriers gave rise to a private antitrust action.[134] The plaintiffs alleged that the defendants conspired to automatically challenge plaintiffs’ applications for transfer rights—a necessary step to comply with the applicable commercial law.[135] Further, the plaintiffs alleged that this scheme denied them access to the appropriate tribunals and thereby harmed their respective businesses.[136] At the motion to dismiss stage, the defendants argued that their activities were immune under the Noerr-Pennington doctrine; the district court agreed and dismissed the case.[137] The Supreme Court disagreed. The Court held that, taking the plaintiffs allegations at face value, the defendants’ conduct came within the sham exception because a “pattern of baseless, repetitive claims . . . cannot acquire immunity . . . under the umbrella of ‘political expression.’”[138]

Trucking Unlimited described the sham exception in a situation where the defendant uses a series of administrative and court filings devised to harm competitors. In Professional Real Estate Investors, Inc. v. Columbia Pictures Industries (PRE), the Court introduced a two-step sequential test for determining whether a single lawsuit, rather than a course of conduct, was a mere sham and thus outside Noerr-Pennington’s coverage. The Court held that for a lawsuit to be a sham, it must be (1) “objectively baseless” and (2) intended to generate an anticompetitive effect through the process, not the outcome, of the litigation.[139] Applying this two-step framework to the facts, the Court affirmed the court of appeals’ holding that the copyright infringement suit under scrutiny was filed with probable cause and thus did not fall within the sham exception.[140]

Noerr-Pennington’s scope reflects the assumption that the Sherman Act applies to private conduct—generally, the Act does not apply to anticompetitive government action.[141] As an extension, private conduct aimed at influencing government action, even if it is anticompetitive, receives protection because the Constitution preserves the right to petition. Immunity is not extended in cases where the private conduct itself causes the anticompetitive harm. Nor is immunity extended where the private conduct directly influences private conduct which, in turn, indirectly influences government action. These distinctions are not always clear, but each has been addressed by the Court.

In Allied Tube & Conduit Corp. v. Indian Head, Inc., the Court addressed the distinction between privately influenced government action that, in turn, caused anticompetitive harm and privately caused harm where the government’s involvement was indirect. There, the defendant’s conspiratorial conduct that sought to influence a standard-setting body did not receive Noerr-Pennington immunity, even though the standard was likely to be adopted by the government.[142]

Two years later, in FTC v. Superior Court Trial Lawyers Association, the Court declined to extend immunity to a group boycott because the desired legislative action was the remedy to the anticompetitive conduct, not the source.[143] This holding once again reaffirmed the principle underpinning Noerr-Pennington: The government’s immunity under the Sherman Act is the touchstone; privately caused anticompetitive harm remains subject to liability.

B. Sham Litigation

In the litigation context, the PRE two-step sequential test provides courts with a roadmap for determining whether a litigation is a mere sham and therefore subject to antitrust scrutiny. Notwithstanding the PRE test’s requirement of objective baselessness, economic analysis suggests that even lawsuits filed with probable cause should be subject to antitrust scrutiny. This section discusses the PRE test and its relationship with the underlying economics.

The Sherman Act is notably concise—a characteristic that invites greater judicial discretion than almost any other federal statute. In recent decades, the Supreme Court has adopted economics as the north star in antitrust statutory interpretation. An economic analysis of sham litigation offers helpful insight into the Noerr-Pennington doctrine’s actual effects, but as a quasi-constitutional doctrine, a purely economic approach—used to outline substantive offenses—may not be equally applicable. Whether economics should shape the First Amendment’s impression on federal statutes is not addressed by this Report. Instead, economic analysis is offered as a useful way to consider the sham exception and its impact on antitrust enforcement.

Firms proceed with litigation when the expected value from a judgment and its direct effects outweigh the expected costs of litigation.[144] Strategic litigation occurs when the expected value of a judgment on the merits alone does not outweigh litigation costs.[145] Rather, an effect collateral to the judgment produces value for the firm, increasing the expected value to a level greater than litigation costs.[146] An economic approach must address strategic litigation because it involves mixed motives (i.e., merits judgment plus collateral effect), which, in some cases, may include an anticompetitive collateral effect.

Using adjudicative processes for predatory purposes is a nonprice method of predation and a form of strategic litigation.[147] The predator uses the process of litigation to inflict costs, delays, and other business harms on potential entrants.[148] The greater the disparity between the predator and the victim, the more effective nonprice predation will be.[149] This follows because litigation costs are not tied to variable costs, thus the large predator incurs costs at a rate lower than its victim in terms of cost per dollar of sales.[150]

Defining sham litigation solely by the existence of an anticompetitive collateral effect—one that is a necessary condition for entering the litigation—may lead to a chilling effect on legitimate lawsuits. Under this approach, some lawsuits with an overall positive expected value may still be shams, in the sense that they would not have been filed but-for the anticompetitive effect.[151] But subjecting such lawsuits to antitrust liability may be undesirable because it could deter legitimate suits, which would be seen as a restriction on access to the courts.[152]

Before PRE’s objective-baselessness test, some courts applied a broader test resembling a purely economic approach. In Grip-Pak, Inc. v. Illinois Tool Works, Inc., Judge Posner reasoned that because the First Amendment did not immunize conduct falling under the tort of abuse of process—which unlike malicious prosecution did not require a showing of probable cause—neither did the First Amendment immunize conduct based on probable cause alone.[153] He extended this principle to the sham exception and recognized that “[m]any claims not wholly groundless would never be sued on for their own sake; the stakes, discounted by the probability of winning, would be too low to repay the investment in litigation.”[154] His approach rejected the idea that probable cause for filing a lawsuit necessarily renders that lawsuit a non-sham.[155] Judge Posner’s analysis immunizes all lawsuits with a positive expected value, but allows negative expected value lawsuits with probable cause to be challenged under the sham exception.

In short, viewing Noerr-Pennington’s sham exception through an economic lens, it is entirely possible that anticompetitive litigation could hide behind the shield of the mere existence of probable cause (not objectively baseless) or even behind suits with net positive expected value. Whether, as a matter of statutory interpretation (and First Amendment overlays), the sham exception should include non-baseless claims when a significant portion of value is derived from the anticompetitive collateral effect is a separate matter—one that the Supreme Court decided in PRE. Under the PRE test, the first element of the sham exception requires objective baselessness; undoubtedly then, some lawsuits filed with anticompetitive intent sail away from liability under the Noerr-Pennington flag.

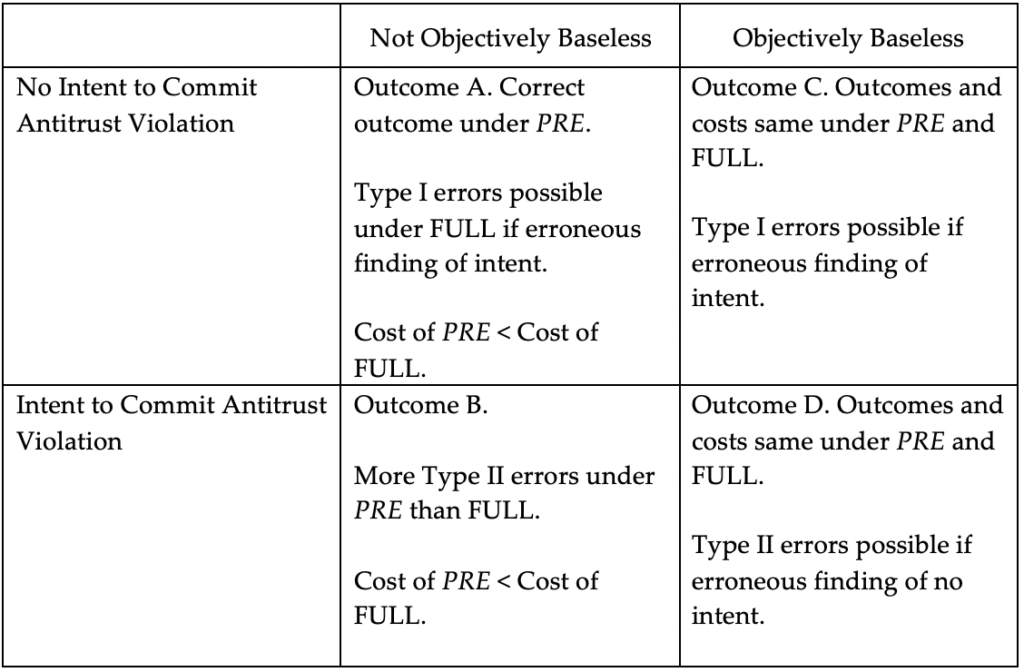

This not the end of the matter, however, because under an error-cost framework, the PRE test may still be the most efficient, even though some anticompetitive conduct may be immunized. The PRE test contains two variables—objective baselessness and subjective intent—that produce four outcomes, as reproduced below.[156]

Under PRE, when a court concludes that a lawsuit is not objectively baseless, the inquiry terminates and the issue of intent is not considered. In contrast, a finding that the lawsuit is objectively baseless causes the inquiry to proceed to the intent analysis. Thus, comparing outcomes A and B reveals the key differences between the PRE test and an economics-based test (i.e., anticompetitive purpose defines sham), whereas outcomes C and D will produce identical results under both tests. Ultimately, moving to the Court’s sequential PRE test is efficient if the marginal increase in the costs of type II errors in outcome B are outweighed by administrative and litigation cost savings plus the marginal reduction in the costs of type I errors in outcome A.[157] Measuring the magnitude of administrative, litigation, and error costs, and thereby drawing a conclusion about the PRE test’s efficiency, is a task beyond the scope of this Report. The key takeaway is that either the PRE test or an economics-based test akin to that applied in Grip-Pak may be more efficient, but further research is needed before making a conclusion.

C. Patent Holdup and Injunctions

Noerr-Pennington immunity and specifically sham litigation are often discussed in the patent context. Patent holders possess the right to exclude and to seek injunctive relief.[158] Patent infringement suits in the standard essential patent context, the ability of a patentee to receive injunctive relief, and licenses negotiated in the shadow of an injunction raise difficult questions about antitrust law’s bounds and the intersection between intellectual property and antitrust law.[159]

Standard-setting organizations (SSOs) play an important role in the economy by setting standards that facilitate the adoption of new technology. These standards take a variety of forms, including interoperability and performance standards. Consumers often benefit from standard-setting. For example, interoperability standards benefit consumers by generating network effects—value derived from increases in the number of product users.[160]

Sometimes technology incorporated into a standard is subject to intellectual property rights, typically patents. SSOs regularly require members to disclose patented technology before potential incorporation. The SSO will then identify the standard-essential patents (SEPs) and usually require the SEP holder to agree to license their patents on fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms. The evidence shows that SSOs adapt their intellectual property right policies to balance the interests of both contributing and adopting members.[161] Nevertheless, sometimes patentees and licensees may encounter difficulty agreeing on what constitutes FRAND-level royalties. In such cases, a patentee may decide to file a patent infringement suit against the user of the standard. The threat of litigation or filing of a lawsuit may incentivize the parties to reach an agreement, but on occasion the patentee proceeds with the litigation, seeking an injunction against the alleged infringer.

The application of Noerr-Pennington is straightforward when a licensee claims the patentee violated the antitrust laws by seeking the injunction—a patent infringement suit is not subject to antitrust liability, unless it is a sham or the patent was acquired by fraud.[162] Thus, asking a court for relief is exactly the type of petitioning the First Amendment protects.[163] Moreover, concerns that patent infringement suits may facilitate anticompetitive behavior when the patentee possesses a FRAND-encumbered SEP may be adequately addressed by contract and injunction law.[164]

Some argue that patentees waive their rights under Noerr when agreeing to license their patents on FRAND terms.[165] Under that theory, an SEP holder who agreed to FRAND terms is barred from pursuing an injunction against the standard user. Others have argued creatively that an antitrust plaintiff can evade Noerr-Pennington immunity by alleging a “monopoly broth” of conduct violating Section 2 of the Sherman Act—a broth that includes, but is not limited to, seeking the injunction. This theory of antitrust liability has failed to gain traction in courts, though, being rejected by several U.S. courts of appeal.[166]

The “monopoly broth” theory has, however, found limited traction in antitrust enforcement agencies—particularly the Federal Trade Commission. In 2012, the FTC submitted an amicus brief supporting a district court’s denial of injunctive relief for an SEP holder who made FRAND commitments.[167] Beyond advocacy, the FTC has entered into a number of settlements on the theory that seeking an injunction alone constitutes an unfair method of competition under Section 5 of the FTC Act. In 2008, the FTC reached a settlement with Negotiated Data Solutions (N-Data) for an alleged Section 5 violation when it reneged on a commitment to license its technology for a one-time $1,000 fee and sought to enforce its patents to obtain higher royalties.[168] In two other cases—Bosch and Google—FTC required defendants to withdraw from claims seeking injunctive relief for patent infringement respecting FRAND-encumbered SEPs. In Bosch, the FTC emphasized “the tension between offering a FRAND commitment and seeking injunctive relief.”[169] The next year, the FTC entered a consent agreement with Google, barring its pursuit of injunctions for FRAND-encumbered SEPs it acquired via its acquisition of Motorola Mobility.[170] Commissioner Ohlhausen issued a dissenting statement arguing, inter alia, that the consent agreement was ill-advised because Noerr-Pennington immunized Google’s patent litigation.[171]

Although the FTC has previously treated certain injunction suits as Section 5 violations, the 2015 Policy Statement on Section 5 makes similar actions doubtful in the future. The Statement announces the FTC’s commitment to avoiding using Section 5 to remedy conduct covered by traditional antitrust laws.[172] Breach of a FRAND commitment attained through the competitive process, rather than through deceit, is not a violation under traditional antitrust laws.[173] Thus, the FTC is unlikely to mobilize Section 5 to attack such conduct in the future.[174]

D. Citizen Petitions

The Hatch-Waxman Act created a distinct regulatory scheme for securing FDA approval for pharmaceutical drugs—a scheme further complicated by patent and antitrust overlays.[175] The citizen petition process, which allows interested parties to comment on drug applications, may be used anticompetitively, much like sham litigation.

Pharmaceutical companies must obtain FDA approval before marketing new drugs. To market a new drug, a company must file a New Drug Application (NDA).[176] The NDA contains a list of patents associated with the new drug.[177] Subsequently, a generic manufacturer may file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA).[178] During the ANDA process, the generic manufacturer often selects what is called Paragraph IV certification—an attestation that the brand name drug’s patents are invalid, thus generic entry is unhindered.[179] Importantly, Paragraph IV certification is incentivized by a 180-day exclusivity window granted to the first ANDA applicant.[180]

Obviously, the patent holders (brand name drugs) accrue significant profits during the life of their patents. An early challenge to those patents threatens to cut off substantial amounts of revenue. Not surprisingly, then, brand name manufacturers employ various techniques to extend this period of exclusivity. One such technique is the filing of citizen petitions to the FDA, a process grounded in the right to petition and the Administrative Procedure Act.[181] The FDA receives comments on ANDA applications and some brand name manufacturers have used this process to attempt to delay generic entry.[182] In addition to citizen petitions, a brand name manufacturer may file a patent infringement lawsuit against the party who filed the Paragraph IV certification. In fact, the decision to do so triggers a thirty-month stay, incentivizing brand name manufacturers to file lawsuits defending their patents.

When considering an ANDA, the FDA must assess whether the proposed generic drug is a bioequivalent to the brand name drug.[183] Thus, some brand name manufacturers use the citizen petition process to argue that the generic drug is not bioequivalent. In some cases, these petitions are frivolous.[184] Clearly, the brand name manufacturer’s aim is to delay the entry of generic competition;[185] yet, this practice is presumptively immunized by Noerr-Pennington. Importantly, the FDA must resolve citizen petitions within 180 days—a timeline intended to limit the dilatory effect of citizen petitions—though it does not always meet the deadline.[186] And although federal law allows the FDA to disregard blatantly dilatory petitions, in 2013, it had yet to do so.[187]

Noerr-Pennington broadly protects brand name manufacturers who attempt to forestall generic entry by filing citizen petitions. The sham exception only activates when the petition is objectively baseless. But this standard is elusive.

For example, in Louisiana Wholesale Drug Co. v. Sanofi-Aventis, the district judge instructed the jury that a citizen petition was not objectively baseless if “a reasonable pharmaceutical manufacturer could have realistically expected the FDA to grant [the] relief sought.”[188] Reviewing Sanofi-Aventis’ motion for judgment as a matter of law, the district court concluded that a reasonable jury could have found that the petition was not objectively baseless.[189] As this case illustrates, whether a petition is baseless will often be an inquiry purely decided by the factfinder.

Given the fact-intensive nature of citizen-petition sham analysis, a brand name manufacturer who files a citizen petition with a sound scientific basis is less likely to face antitrust liability.[190] On the flip side, if a citizen petition contains unsupported or faulty scientific evidence, the citizen petition is more likely to be found a sham.[191]

Another pivotal aspect of the sham analysis for citizen petitions centers on the second prong of the PRE test, which focuses on the defendant’s intent. Therefore, business documents discussing the citizen petition and the impetus for its submission will often be influential.[192]

Brand name manufacturers may also file patent infringement suits to challenge generic manufacturers that file Paragraph IV certifications. If the brand name manufacturer chooses to sue within 45 days, a 30-month stay halts the ANDA unless the patent expires or a court holds the patent invalid.[193] When faced with a patent infringement suit, some generic manufacturers respond with antitrust counterclaims. Presumably, the brand-name manufacturer’s lawsuit is immunized by Noerr-Pennington, but the PRE test still applies, determining whether the litigation falls within the sham exception.

Recently, the Third Circuit discussed the sham exception within the ANDA context, noting that, in some ways, it is more difficult to establish it in the ANDA context.[194] In FTC v. AbbVie, Inc., the court observed that Paragraph IV certifications are, by definition, infringing acts, thus a suit in response “could only be objectively baseless if no reasonable person could disagree with the assertions of noninfringement or invalidity in the certification.”[195] Further, the court recognized that the Hatch-Waxman Act deliberately incentivizes brand-name manufacturers to sue, thereby reducing the likelihood that serial lawsuits by brand-name manufacturers were brought with anticompetitive intent. In sum, the Hatch-Waxman Act creates a nuanced regulatory environment where Noerr-Pennington still applies but presents additional hurdles for antitrust plaintiffs seeking to overcome immunity.

Conclusion

Exemptions and immunities limit the reach of the antitrust laws. If the courts and agencies implement exemptions and immunities too expansively, anticompetitive conduct will elude enforcement and thereby injure consumers. The dynamic nature of the digital economy amplifies these concerns. Policymakers, courts, and regulators must diligently assess the ever-changing digital landscape and tailor antitrust doctrine accordingly.

Sectoral antitrust exemptions threaten competition and consumer welfare regardless of the industry. High-tech firms in the digital market continue to rent-seek in favor of antitrust exemptions. But economic and historical evidence proves that vigorous competition in the digital economy cannot be maintained if certain players receive antitrust immunity.

Digital markets attract the attention of both federal and state governments, contributing to tension within the federal structure. Enforcers at both levels are actively regulating private conduct in the digital space, often implicating antitrust and free speech concerns.

Careful examination of these issues will be vital to the preservation of consumer welfare and simultaneous preservation of core American values, including federalism, free speech, and the right to petition.

Footnotes

* We thank Rachel Burke and Ethan Hoffman for research assistance.

[1] United States v. Topco Assoc., 405 U.S. 596 (1972) (“Antitrust laws in general, and the Sherman Act in particular, are the Magna Carta of free enterprises.”).

[2] See also Northern Pac. Ry. Co. v. United States, 356 U.S. 1,4 (1956) (“The Sherman Act was designed to be a comprehensive charter of economic liberty aimed at preserving free and unfettered competition as a rule of trade.”); United States v. Socony Vacuum Oil Co., 310 U.S. 221 (1940) (characterizing the Sherman Act as a “charter of freedom”); Appalachian Coals, Inc. v. United States, 288 U.S. 344, 359 1933 (same).

[3] Implied immunity from antitrust scrutiny, inferred from the comprehensive nature of a specific regulatory regime, is discussed in Bruce H. Kobayashi & Joshua D. Wright, Antitrust and Ex-Ante Sector Regulation, in The GAI Report on the Digital Economy (2020). See, e.g., Bruce H. Kobayashi & Joshua D. Wright, Federalism, Substantive Preemption, and Limits on Antitrust: An Application to Patent Holdup, 5 J. Competition L. & Econ. 469 (2009); Bruce H. Kobayashi & Joshua D. Wright, The Limits of Antitrust and Patent Holdup: A Reply to Cary et al., 78 Antitrust L.J. 701, 717 (2012).

[4] Antitrust Modernization Commission, Report and Recommendation 350 (2007) [hereinafter AMC].

[5] Preserving Our Hometown Independent Pharmacies Act of 2011: Hearing on H.R. 1946 Before the Subcomm. on Intellectual Property, Competition, And the Internet of the H. Comm. On the Judiciary, 112th Cong. 24 (2012) (written testimony of Joshua D. Wright).

[6] Report on the State Action Task Force, Fed. Trade Comm’n (Sept. 2003) (recommends “clarification and re-affirmation of the original purpose of the state action doctrine”); Aaron S. Edlin and Rebecca Haw Allensworth, Cartels by Another Name: Should Licensed Occupations Face Antitrust Scrutiny? 162 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1093 (2014); Frank H. Easterbrook, Antitrust and the Economics of Federalism, 26 J. L. & Econ. 23, 24 (1983)

[7] Id.

[8] Parker v. Brown, 317 U.S. 341 (1943). See also N.C. State Bd. of Dental Examiners v FTC, 135 S.Ct. 1101 (2015); FTC v. Ticor Title Ins. Co., 504 U. S. 621 (1992); Rice v. Norman, 458 U.S. 654 (1982); Cal. Retail Liquor Dealers Ass’n. v. Midcal Aluminum, Inc., 445 U.S. 97 (1980); New Motor Vehicle Bd. of Cal. v. Orrin W. Fox Co., 439 U.S. 96 (1978); Exxon Corp. v. Governor of Md., 437 U.S. 117 (1978).

[9] See, e.g., Exec. Order No. 13,925, 85 Fed. Reg. 34,079 (May 28, 2020) (Executive Order on Preventing Online Censorship); Hearing on Fostering a Healthier Internet to Protect Consumers Before the Subcomm. on Comm. & Tech. and the Subcomm. on Consumer Prot. & Commerce of the H. Comm. on Energy & Commerce, 116th Cong. (2019); William P. Barr, Attorney General, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Remarks at the DOJ Workshop on Section 230: Nurturing Innovation or Fostering Unaccountability? (Feb. 19, 2020).

[10] See Berin Szóka & Ashkhen Kazaryan, Section 230: An Introduction for Antitrust and Consumer Protection Practitioners, in The GAI Report on the Digital Economy (2020).

[11] See NCAA v. Bd. of Regents, 468 U.S. 85, 107 (1984).

[12] AMC supra note 4, at 350.

[13] Preserving Our Hometown Independent Pharmacies Act of 2011: Hearing on H.R. 1946 Before the Subcomm. on Intellectual Property, Competition, and the Internet of the H. Comm. On the Judiciary, 112th Cong. 24 (2012) (written testimony of Joshua D. Wright).

[14] The Antitrust Modernization Commission (“AMC”) held for thirty-two statutory antitrust immunities that they were “skeptical about the value and basis for many, if not most or all, of these immunities.” AMC supra note 4, at 334-35.

[15] 49 U.S.C. § 10706.

[16] 15 U.S.C. § 1013.

[17] 46 U.S.C. § 40103.

[18] 7 U.S.C. §§ 291-92.

[19] 15 U.S.C. § 13(c).

[20] 15 U.S.C. § 45(a)(2); Investigation into the State of Competition in the Digital Marketplace: Before the Subcomm. On Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 116th Cong. 36 (2020). (written statement of James C. Cooper, Joshua D. Wright & John M. Yun) (arguing that Congress should eliminate the FTC Act’s exemptions for non-profits and common carriers as it creates ad hoc divisions of industries between the agencies and may potentially exclude the FTC from policing sectors of the internet, particularly as firms become increasingly vertically integrated.).

[21] Id.

[22] Id.

[23] George J. Stigler, The Theory of Economic Regulation, Bell J. Econ. & Management Sci. (1971) (“Because regulations such as antitrust exemptions are shaped by industries with strong political and financial influence, the exemption may exacerbate the market failures it sought to correct.”).

[24] See generally Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action: Public Good and the Theory of Groups (1971).

[25] John Roberti, Kelse Moen, & Jana Steenholdt, The Role and Relevance of Exemptions and Immunities in U.S. Antitrust Law, presented at United States Department of Justice Roundtable on Exemptions and Immunities from Antitrust Law (Mar.14, 2018), at 4. https://www.justice.gov/atr/roundtable-exemptions-and-immunities-antitrust-laws-wednesday-march-14-2018. (“The corresponding ‘stickiness’ of these exemptions is evidenced by the fact that many of the existing exemptions were passed nearly a hundred years ago and still exist today, even after economic theory has moved away from the theoretical foundations on which they were originally built.”).

[26] Id. at 11 (“However well-intentioned antitrust exemptions may be, most of them threaten to institutionalize anticompetitive conduct, often in sweeping ways that could be better addressed through more narrowly-tailored reforms that do not otherwise conflict with the modern, procompetitive thrust of the antitrust laws.”).

[27] Makan Delrahim, Assistant Attorney Gen., Antitrust Div., U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Opening Remarks at U.S. Dep’t of Justice Roundtable Discussion Series on Competition & Deregulation (Mar. 14, 2018), at 5, https://www.justice.gov/atr/page/file/1120641/download; see also Alden F. Abbott, Gen. Counsel, Fed. Trade Comm’n, Statement at AMC Statutory Immunities and Exemptions Hearing (Dec. 1, 2005), at 1–2 (“[V]igorous competition, protected by the antitrust laws, does the best job of promoting consumer welfare and a vibrant, growing economy.”).

[28] Cont’l T. V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc., 433 U.S. 36 (1977); see also California Dental Ass’n v. FTC, 526 U.S. 756 (1999); State Oil v. Kahn, 522 U.S. 3 (1997).

[29] Roberti, Moen, & Steenholdt, supra note 25, at 1. The most common example of a procompetitive restraint is a sports league, or otherwise an industry where the restraint is necessary to the very existence of the product or service. See e.g., Bd of Regents, 468 U.S. at 85; Broadcast Music, Inc. v. Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc., 441 U.S. 1 (1979).

[30] Roberti, Moen, & Steenholdt, supra note 25, at 2. Such exemptions were created for railroads, insurance, ocean shippers, and agricultural. The economic theory backing these exemptions was the “benevolent cartel” theory, which held “that organizing industries into highly regulated cartels that would orient their collective industry decisions in light of the common good would be most beneficial to the national economy.” Id.

[31] Id.

[32] Delrahim, supra note 27, at 5 (“When regulation replaces antitrust enforcement, the regulations—and regulators—become stealthy and disruptive forces that can interfere with the competitive marketplace. And, like a boa constrictor, they can slowly, and painfully, squeeze competition from the free market.”).

[33] Payment Card Interchange Fees: An Economic Assessment, Congressional Research Services: Specialist in Financial Economics, 2 (2010) [hereinafter CRS Report].

[34] Stephen Cannon, Assessing the Need for Antitrust Immunity For Collective Merchant Negotiations With Electronic Payment Systems at ABA Section of Antitrust Law, 2010 Spring Meeting (Apr. 22, 2010), https://constantinecannon.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/scannonaba04222010art.pdf.

[35] Credit Card Fair Fee Act of 2009, S. 1212, 111th Cong. (2009) (“Grants limited antitrust immunity to such providers and merchants, as well as to those providers who jointly determine among themselves the proportionate division of paid access fees.”); Credit Card Fair Fee Act of 2009, H.R. 2695, 111th Cong. (2009). A similar bill was proposed by House of Representatives in 2008. Credit Card Fair Fee Act of 2009, H.R. 5546 (2008). Likewise, this provision allowed for negotiations between merchants and credit card companies for access rates and terms. The difference between the 2008 and 2009 versions is who would be responsible for overseeing the negotiations schedules. The 2008 bill originally assigned that task to the panel of three full-time electronic payment system judges, appointed by the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission Bureau of Competition. However, the 2009 version gave that responsibility instead to the U.S. Attorney General.

[36] Cannon, supra note 34.

[37] Ohio v. Am. Express Co., 138 S. Ct. 2274, 2280 (2018).

[38] Benjamin Klein, Andres V. Lerner, Kevin M. Murphy, and Lacey L. Plache, Competition in Two-Sided Markets: The Antitrust Economics of Payment Card Interchange Fees, 73 Antitrust L.J. 571, 576–77 (2006) (“it makes no economic sense to conclude that competition among merchants must be controlled because of these inter-retailer effects. These effects are the essence of the competitive process. If merchants could collude in their payment card acceptance decisions, interchange fees would no doubt be lower. Similarly, merchant spending on advertising, parking, or other customer services also would be lower if they could collude on the provision of these services. That does not make such collusion desirable. A regulatory solution that mimics such collusion on the part of merchants would be contrary to the goal of antitrust and, by preventing competitive balancing, would place open-loop payment card systems at a competitive disadvantage in the marketplace.”).

[39] CRS Report, supra note 33, at 6; see also U.S. Government Accounting Office, Credit Cards: Rising Interchange Fees Have Increased Costs For Merchants, But Options For Reducing Fees Pose Challenges 44-45 (2009), http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d1045.pdf.

[40] Todd J. Zywicki, The Economics of Payment Card Interchange Fees and The Limits Of Regulation 3 (ICLE Fin. Reg. Program, White Paper Series, 2010).

[41] Zywicki, supra note 40, at 30.

[42] Fumiko Hayash, Payment Card Interchange Fees and Merchant Service Charges – An International Comparison, 1-3 Lydian Payments Journal 8 (2010).

[43] Zywicki, supra note 40, at 2 (“the claim that interchange fees are ‘too high’ fails . . . because it arbitrarily defines the purported costs of electronic payment systems while simultaneously ignoring the costs of ‘legacy’ payment systems such as cash and checks, especially those costs that are borne by consumers and society generally (as opposed to merchants directly)”); see also Timothy J. Muris, Testimony before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary (Jul. 19, 2006), at 5, https://www.judiciary.senate.

gov/imo/media/doc/muris_testimony_07_19_06.pdf (“The agreements that are in place between card systems, merchants, and cardholders are consensual, not the product of force or fraud. It is hard to imagine how intervention in the form of price regulation could possibly improve matters.”).

[44] Zywicki, supra note 40, at 3; see Klein et al., supra note 38, at 590.

[45] Zywicki, supra note 40, at 30; see also Adam J. Levitin, Priceless? The Economic Costs of Credit Card Merchant Restraints, 55 UCLA L. Rev. 1321, 1331-32 (2008).

[46] Zywicki, supra note 40, at 30; see also Richard Schmalensee, Payment Systems and Interchange Fees, 50(2) J. Indus. Econ. 103, 105 (2002) (“The main economic role of the interchange fee is not to exploit the system’s market power; it is rather to shift costs between issuers and acquirers and thus to shift charges between merchants and consumers to enhance the value of the payment system as a whole to its owners.”).

[47] Klein et al., supra note 38, at 576.

[48] Id.; see also Muris, supra note 43, at 6 (”The role of interchange in providing benefits to consumers is crucial to understand. When interchange increases, cardholders benefit. Because of intense competition between the many banks that issue payment cards, “higher” interchange revenues to issuing banks result in increased benefits on payment cards, such as increased rewards and lower fees.”).

[49] Zywicki, supra note 40, at 45; See generally Robert Stillman et al., Regulatory Intervention In The Payment Card Industry By The Reserve Bank Of Australia: Analysis Of The Evidence, CRA International 29 (2008).

[50] Zywicki, supra note 40, at 46; see also Klein et al., supra note 38, at 614.

[51] Zywicki, supra note 40, at 49. Reserve Bank of Australia, Preliminary Conclusions of the 2007/08 Review 17 (Apr. 2008), https://www.rba.gov.au/payments-and-infrastructure/payments-system-regulation/past-regulatory-reviews/review-of-card-payment-systems-reforms/pdf/review-0708-pre-conclusions.pdf [hereinafter RBA Preliminary Conclusions].

[52] Zywicki, supra note 40, at 49.

[53] “In Australia, following the regulation, annual fees increased by an average of 22% on standard credit cards and annual fees for rewards cards increased by 47%-77%, costing consumers hundreds of millions of dollars in higher annual fees.” Zywicki, supra note 40, at 50; see also RBA Preliminary Conclusions, supra note 51.

[54] “Any artificial reduction in the interchange fee could have far-reaching and undesirable results.” Zywicki, supra note 40, at 52.

[55] Zywicki, supra note 40, at 53 (“At the end of the day, the implication that by direct price regulation or through indirect measures aimed at putting downward regulatory pressure on interchange fees, regulators can identify and mandate the socially-optimal interchange fee is deeply suspect.”).

[56] H.R. 2054, 116th Cong. (2019); S. 1700, 116th Cong. (2019).

[57] Id. at Sect. (b).

[58] Press Release, Sen. John Kennedy, Statement on the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act (Jun. 03, 2019), https://www.kennedy.senate.gov/public/2019/6/u-s-sens-kennedy-klobuchar-file-legislation-to-protect-newspapers-from-social-media-giants.

[59] Press Release, Sen. Amy Klobuchar, Statement on the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act (Jun. 03, 2019), https://www.kennedy.senate.gov/public/2019/6/u-s-sens-kennedy-klobuchar-file-legislation-to-protect-newspapers-from-social-media-giants.

[60] PwC, IAB Internet Advertising Revenue Report: 2019 Full Year Results, Interactive Advertising Bureau (May 2019).

[61] Maurice E. Stucke & Allen P. Grunes, Why More Antitrust Immunity for the Media Is A Bad Idea, 105 Nw. U. L. Rev. 1399, 1404 (2011).

[62] Id. The NPA was created because of the JOA made between two San Francisco newspapers—the Examiner and the San Francisco Chronicle.

[63] Id.

[64] Id.

[65] Id. at 1406.

[66] S. Comm. on the Judiciary, Subcomm. on Antitrust and Monopoly, 91 Cong., The Newspaper Preservation Act: Hearings, Ninety-First Congress, First Session, on S. 1520, Pursuant to S. Res. 40. June 12, 13 and 20, 1969 296 (U.S. Gov’t Print. Office, 1969) (testimony of Richard W. McLaren, Assistant Attorney Gen., Antitrust Div., U.S. Dep’t of Justice).

[67] See id. at 296-98.

[68] Stucke & Grunes, supra note 61, at 1406.

[69] Id.

[70] Leonard Downie, Jr., & Michael Schudson, The Reconstruction of American Journalism, Col. Journalism Rev. 28-29 (Oct. 19, 2009). See also Potential Policy Recommendations to Support the Reinvention of Journalism, Fed. Trade Comm’n, 13-14 (2010), https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/public

_events/how-will-journalism-survive-internet-age/new-staff-discussion.pdf (citing Grunes, Mar. 10, 2010 Tr. at 199 (noting that JOAs under the NPA “were a sort of Faustian bargain where the circulation and advertising functions could be combined, but the editorials and reportorial functions would be kept separate and would continue to compete”)). See also id. (citing Picard, Dec. 1, 2009 Tr. at 79-80 (noting that an antitrust exemption “will do substantial harm to consumers and advertisers”)).

[71] John M. Yun, News Media Cartels are Bad News for Consumers, CPI’s North American Column (2019).

[72] Id. at 4.

[73] Michael Mandel, The Declining Cost of Advertising: Policy Implications, Progressive Policy Institute 4 (Jul. 2010) (“Taken together, this implies that the shift from print to digital advertising is being driven in large part by the relative (low) price of digital advertising. We calculate, based on several assumptions, that for every $3 that an advertiser spends on digital advertising, they would have to spend $5 on print advertising to get the same impact. In the economic sense, digital advertising is more productive than print advertising. The benefits of these lower prices flow directly to advertisers and consumers.”).

[74] Id.

[75] Id.

[76] Id. at 14.

[77] Id.

[78] Parker, 317 U.S. at 341.

[79] See Hoover v. Ronwin, 466 U.S. 558, 568 (1984) (upheld grading scale for Arizona Bar admission created by the Committee on Examinations and Admissions under state action immunity); see also Bates v. State Bar of Ariz., 433 U.S. 350, 359 (1977) (the disciplinary ruling of the Arizona Bar committee was immune from antitrust liability under the state action doctrine; however, it was struck down for violating the First Amendment).

[80] See Press Release, FTC to Study Impact of COPAs (Oct. 21 2019), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2019/10/ftc-study-impact-copas (FTC announcing 6b study examining state Certificate of Public Advantage laws that allow states to immunize mergers and collaborations from antitrust scrutiny).

[81] Parker, 317 U.S. at 352.

[82] Id.; see also N.C. Dental, 135 S.Ct. at 1121-22; Ticor Title Ins. Co., 504 U. S. at 632; Rice, 458 U.S. at 659; Midcal, 445 U. S. at 105; New Motor Vehicle Bd. of Cal., 439 U.S. at 110-11; Exxon Corp., 437 U.S. at 133.

[83] Parker, 317 U.S. at 351; see also Midcal, 445 U.S. at 106 (the state cannot save a regulatory scheme from preemption by placing a “gauzy cloak of state involvement over what is essentially a private price-fixing arrangement.”).

[84] Rice, 458 U.S. at 661.

[85] N.C. Dental, 135 S.Ct. at 1121-22; Midcal, 445 U.S. at 105.

[86] James C. Cooper & William E. Kovacic, U.S. Convergence with International Competition Norms: Antitrust Law and Public Restraints on Competition, 90 Boston U. L. Rev. 1555 (2010).

[87] See id.; Easterbrook, supra note 6, at 24; Richard Squire, Antitrust and the Supremacy Clause, 59 Stan. L. Rev. 77, 119-20 (2006) (arguing that the state must incur “public costs” to supervise a price setting regime).

[88] See Easterbrook, supra note 6, at 33 (arguing that such an all or nothing choice would result in a net increase in regulatory costs).

[89] Timothy Brennan, Trinko v. Baxter: The Demise of U.S. v. AT&T, 50 Antitrust Bull. 635 (2006).

[90] Easterbrook, supra note 6, at 29–33.

[91] Id.; see also Bruce H. Kobayashi & Larry E. Ribstein, The Economics of Federalism (Univ. Ill. L. & Econ. Research Paper No. LE06-001, 2006).

[92] Easterbrook, supra note 6, at 29–33.

[93] 317 U.S. 341, 345 (1943).

[94] Id. at 310.

[95] See Tad Lipsky, Joshua D. Wright, Douglas H. Ginsburg, Bruce H. Kobayashi, and John M. Yun, U.S. Dep’t of Justice Antitrust Div. Public Roundtable Series on Competition and Deregulation, First Roundtable on State Action, Statutory Exemptions and Implied Immunities, Comment of the Global Antitrust Institute, Antonin Scalia Law School George Mason University (George Mason Law & Econ., Research Paper No. 18-03, 2018).

[96] Easterbrook, supra note 6, at 45–47.

[97] Id. at 46 (“[an antitrust] doctrine proscribing state regulation that had ‘excessive’ interstate effects might breed confusion without corresponding benefit”); see, e.g., Hughes v. Oklahoma, 441 U.S. 322, 336 (1979) (“the first step in analyzing any law subject to judicial scrutiny under the negative Commerce Clause is to determine whether it “regulates evenhandedly with only ‘incidental’ effects on interstate commerce, or discriminates against interstate commerce”).

[98] For a horizontal disagreement example, the Antitrust Division filed an amicus brief in the FTC’s case against Qualcomm, opposing the FTC’s legal position. Brief of the United States of America

as Amicus Curiae in Support of Appellant and Vacatur, FTC v. Qualcomm, Inc., No. 19-16122 (N.D. Cal. 2019).

[99] Makan Delrahim, Assistant Attorney Gen., Antitrust Div., U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Remarks Before The Media Institute: “Getting Better”: Progress and Remaining Challenges in Merger Review (Feb. 5, 2020), at 5, https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/file/1245056/download.

[100] Id. at 6.

[101] The Antitrust Division and FCC filed a brief opposing the relief requested by the states. Id. at 7.

[102] Id. at 6.

[103] Id.

[104] Id. at 9 (“[C]ourts should not award any private party, including the states, relief that is incompatible with relief secured by the federal government. . . . That would wreak havoc on parties’ ability to merge, on the government’s ability to settle cases, and cause real uncertainty in the market for mergers and acquisitions.”).

[105] Douglas H. Ginsburg & Joshua D. Wright, Antitrust Settlements: The Culture of Consent, in 1 William E. Kovacic: An Antitrust Tribute–Liber Amicorum 177, 183 (2012).

[106] Id.